Table of Contents

Introduction: When Narrative Style Becomes Your Shadow

Something strange happens when you read Virginia Woolf’s stream-of-consciousness prose versus Ernest Hemingway’s stark sentences. The words don’t just carry meaning—they rewire your inner voice. Your thoughts begin to flow differently, matching the rhythm of what you’re reading. This isn’t mere literary appreciation. It’s psychological transformation.

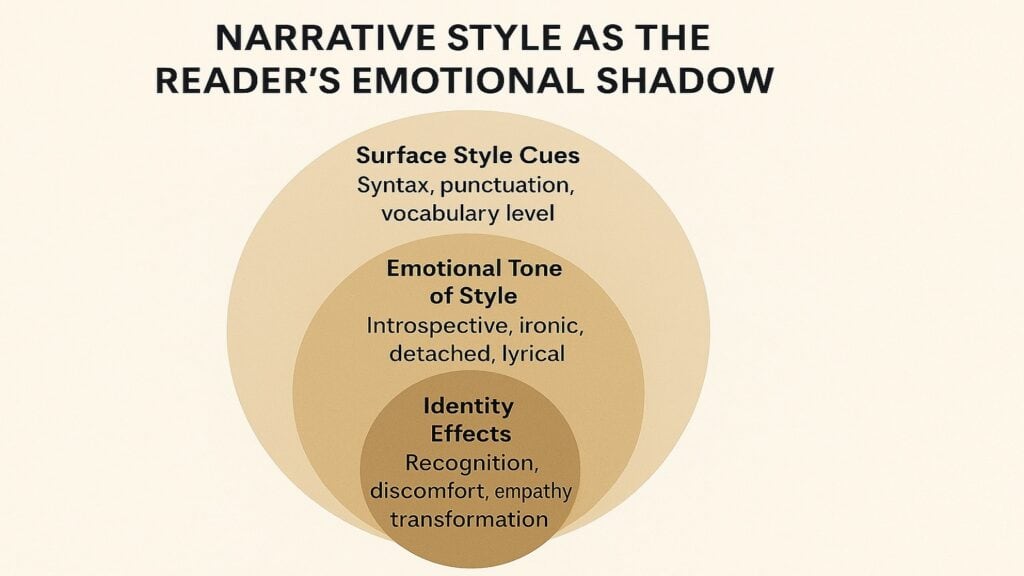

Narrative style operates like a shadow self that follows readers through every page. While plot delivers story events and characters provide emotional anchors, narrative style does something more intimate—it changes how readers experience being themselves while reading. The sentence structure becomes your breathing pattern. The tone becomes your emotional filter. The perspective becomes your temporary way of seeing the world.

This transformation happens below conscious awareness. When James Joyce fragments reality in Ulysses, readers don’t just witness Leopold Bloom’s consciousness—they temporarily adopt fragmented thinking patterns. When Toni Morrison weaves lyrical passages in Beloved, readers don’t just read about memory—they experience remembering differently. The narrative style becomes a psychological role that readers inhabit.

The six ways narrative style alters reader identity reveal literature’s hidden power. First, narrative style acts as an emotional immersion engine, pulling readers into feeling states that override daily perceptions. Second, different perspectives create mirror effects that shift readers’ points of reference. Third, narrative style functions as an identity simulator where readers become co-creators of the self they’re reading into existence. Long, flowing sentences slow breathing and induce meditative states. Fifth, narrative style transforms readers into performers wearing the text’s internal voice. Finally, modern storytelling techniques create reader avatars that reflect suppressed aspects of personal identity.

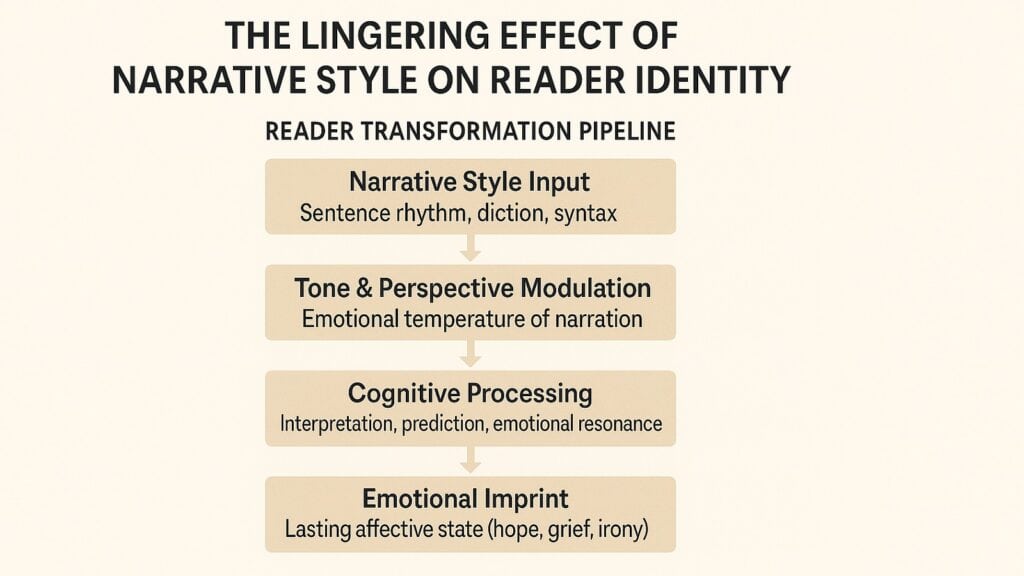

Understanding these mechanisms reveals why certain books linger in consciousness long after reading ends. The narrative style leaves psychological afterimages that subtly reshape how readers think, feel, and perceive reality in their daily lives.

Table 1: Narrative Style Categories and Their Psychological Impact

| Style Category | Primary Effect | Example Authors | Reader Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stream-of-consciousness | Fragments linear thinking | Joyce, Woolf | Internal monologue mimics text flow |

| Minimalist prose | Strips emotional excess | Hemingway, Carver | Reader fills emotional gaps |

| Lyrical narrative | Heightens sensory awareness | Morrison, Ondaatje | Enhanced perception of beauty |

| Epistolary format | Creates intimate confession | Richardson, Walker | Reader becomes confidant |

| Second-person address | Forces self-identification | Calvino, Oates | Reader cannot maintain distance |

| Fragmented structure | Disrupts temporal flow | Vonnegut, Atwood | Non-linear memory processing |

1. Narrative Style as Emotional Immersion Engine

Affect Theory in literary studies reveals something crucial about how readers encounter texts. Rather than simply interpreting meaning, readers experience visceral responses that bypass rational analysis. Narrative style serves as the primary vehicle for these pre-cognitive emotional states. The rhythm of sentences, the texture of language, and the pace of revelation create feeling states that readers inhabit while reading.

Consider how different narrative styles manufacture distinct emotional atmospheres. Cormac McCarthy’s run-on sentences in Blood Meridian create breathless urgency that mirrors violence and chaos. Readers find themselves psychologically overwhelmed, matching the protagonists’ disorientation. Meanwhile, Jane Austen’s balanced clauses and ironic observations in Pride and Prejudice cultivate emotional restraint and social awareness. Readers adopt her measured perspective on human folly.

This emotional calibration happens through what affect theorists call “intensity transfer.” The narrative style doesn’t just describe emotions—it generates them in readers’ bodies. Stream-of-consciousness passages make readers feel mentally scattered. Staccato dialogue creates tension in readers’ muscles. Lyrical descriptions slow readers’ internal pace and heighten aesthetic sensitivity.

The psychological mechanism operates through rhythmic entrainment. Just as musicians sync to the same beat, readers’ nervous systems sync to narrative rhythms. Short, punchy sentences accelerate heart rate and create alertness. Long, continuous sentences promote slower breathing and facilitate meditative states. This physiological synchronization explains why certain books feel energizing while others feel calming.

Narrative style also creates what researchers call “emotional contagion”—the automatic mimicking of emotional states. When a first-person narrator expresses anxiety through fragmented thoughts and incomplete sentences, readers begin experiencing similar mental patterns. The style becomes a emotional costume that readers wear throughout the reading experience.

Table 2: Affect Theory Applications in Narrative Style

| Emotional State | Narrative Technique | Literary Example | Reader’s Physical Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Fragmented sentences, interruptions | Sylvia Plath’s journals | Increased heart rate, shallow breathing |

| Melancholy | Extended metaphors, slow pace | Virginia Woolf’s passages | Lowered energy, contemplative mood |

| Excitement | Short sentences, active voice | Action thriller prose | Muscle tension, alertness |

| Confusion | Non-linear structure, multiple voices | David Foster Wallace | Mental fatigue, disorientation |

| Serenity | Balanced clauses, natural imagery | Nature writing style | Relaxed breathing, calm focus |

| Urgency | Run-on sentences, minimal punctuation | Beat poetry influence | Rapid reading pace, restlessness |

2. Narrative Style and the Mirror Effect of Perspective

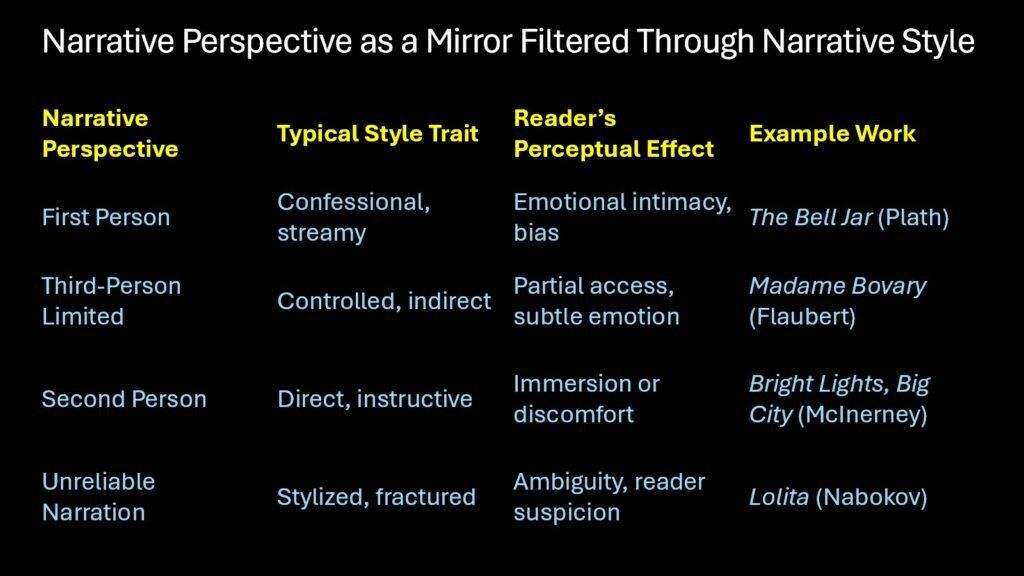

Perspective in narrative functions like a psychological lens that determines not just what readers see, but how they process reality while reading. First-person narration creates intimate identification, while third-person omniscient offers godlike detachment. Second-person narration forces readers into uncomfortable self-recognition. Each perspective shift requires readers to adopt different cognitive and emotional positions.

The mirror effect occurs when readers unconsciously align their mental processes with the narrator’s point of view. Reading Holden Caulfield’s first-person complaints in The Catcher in the Rye makes readers temporarily adopt adolescent cynicism and linguistic patterns. Even adult readers find themselves thinking in Holden’s voice, using his judgmental observations and slang expressions. The perspective becomes a mental costume that persists beyond reading sessions.

Close third-person narration creates what psychologists call “theory of mind extension.” Readers must constantly interpret a character’s thoughts and motivations while maintaining awareness that these aren’t their own thoughts. This cognitive juggling act strengthens empathetic abilities and perspective-taking skills. Studies show that readers of literary fiction score higher on empathy tests than readers of popular fiction, partly due to complex narrative perspectives.

Multiple perspective narratives, like those in Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad, require readers to mentally shift between different character viewpoints within single reading sessions. This perspective switching exercises cognitive flexibility and challenges readers’ assumptions about truth and reliability. Each character’s narrative style reflects their personality, education, and emotional state, forcing readers to code-switch between different mental modes.

Unreliable narrators create the most dramatic perspective effects. When readers gradually realize the narrator cannot be trusted, they must reconstruct events while maintaining dual awareness—the narrator’s version and the implied reality. This creates what literary scholars call “interpretive anxiety,” where readers become hypervigilant about textual clues and hidden meanings.

Table 3: Narrative Perspectives and Cognitive Effects

| Perspective Type | Mental Process Required | Identity Impact | Example Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-person intimate | Direct identification | Strong emotional merger | Internal monologue mimicry |

| Third-person limited | Selective empathy | Controlled emotional distance | Character-filtered observations |

| Third-person omniscient | Multiple viewpoint tracking | Expanded moral perspective | God-like awareness |

| Second-person address | Forced self-recognition | Uncomfortable self-examination | Direct reader confrontation |

| Multiple perspectives | Cognitive flexibility exercise | Relativistic worldview | Character voice switching |

| Unreliable narration | Interpretive detective work | Skeptical reading habits | Hidden truth discovery |

3. Narrative Style as an Identity Simulator

Louise Rosenblatt’s Reader-Response Theory reveals that meaning emerges from the transaction between reader and text, not from the text alone. Narrative style becomes the interface for this transaction, requiring readers to actively construct meaning and, in the process, construct temporary versions of themselves. Different narrative styles demand different types of reader participation, creating various identity simulations.

Stream-of-consciousness narratives require readers to become mental detectives, piecing together fragmented thoughts into coherent experiences. When reading Molly Bloom’s famous soliloquy in Ulysses, readers must supply logical connections that Joyce deliberately omitted. This cognitive work creates a collaborative identity between reader and character—readers become co-creators of Molly’s consciousness while temporarily adopting her associative thinking patterns.

Experimental narratives push this collaboration further. Mark Danielewski’s House of Leaves uses typography, page layout, and formatting to force readers into physical interaction with the text. Readers must turn pages sideways, read backwards, and decode visual puzzles. This physical engagement creates embodied reading experiences where readers become performers in the narrative’s experimental structure.

Epistolary narratives create intimate confession dynamics. Reading Alice Walker’s The Color Purple through Celie’s letters transforms readers into confidants and witnesses. The direct address format makes readers complicit in the character’s emotional journey. Readers cannot maintain neutral distance—they become the implied recipient of the character’s most private thoughts.

Contemporary autofiction blurs boundaries between author, narrator, and reader identities. Writers like Rachel Cusk and Karl Ove Knausgård create narrative styles so transparent they seem to offer direct access to consciousness. Readers experience the uncanny sensation of thinking someone else’s actual thoughts, creating identity confusion that persists after reading ends.

Table 4: Reader-Response Theory in Practice

| Narrative Style | Reader Participation Level | Identity Construction Process | Collaborative Element |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stream-of-consciousness | High cognitive reconstruction | Mental gap-filling | Thought pattern mimicry |

| Experimental typography | Physical page interaction | Embodied meaning-making | Performance reading |

| Epistolary format | Emotional witnessing | Confidant role-playing | Intimate confession receipt |

| Autofiction transparency | Psychological merger | Direct consciousness access | Author-reader identity blur |

| Fragmented narrative | Interpretive puzzle-solving | Story reconstruction | Creative completion |

| Interactive fiction | Decision-making participation | Character choice simulation | Narrative co-creation |

4. Narrative Style and the Collapse of Temporal Identity

Linear time provides the foundation for personal identity—we understand ourselves through chronological life narratives that connect past, present, and future selves. When narrative styles disrupt temporal flow, they challenge readers’ normal identity construction processes. Non-linear narratives, looping flashbacks, and fractured timelines pull readers out of their familiar temporal experience, creating identity displacement.

Kurt Vonnegut’s “unstuck in time” technique in Slaughterhouse-Five doesn’t just describe Billy Pilgrim’s temporal displacement—it recreates the experience for readers. The narrative jumps between past, present, and future without transition signals, forcing readers to abandon chronological expectations. This temporal confusion mirrors trauma’s effect on memory and time perception, allowing readers to experience psychological fragmentation firsthand.

Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad uses multiple time periods and narrative styles to show how identity shifts across decades. Each chapter employs different temporal techniques—some move forward, others backward, one uses PowerPoint slides to show future events. Readers must constantly reorient themselves temporally while tracking character development across non-sequential chapters. This temporal exercise reveals how identity remains fluid rather than fixed.

Circular narratives, like those in Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, create eternal return experiences where events repeat across generations. Readers experience the uncanny sensation of déjà vu as character names, situations, and outcomes echo previous chapters. This cyclical framework contests the Western notion of linear time and momentarily reshapes the readers’ perception of causality and consequence.

Memory-based narratives employ associative rather than chronological organization. Proust’s In Search of Lost Time illustrates the genuine operation of memory—spontaneous stimuli that compress temporal gaps and render past events strikingly clear in current awareness. Readers must follow memory’s logic rather than clock time, temporarily adopting non-linear thinking patterns that persist beyond reading sessions.

Table 5: Temporal Narrative Techniques and Identity Effects

| Temporal Technique | Time Experience | Identity Impact | Psychological Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-linear jumping | Fragmented chronology | Destabilized self-concept | Trauma-like disorientation |

| Circular repetition | Eternal return sensation | Cyclical identity patterns | Fatalistic worldview adoption |

| Memory association | Dream-like time flow | Fluid past-present merger | Enhanced memory sensitivity |

| Future retrospective | Predetermined awareness | Fixed destiny feeling | Reduced agency perception |

| Multiple timelines | Simultaneous realities | Parallel self-concepts | Expanded possibility thinking |

| Temporal loops | Recursive experience | Repetitive identity patterns | Obsessive-compulsive mimicry |

5. Narrative Style as a Role-Playing Device

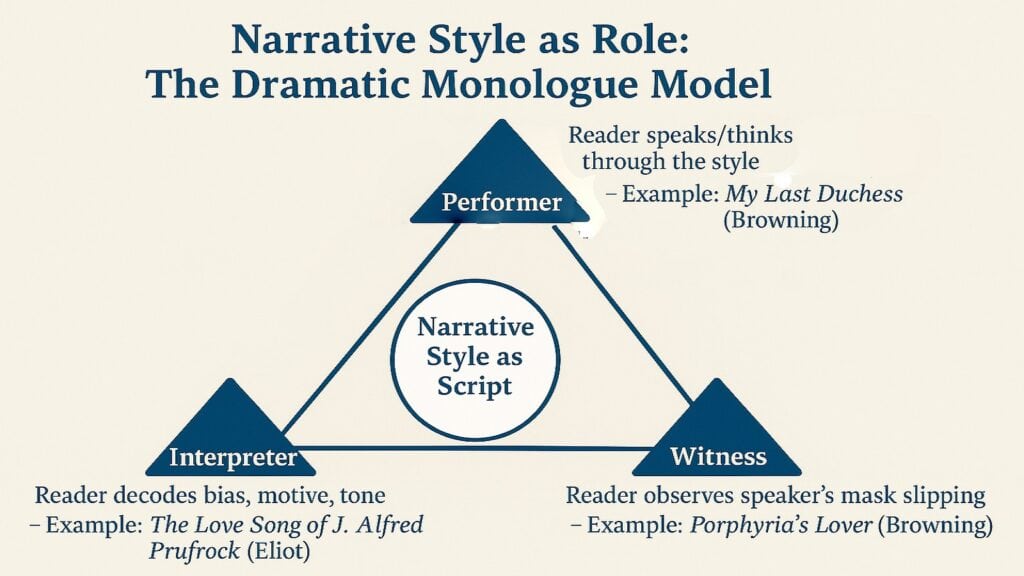

The dramatic monologue tradition established by poets like Robert Browning created literary voices designed for performance. Contemporary narrative styles continue this tradition, transforming readers into performers who must embody the text’s internal voice. Each narrative style requires readers to adopt specific vocal patterns, emotional registers, and personality traits while reading.

Confessional narratives demand intimate, whispered delivery. Reading Sylvia Plath’s autobiographical fiction requires readers to adopt her intense, self-examining voice. The narrative style becomes a psychological costume that readers wear—confessional, analytical, and emotionally raw. Readers find themselves thinking in Plath’s confessional mode, examining their own experiences with similar psychological intensity.

Ironic narratives require readers to maintain dual awareness—the surface meaning and the implied criticism. Jane Austen’s free indirect discourse forces readers to simultaneously inhabit characters’ thoughts while recognizing the author’s satirical distance. This cognitive split creates sophisticated reading positions where readers become both participant and critic, adopting Austen’s wry observational stance.

Vernacular narratives demand linguistic shape-shifting. Reading Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God requires readers to internalize dialect patterns and cultural expressions foreign to mainstream English. The narrative style becomes a cultural costume that temporarily relocates readers into different linguistic and social communities.

Stream-of-consciousness narratives transform readers into method actors who must access unconscious mental processes. Reading Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway necessitates that readers engage with associative thought processes, unpredictable memory prompts, and emotional shifts that reflect true consciousness. This psychological mimicry exercises readers’ introspective abilities and enhances self-awareness.

Table 6: Dramatic Monologue Elements in Modern Narrative

| Narrative Voice Type | Performance Requirement | Reader Transformation | Psychological Costume |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confessional intensity | Intimate self-examination | Enhanced introspection | Therapeutic vulnerability |

| Ironic sophistication | Dual awareness maintenance | Critical distance development | Satirical perspective |

| Vernacular authenticity | Dialect internalization | Cultural code-switching | Community membership |

| Stream-of-consciousness | Associative thinking mimicry | Unconscious access | Psychological method acting |

| Grandiose rhetoric | Elevated speech patterns | Heroic self-concept | Epic personality adoption |

| Minimalist restraint | Emotional understatement | Stoic behavior modeling | Hemingway-esque detachment |

6. Narrative Style and the Formation of Reader Avatars

Contemporary narrative styles increasingly blur boundaries between reader and character, creating what can be called “reader avatars”—temporary identity constructs that combine reader psychology with character traits. These avatars reflect suppressed or aspirational aspects of readers’ actual identities, allowing safe exploration of alternative selves through narrative immersion.

Autofictional narratives create the strongest avatar effects. Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy uses a nearly transparent narrator who serves as a vessel for other characters’ stories. Readers project themselves into this empty narrator space, creating avatars that combine their own consciousness with the fictional situations they encounter. The narrator becomes a reader avatar exploring alternative life possibilities.

Fragmentary narratives require readers to construct coherent identities from scattered pieces. Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation presents motherhood and marriage through disconnected observations and fragments. Readers must supply emotional connections between fragments, creating avatars that blend their own relationship experiences with the narrator’s situation. The collaborative construction creates deeply personal reading experiences.

Second-person narratives force avatar creation through direct address. Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler directly addresses “you” throughout, making readers simultaneous characters in the narrative. This technique prevents readers from maintaining comfortable distance—they must inhabit the “you” being addressed, creating avatars that combine their actual selves with fictional circumstances.

Hybrid narratives mixing genres, formats, and voices require readers to develop flexible avatar identities. Claudia Rankine’s Citizen combines poetry, prose, visual art, and essay forms to explore racial microaggressions. Readers must shift between different reading modes and emotional registers, creating complex avatars capable of processing multiple forms of representation simultaneously.

Table 7: Reader Avatar Formation Techniques

| Narrative Technique | Avatar Construction Method | Reader Psychology Accessed | Identity Exploration Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transparent narrator | Projection vessel | Suppressed desires | Alternative life paths |

| Fragmented identity | Collaborative completion | Personal memory patterns | Relationship dynamics |

| Second-person address | Forced self-insertion | Social role flexibility | Behavioral possibilities |

| Hybrid form mixing | Multiple mode adaptation | Cognitive versatility | Representational literacy |

| Unreliable confession | Truth reconstruction work | Moral judgment patterns | Ethical decision-making |

| Cultural code-switching | Community membership testing | Identity adaptability | Social belonging exploration |

Conclusion: When the Book Ends, But the Self Remains Altered

The book closes, but something lingers. Readers discover their internal voice has shifted slightly, carrying traces of the narrative style they just inhabited. A Virginia Woolf reader might find their thoughts flowing more associatively. A Hemingway reader might notice their inner commentary becoming more spare and direct. These psychological afterimages reveal narrative style’s hidden power to reshape consciousness.

Research in cognitive psychology supports what readers intuitively experience—extended exposure to different linguistic patterns creates lasting neural changes. Reading complex literary fiction strengthens cognitive flexibility, empathy, and abstract reasoning abilities. More specifically, different narrative styles exercise different cognitive muscles, leaving readers with enhanced mental capacities that persist beyond individual reading sessions.

The six ways narrative style alters reader identity work together to create comprehensive psychological transformations. Emotional immersion engines calibrate feeling states. Mirror perspectives shift cognitive positions. Identity simulators require collaborative construction. Temporal collapses disrupt normal time experience. Role-playing devices demand performance. Avatar formation enables identity exploration. Together, these mechanisms explain why serious readers often report feeling changed by transformative books.

This transformation process has broader implications for education, therapy, and personal development. Understanding how narrative styles create identity effects could inform reading curricula designed to develop specific cognitive abilities. Therapeutic applications might use particular narrative styles to help patients explore alternative self-concepts safely. Personal reading choices become more intentional when readers understand how different styles will affect their psychological development.

The digital age intensifies these effects through increased reading exposure across multiple platforms and formats. Social media narrative styles—fragmentary, immediate, emotionally charged—train readers in particular psychological patterns. Understanding narrative style’s identity effects becomes crucial for maintaining cognitive diversity in an increasingly homogenized information environment.

Perhaps most significantly, recognizing narrative style’s psychological power reveals reading as fundamentally creative act. Readers don’t just consume stories—they collaboratively construct temporary selves through linguistic interaction. Every reading experience becomes a small experiment in alternative identity, a chance to try on different ways of thinking, feeling, and being human.

Table 8: Long-term Effects of Narrative Style Exposure

| Style Category | Cognitive Enhancement | Emotional Development | Identity Flexibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Literary complexity | Abstract reasoning improvement | Emotional intelligence growth | Perspective-taking ability |

| Experimental forms | Creative problem-solving | Ambiguity tolerance | Adaptive thinking patterns |

| Cultural narratives | Cross-cultural competence | Empathy expansion | Social identity flexibility |

| Historical perspectives | Temporal thinking skills | Historical empathy | Chronological identity sense |

| Philosophical styles | Critical thinking enhancement | Ethical reasoning development | Value system examination |

| Psychological realism | Self-awareness improvement | Emotional regulation skills | Introspective capacity |

The shadow self that follows readers through narrative experiences never fully disappears. It accumulates across reading lifetimes, creating the complex, multifaceted identities that distinguish serious readers. In the end, we become composites of all the narrative styles we’ve inhabited, walking libraries of psychological possibilities that narrative artists helped us discover within ourselves.