Table of Contents

Introduction: When Narrative Emotion Walks Into the Room

Something shifts when narrative emotion enters a story. The air thickens, characters breathe differently, and readers sense a presence they cannot name. Unlike the emotions characters feel, narrative emotion becomes a force that shapes everything around it. It moves through scenes like smoke, altering the weight of dialogue and the texture of silence.

Think of Lady Macbeth’s guilt in Shakespeare’s tragedy. Her emotional torment doesn’t simply exist within her—it seeps into the castle walls, transforms the meaning of blood, and changes how we read every shadow. This is narrative emotion at work, functioning as an invisible architect that builds the story’s emotional landscape.

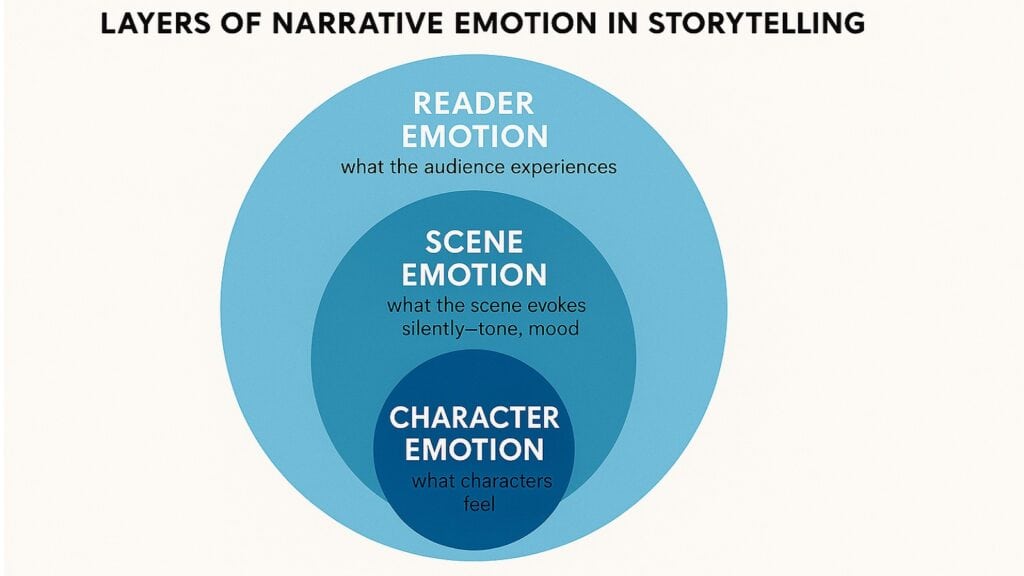

Narrative emotion operates differently from character emotion. While characters experience feelings, narrative emotion creates the conditions under which those feelings matter. It establishes the emotional rules of a fictional world, determining which feelings carry weight and which fade into background noise. When grief enters a scene in Toni Morrison’s Beloved, it doesn’t just affect the characters—it reshapes the very fabric of memory and time within the narrative.

Writers have long understood this distinction, though they rarely name it directly. Virginia Woolf spoke of the “cotton wool” of everyday experience that conceals deeper emotional truths. James Baldwin wrote about the blues as a form that doesn’t just express pain but creates a space where pain can be transformed into art. These insights point toward narrative emotion’s unique power to create meaning through feeling.

The six ways narrative emotion shapes stories reveal a deeper truth about how fiction works. Stories don’t simply contain emotions—they become emotional experiences that outlast the reading. They create emotional memories that feel as real as our own lived experiences, sometimes more real.

| Narrative Emotion Functions | Traditional Character Emotion | Impact on Story Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Creates atmospheric conditions | Exists within individual characters | Shapes overall narrative architecture |

| Influences reader interpretation | Drives character actions | Determines story’s emotional logic |

| Persists across scenes | Fluctuates with plot events | Establishes consistent emotional world |

| Operates as story element | Serves character development | Functions as invisible storytelling tool |

1. Narrative Emotion as the Unspoken Guest in the Scene

Reader-Response Theory teaches us that meaning emerges from the dance between text and reader. When narrative emotion enters a scene, it creates what Wolfgang Iser called “gaps” that readers must fill with their own emotional understanding. The emotion doesn’t announce itself—it arrives quietly, shaping how we interpret every gesture and word.

Consider the opening of Raymond Carver’s “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.” The story begins with four friends drinking gin and talking about love, but something else sits at the table with them. A kind of desperate longing permeates the scene, not through explicit statement but through the rhythm of conversation, the way characters avoid certain topics, and the accumulating weight of things left unsaid.

This unspoken emotional presence works through what reader-response theorists call “implied meaning.” Readers sense what characters cannot or will not acknowledge. The narrative emotion of unresolved grief in Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking operates this way—it shapes every observation about everyday life, making ordinary moments carry extraordinary emotional weight.

The power of narrative emotion as an unspoken guest lies in its ability to create shared understanding between author and reader without explicit communication. When Alice Munro writes about the aftermath of betrayal in her short stories, the emotion of violated trust doesn’t need to be named. It saturates the descriptions of familiar places that now feel strange, the way characters move through spaces they once knew intimately.

This emotional presence requires active reader participation. We bring our own experiences of longing, loss, or joy to fill the emotional spaces the narrative creates. The story provides the architecture, but readers construct the emotional reality within that framework. This collaboration between text and reader creates the unique intimacy of literary experience.

The technique works because emotions are fundamentally relational. We recognize emotional atmospheres even when we cannot name them precisely. A scene carries the weight of suppressed anger not through dramatic outbursts but through the careful politeness of characters who refuse to acknowledge their fury.

| Reader-Response Elements | How Narrative Emotion Operates | Reader’s Role |

|---|---|---|

| Textual gaps | Creates emotional spaces for interpretation | Fills gaps with personal emotional knowledge |

| Implied meaning | Suggests rather than states emotional truth | Recognizes unspoken emotional content |

| Active interpretation | Invites emotional participation | Collaborates in creating story’s emotional reality |

| Subjective response | Allows multiple emotional readings | Brings individual emotional experience to narrative |

2. Narrative Emotion and the Architecture of Conflict

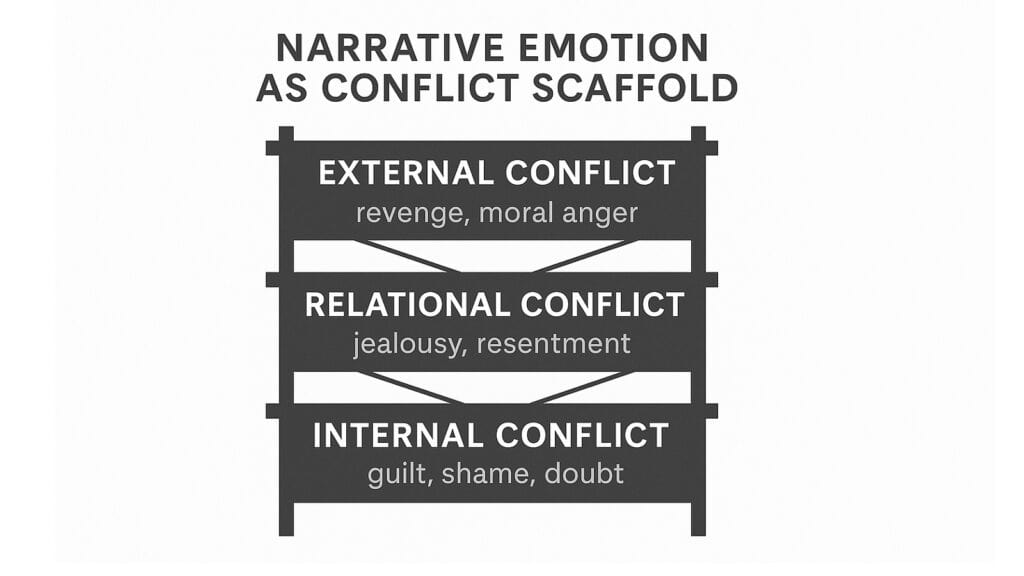

Narrative emotion builds the scaffolding of story conflict in ways that mechanical plot devices cannot. When jealousy operates as narrative emotion rather than simple character trait, it becomes a structural force that shapes every interaction, determines what characters notice, and influences which details the story reveals or conceals.

In Shakespeare’s Othello, jealousy serves not only as Othello’s tragic flaw but also as the central organizing principle of the narrative. The emotion restructures reality within the play’s world, making innocuous gestures appear suspicious and transforming love tokens into evidence of betrayal. The narrative doesn’t simply show us a jealous character; it creates a jealous world where normal social interactions become dangerous.

This architectural function of narrative emotion appears clearly in domestic fiction. In Richard Yates’ Revolutionary Road, the narrative emotion of disappointed expectations shapes how Frank and April Wheeler interpret each other’s words and actions. Their conversations occur within an emotional atmosphere where every attempt at connection becomes another confirmation of their fundamental incompatibility.

The emotion operates like a lens that filters all story information. When shame functions as narrative emotion in novels like James Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain, it doesn’t simply affect individual characters—it determines which memories surface, which conversations become possible, and which truths remain buried. The story’s structure reflects the emotion’s logic rather than chronological logic.

This architectural approach to emotion creates more complex conflicts than external obstacles alone. Internal emotional pressures generate plot movement through the accumulation of small moments rather than dramatic confrontations. Characters make decisions based on emotional atmospheres they cannot fully understand, leading to consequences that feel both inevitable and surprising.

The technique allows writers to explore how emotions shape perception and choice. When guilt operates as narrative emotion, characters interpret neutral events as judgment, avoid certain places or people, and make decisions designed to manage their emotional discomfort rather than achieve their stated goals.

| Conflict Type | Emotional Architecture | Story Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Internal tension | Emotions shape character perception | Creates psychological complexity |

| Relationship dynamics | Emotional atmosphere influences interaction | Determines communication patterns |

| Decision-making pressure | Emotions provide motivation beyond logic | Drives plot through emotional necessity |

| Environmental conflict | Emotions infuse settings with meaning | Makes locations emotionally charged |

3. Narrative Emotion as Antagonist

Archetypal Criticism reveals how certain narrative emotions function as antagonistic forces that create obstacles and drive conflict. Carl Jung’s concept of the Shadow archetype applies directly to emotions like rage, envy, or obsession when they operate as story antagonists rather than character traits.

In Homer’s Iliad, rage doesn’t simply motivate Achilles—it becomes the story’s primary antagonist. The epic’s opening line announces this directly: “Sing, goddess, the rage of Achilles.” This rage operates as a mythic force that destroys friendships, prolongs war, and ultimately consumes the hero who serves it. The emotion behaves like a classical monster, demanding sacrifice and creating chaos.

Similar to the legendary creatures found in folklore, the emotion of envy in Othello is beyond reason and cannot be appeased. Iago’s manipulation succeeds because he understands envy’s nature as a destructive force that feeds on itself. The emotion doesn’t require external validation—it creates its own evidence and grows stronger through resistance. Like the mythic monsters of folklore, envy in Othello cannot be reasoned with or satisfied.

Modern literature carries on this legacy, albeit in more nuanced ways. In Donna Tartt’s The Secret History, guilt operates as an archetypal antagonist that pursues the characters across time and geography. The emotion behaves like a classical fury, bringing consequences that feel both deserved and excessive. The students cannot escape their guilt through confession, denial, or rationalization—it transforms their relationships and ultimately destroys their attempts at normal life.

This archetypal approach to narrative emotion draws on deep psychological patterns that readers recognize intuitively. The Shadow archetype represents the aspects of human nature we cannot fully control or integrate. When emotions like obsession or revenge operate as story antagonists, they tap into primal fears about losing control of our emotional lives.

The technique works because these emotional antagonists operate according to their own logic rather than rational problem-solving. Characters cannot defeat rage through anger management or overcome envy through gratitude exercises. The emotions behave like archetypal forces that require mythic solutions—sacrifice, transformation, or acceptance of tragic consequences.

| Archetypal Emotion | Mythic Function | Narrative Role | Character Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rage | Destructive force | Primary antagonist | Consumes rational thought |

| Envy | Corrupting influence | Relationship destroyer | Creates distorted perception |

| Obsession | Possessing spirit | Driving compulsion | Eliminates free choice |

| Guilt | Pursuing fury | Moral antagonist | Demands justice or punishment |

4. Narrative Emotion as Emotional Setting and Weather

Narrative emotion creates the emotional climate of scenes, functioning like weather that affects everything within its atmosphere. This technique treats emotions as environmental conditions rather than personal experiences, allowing them to saturate settings and influence the rhythm of prose itself.

In Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, despair operates as the story’s weather system. The emotion doesn’t simply affect the father and son—it colors the ash-covered landscape, influences the pacing of their journey, and determines which details the narrative emphasizes. The atmosphere of despair renders each instance of affection invaluable, while every danger appears to be a matter of existence.

Virginia Woolf mastered this technique in novels like Mrs. Dalloway, where different emotional climates move through London like weather fronts. Clarissa Dalloway’s party preparations occur within an atmosphere of social anxiety, while Septimus Warren Smith’s breakdown happens under the emotional pressure of war trauma. These emotional weather systems don’t remain separate—they influence each other and create the story’s complex emotional ecosystem.

The technique works by treating emotions as atmospheric conditions that characters move through rather than generate. In Toni Morrison’s Beloved, the emotional climate of traumatic memory saturates the house on Bluestone Road. Characters respond to this emotional weather by avoiding certain rooms, speaking in whispers, or feeling inexplicably tired. The emotion behaves like humidity—invisible but affecting everything.

This environmental approach to emotion allows writers to create emotional consistency across scenes while maintaining character complexity. The emotional weather provides continuity even as individual characters experience different feelings. In Graham Greene’s The Heart of the Matter, the emotional climate of moral compromise affects every character’s choices, even those who consider themselves innocent.

The prose rhythm often reflects the emotional weather. Sentences become shorter and more fragmented during scenes of anxiety, while passages of grief might flow in longer, more meditative rhythms. The emotion influences not just what happens but how the story tells itself.

Writers can layer different emotional climates to create complex atmospheric effects. A scene might combine the humid pressure of suppressed anger with the cold clarity of approaching loss, creating an emotional environment that feels both specific and universal.

| Emotional Weather | Atmospheric Effect | Prose Impact | Character Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grief as fog | Obscures clear thinking | Slower, dreamlike pacing | Characters move carefully |

| Tension as humidity | Creates oppressive atmosphere | Short, clipped sentences | Characters avoid confrontation |

| Joy as sunlight | Illuminates previously hidden details | Expanded, generous descriptions | Characters notice beauty |

| Fear as gathering storm | Builds anticipation of disaster | Accelerating rhythm | Characters seek shelter |

5. Narrative Emotion as Identity and Voice

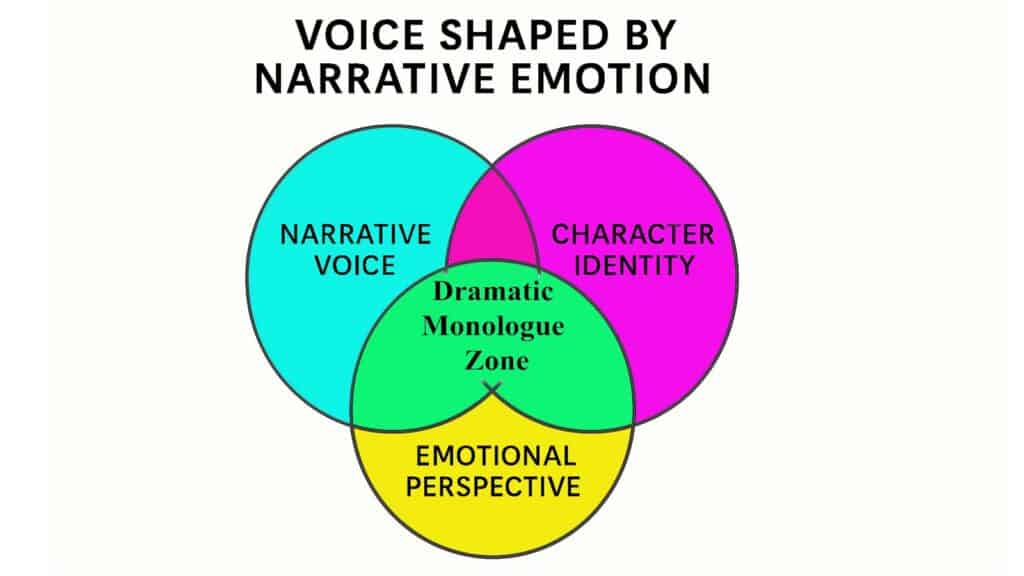

The Dramatic Monologue tradition reveals how narrative emotion shapes narrative voice, making internal emotional states become external identity. Robert Browning’s dramatic monologues demonstrate how emotional perspective doesn’t simply color storytelling—it becomes the storytelling itself.

In Browning’s “My Last Duchess,” the Duke’s possessive jealousy doesn’t just influence his account of his deceased wife—it becomes the organizing principle of his entire worldview. The emotion shapes his vocabulary, determines which details he emphasizes, and creates the blind spots that reveal his character to readers. The narrative voice and the emotional state become inseparable.

Contemporary writers continue this tradition with sophisticated variations. Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day demonstrates how repressed emotion can become a narrative voice’s defining characteristic. Stevens, the butler, exhibits emotional restraint that not only influences his actions but also transforms into his mode of expression, his perspective on life, and ultimately, his downfall. The emotion operates as both content and form.

This technique works by making emotional states into cognitive frameworks. When guilt operates as narrative voice, it doesn’t just make characters feel bad—it changes how they organize information, what they remember, and how they interpret events. The emotion becomes a way of thinking rather than simply a way of feeling.

Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita provides a complex example of how obsession can become narrative identity. Humbert Humbert’s obsession doesn’t simply motivate his actions—it becomes his entire mode of perception and expression. The beautiful, disturbing prose emerges from this emotional state, making readers experience the seductive power of the narrator’s distorted worldview.

The dramatic monologue tradition emphasizes how emotional perspective creates unreliable narration. Characters who narrate from within strong emotional states cannot see themselves clearly, creating gaps between what they intend to communicate and what they actually reveal. These gaps become spaces where meaning accumulates.

This approach to narrative voice recognizes that emotions are not simply internal experiences but ways of organizing reality. When characters speak from within specific emotional states, they create versions of the world that feel complete and logical from their perspective while remaining clearly distorted to readers.

| Voice of Narrative Emotion | Narrative Characteristic | Reader Experience | Various Literary Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obsessive love | Idealization and rationalization | Uncomfortable fascination | Nabokov’s Lolita |

| Repressed grief | Formal restraint with emotional undertones | Empathetic recognition | Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go |

| Defensive pride | Justification through selective memory | Ironic understanding | Browning’s “My Last Duchess” |

| Traumatic memory | Fragmented, circular narration | Visceral emotional response | Morrison’s Beloved |

6. Narrative Emotion as Memory and Ghost

Narrative emotion often returns as memory, reshaping present experience and creating haunting effects that outlast the original emotional events. This ghostly quality allows past emotions to influence current action, making time fluid within the story’s emotional landscape.

In Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried, the narrative emotion of war trauma doesn’t remain in Vietnam—it follows the soldiers home, altering their perception of peacetime reality. The emotion operates like a ghost that makes ordinary moments feel dangerous and safe spaces feel temporary. Memory becomes a place where past and present emotions collide.

This ghostly function of narrative emotion appears clearly in trauma literature. In Art Spiegelman’s Maus, the emotional legacy of surviving the Holocaust profoundly affects both the survivor and his son. The narrative emotion doesn’t simply record historical events—it creates an emotional inheritance that shapes the second generation’s understanding of safety, family, and identity.

The technique works by treating emotions as persistent forces that resist resolution. Unlike plot conflicts that move toward resolution, these emotional ghosts return cyclically, triggered by seemingly unrelated events. A particular smell, phrase, or gesture can summon the full emotional weight of past experience into present narrative time.

Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy demonstrates how collective trauma creates emotional ghosts that haunt entire communities. The narrative emotion of shell shock doesn’t affect only individual soldiers—it transforms the emotional landscape of post-war Britain, influencing how people communicate, form relationships, and understand their own country.

This narrative’s memorial function evokes intricate temporal dynamics. Characters live simultaneously in multiple time periods, responding to present events through the emotional logic of past experience. The narrative present becomes layered with emotional history, making simple actions carry complex emotional weight.

The ghost metaphor proves particularly apt because these emotional presences cannot be eliminated through rational analysis or direct confrontation. They require acknowledgment, integration, or ritualistic release. Like literary ghosts, they demand attention to unfinished emotional business.

| Ghosts of Narrative Emotion | Triggering Mechanism | Narrative Effect | Resolution Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traumatic loss | Sensory associations | Sudden temporal shifts | Requires witnessing or ritual |

| Childhood shame | Authority figures or judgment | Regression to younger emotional state | Needs adult reintegration |

| Betrayal memory | Trust situations | Hypervigilance and suspicion | Demands new relationship model |

| Nostalgic longing | Familiar places or objects | Idealization of past | Requires acceptance of change |

Conclusion: When Narrative Emotion Stays Behind

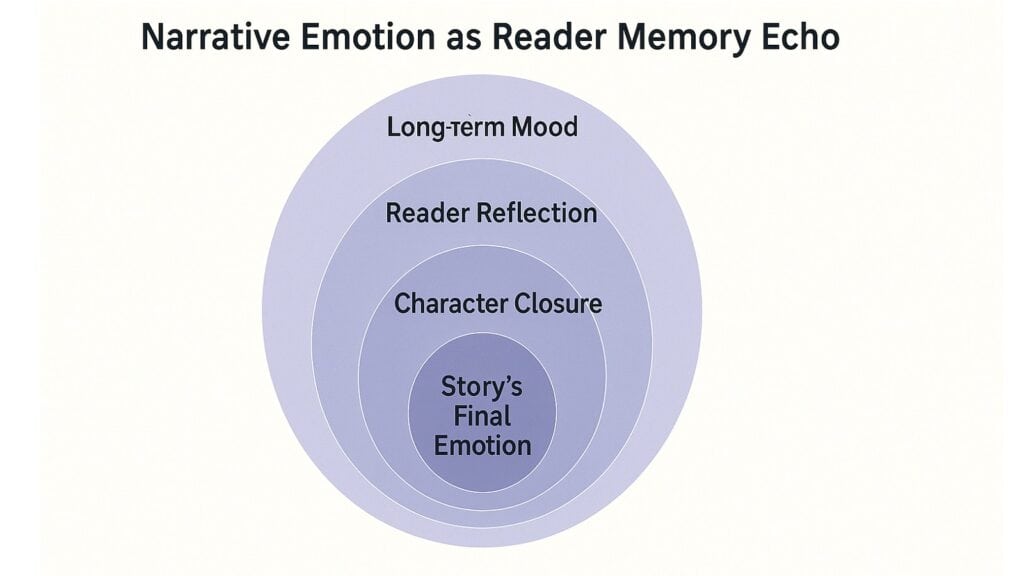

Narrative emotion operates like a visitor who changes the house simply by entering it. Long after the emotional crisis passes, long after characters resolve their conflicts, something in the story’s atmosphere remains altered. The emotion leaves traces in the narrative that continue influencing how we remember and interpret the story.

The six ways narrative emotion shapes stories reveal its fundamental difference from character emotion. While characters experience feelings that drive their actions, narrative emotion creates the conditions under which those feelings become meaningful. It operates as both content and structure, shaping what happens and how we understand what happens.

This distinction matters because it explains why certain stories continue resonating long after we forget their plots. The narrative emotion of missed connection in Chekhov’s stories outlasts our memory of specific character details. The emotional atmosphere becomes the story’s most lasting element, the part that returns to us in quiet moments when we encounter similar emotional climates in our own lives.

Understanding narrative emotion as a craft element allows writers to create stories that operate on multiple levels simultaneously. The surface narrative provides intellectual engagement, while the emotional architecture creates the deeper experience that makes stories feel necessary rather than simply entertaining.

The technique also explains why some stories feel emotionally true even when their plots seem improbable. When narrative emotion aligns with authentic emotional experience, readers accept fictional situations that might otherwise seem forced or artificial. The emotional authenticity enhances the story’s believability.

Perhaps most importantly, narrative emotion creates the bridge between individual reading experience and universal human experience. While each reader brings personal emotional history to the story, narrative emotion provides the shared emotional language that makes literary communication possible. It transforms private reading into a form of emotional communion between writer and reader.

The stories that stay with us longest understand this power. They create emotional experiences that feel as real as memory, as persistent as our own emotional ghosts. They prove that the deepest purpose of narrative isn’t simply to entertain or inform, but to expand our emotional vocabulary and deepen our capacity for feeling.

| Narrative Emotion Impact | Immediate Effect | Long-term Resonance | Reader Transformation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creates emotional memory | Shapes reading experience | Influences interpretation of life | Expands emotional vocabulary |

| Establishes emotional truth | Validates fictional events | Provides template for understanding | Deepens empathy capacity |

| Builds emotional architecture | Structures story meaning | Creates lasting impression | Offers new ways of feeling |

| Forms emotional communion | Connects reader and writer | Transcends individual experience | Enables shared emotional language |