Table of Contents

Introduction: The Hidden Pulse of Moral Framing in Storytelling

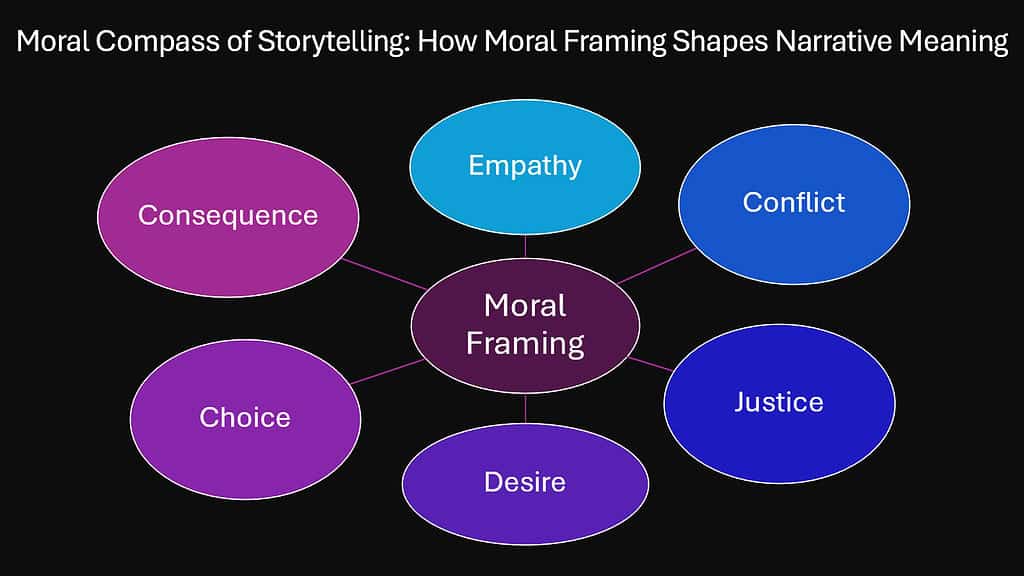

A hero walks into fire to save a stranger. Another character lies to protect someone they love. Why does one choice feel noble while the other feels desperate? The answer lives in moral framing—the invisible architecture that tells us what matters and why. Long before the first sentence ends, every powerful story has already begun whispering its moral language. It shapes how we see courage, betrayal, justice, and desire without ever delivering a sermon.

Moral framing is the compass needle beneath every narrative decision. It determines which actions we celebrate and which we condemn. It turns a bank robbery into either a crime or a revolution. This invisible force operates in the background of all great storytelling, from ancient epics to modern cinema. The Iliad frames honor as worth dying for. The Godfather frames family loyalty as both sacred and poisonous. These moral perspectives don’t just color the story—they are the story. Without them, characters become hollow and conflicts become noise.

What makes moral framing so essential is its quiet power. Audiences rarely notice they are being guided through a moral landscape. They simply feel the weight of choices and the pull of consequences. When Walter White cooks methamphetamine to provide for his family, we understand his logic even as we watch him descend. The moral frame shifts gradually, redefining what we thought we knew about desperation and pride. Stories don’t survive on plot alone. They need moral gravity to make moments register as meaningful rather than random.

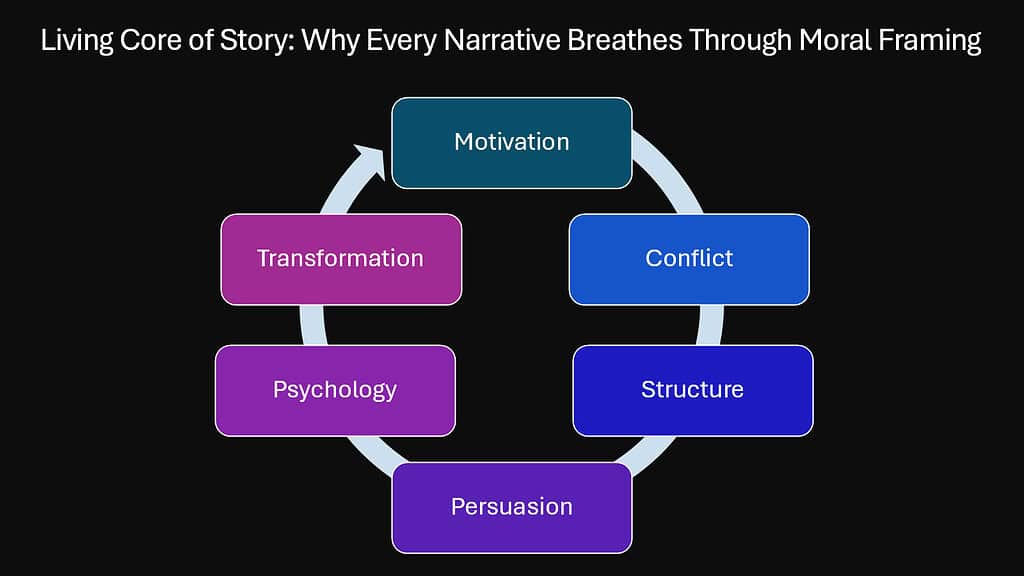

The following six sections reveal how moral framing operates at every level of storytelling. It defines why characters act. It creates conflict that resonates beyond simple opposition. It structures meaning through contrasts and binaries. It persuades audiences to align with complicated choices. It taps into universal human values. And it transforms characters through redemption or ruin. Understanding moral framing means understanding why stories matter at all.

Table 1: Moral Framing Compared to Other Storytelling Psychologies

| Storytelling Psychologies | Primary Function | Relationship to Moral Framing |

|---|---|---|

| Narrative Hook | Captures initial attention through intrigue or mystery | Creates curiosity but relies on moral framing to sustain emotional investment in outcomes |

| Emotional Arc | Maps the rise and fall of emotional intensity across the narrative | Emotional peaks gain meaning through moral stakes; feelings alone don’t clarify why we care |

| Mirror Effects | Reflects audience experiences and identities back to them | Works best when moral framing aligns character struggles with universal ethical dilemmas |

| Plot Twists | Subverts expectations through surprise revelations | Twists land hardest when they reframe moral understanding of events or characters |

| Worldbuilding | Constructs the physical and cultural environment of the story | Provides context but needs moral framing to define what behaviors or values matter in that world |

| Subtext | Communicates meaning beneath surface dialogue and action | Often carries moral judgment through implication rather than explicit statement |

| Suspense | Creates tension through uncertainty about future events | Tension deepens when outcomes have moral consequences beyond simple success or failure |

1. Moral Framing and Character Motivation: The Core of Narrative Drive

Characters don’t just want things. They want things that mean something. A man seeks revenge not merely to balance scales but to restore a sense of cosmic justice. A woman sacrifices her career not just from obligation but because she frames family as sacred. Moral framing transforms goals into quests by attaching ethical weight to every choice. Without this dimension, characters drift through events without purpose. With it, every action becomes a statement about what matters.

Walter White in Breaking Bad begins with a motivation that feels pure—providing for his family after death. The moral frame initially positions him as tragic and sympathetic. But as the series progresses, the frame shifts. His actions reveal deeper drives rooted in pride and power. The show continuously reframes his choices, forcing audiences to reassess whether his original motivation was ever truly about family. This reframing creates the series’ central tension. We watch not just what Walter does but how we are meant to interpret why he does it.

Macbeth offers another example of motivation shaped by moral perspective. His desire for power becomes monstrous not because ambition itself is evil but because the play frames his specific path—murdering a king—as a violation of natural and divine order. Shakespeare surrounds Macbeth’s actions with language of blood, darkness, and unnatural occurrences. The moral frame makes clear that this particular ambition corrupts everything it touches. The tragedy comes from watching Macbeth know this truth and proceed anyway. His motivation is framed as both understandable and damning.

The emotional pull of any story depends on how clearly or ambiguously it frames motivation. When moral clarity exists, audiences feel confident in their judgments. When moral confusion reigns, they experience the discomfort of uncertainty. Both approaches work, but they create different kinds of engagement. Clear framing creates catharsis. Ambiguous framing creates reflection. The choice depends on what the story wants its audience to feel when the final page turns.

Table 2: Character Motivation Through Moral Frames in Classic Narratives

| Story | Character | Surface Motivation | Moral Framing | Narrative Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breaking Bad | Walter White | Provide for family through illegal means | Initially framed as desperate father; gradually reframed as prideful criminal | Audience sympathy erodes as moral frame shifts |

| Macbeth | Macbeth | Seize throne through murder | Framed as violation of divine and natural order | Actions coded as corrupting force rather than legitimate ambition |

| The Count of Monte Cristo | Edmond Dantès | Seek revenge against betrayers | Framed as righteous justice earned through suffering | Revenge becomes morally complex as collateral damage emerges |

| The Great Gatsby | Jay Gatsby | Win back lost love through wealth | Framed as both romantic devotion and dangerous delusion | Dream itself becomes morally ambiguous pursuit |

| Les Misérables | Jean Valjean | Build new life after redemption | Framed as moral transformation versus legal judgment | Law and morality exist in tension throughout |

2. Moral Framing and Conflict: The Battle of Ethical Worlds

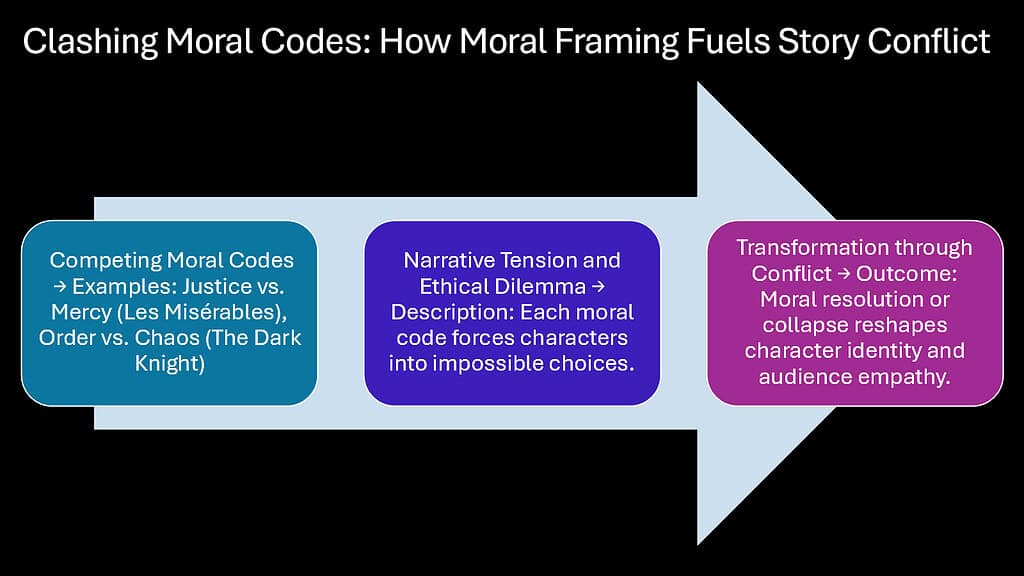

Conflict becomes compelling when characters don’t just disagree but inhabit different moral universes. A detective believes justice requires following every rule. A vigilante believes justice demands breaking them. Both want justice, but their moral frameworks make compromise impossible. This is where narrative tension lives—not in simple opposition but in the collision of incompatible moral logics. The most powerful conflicts force audiences to understand both perspectives even when they can’t reconcile them.

Les Misérables builds its entire structure on moral conflict between systems. Jean Valjean operates from a morality of mercy and redemption. Inspector Javert operates from a morality of law and order. Neither man is simply wrong. Both moral frameworks have logic and consistency. The tragedy comes from their mutual exclusivity. Javert cannot accept that a criminal might deserve mercy without unraveling his entire worldview. Valjean cannot accept that rigid law serves justice when it crushes human dignity. Their conflict feels inevitable because their moral frames cannot coexist.

The Dark Knight explores similar territory through Batman and the Joker. Batman frames justice as something that must operate within moral limits even when fighting chaos. The Joker frames those limits as arbitrary illusions. Their conflict isn’t about stopping crime versus causing it. It’s about whether moral frameworks mean anything at all in a universe of violence and randomness. Every scene between them tests whether Batman’s moral boundaries will hold or collapse. The stakes feel enormous because the conflict isn’t about who wins a fight but whose moral vision defines reality.

Internal conflict works the same way. A character torn between duty and love doesn’t just face a hard choice. They face two moral frames that both feel legitimate. Duty says loyalty to community supersedes personal desire. Love says authentic connection matters more than abstract obligation. Neither frame is inherently superior. The character must choose not just what to do but which moral logic to privilege. That choice reveals who they are and what they believe the universe rewards or punishes.

Table 3: Moral Conflict Structures in Narrative

| Story | Conflicting Moral Frames | Characters Embodying Frames | Resolution Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Les Misérables | Mercy versus law; redemption versus punishment | Jean Valjean versus Inspector Javert | One frame proves insufficient; rigid law collapses when tested by reality |

| The Dark Knight | Order through limits versus freedom through chaos | Batman versus Joker | Frames remain in tension; victory is survival of moral boundaries not resolution |

| A Few Good Men | Truth and justice versus security and order | Lieutenant Kaffee versus Colonel Jessup | Institutional authority exposed as corrupted version of protective duty |

| Parasite | Economic survival versus class dignity | Kim family versus Park family | Both frames collapse into violence when inequality makes coexistence impossible |

| Sophie’s Choice | Impossible moral calculation under evil system | Sophie forced to choose between children | No resolution possible; moral framing itself breaks under extreme conditions |

3. Moral Framing through the Lens of Structuralism: The Binary of Good and Evil

Structuralism teaches that meaning emerges through opposition. We understand light because darkness exists. We recognize courage because cowardice provides contrast. Stories operate on this principle at their deepest level. Moral framing depends on binary structures—good versus evil, justice versus corruption, freedom versus oppression. These oppositions aren’t simplistic. They’re fundamental to how humans organize meaning. Every story builds its moral architecture on these contrasting foundations even when it later complicates them.

Star Wars offers the clearest example of moral binaries in modern storytelling. The Force divides into light and dark. Characters choose sides that correspond to broader moral categories. The Rebel Alliance represents freedom and hope. The Empire represents tyranny and control. These binaries make the stakes immediately comprehensible. Audiences don’t need exposition to understand why the Rebellion matters. The moral structure communicates through pure opposition. Later complexity comes from characters like Darth Vader who occupy both poles, but that complexity only works because the binary exists first.

The Lion King uses similar structural oppositions. Simba represents rightful order and natural harmony. Scar represents disruption and corruption. The Pride Lands flourish under good leadership and decay under evil. The binary isn’t subtle, but that directness serves the story’s purpose. Young audiences grasp the moral stakes instantly. The structure teaches moral categories through contrast. What makes the story sophisticated is how it shows Simba must earn his position in the moral binary rather than inheriting it automatically.

The most interesting narratives blur these binaries without destroying them entirely. They show good people doing terrible things or evil people showing unexpected kindness. But even blurred binaries depend on the original categories to create meaning. We can only recognize moral complexity when we first understand moral clarity. Stories that try to abandon binaries altogether often feel diffuse and unmotivated. The opposition between moral poles creates the tension that drives narrative forward and helps audiences navigate meaning.

Table 4: Structuralist Binary Oppositions in Moral Framing

| Story | Primary Binary Opposition | How Binary Creates Meaning | Moments of Blurring or Complication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Star Wars | Light side versus dark side of Force | Defines character allegiances and stakes of galactic conflict | Darth Vader’s redemption crosses binary; gray Jedi suggest middle ground |

| The Lion King | Natural order versus corrupt disruption | Establishes Simba’s moral right to rule and Scar’s illegitimacy | Simba’s guilt and exile show earning moral position requires personal growth |

| Lord of the Rings | Free peoples versus Sauron’s domination | Creates unity among diverse groups against clear existential threat | Characters like Gollum and Boromir show how good people can be tempted |

| Harry Potter | Love and sacrifice versus power and control | Separates heroes from antagonists through moral choices not abilities | Snape’s true loyalties reveal binary isn’t always visible on surface |

| The Handmaid’s Tale | Human dignity versus totalitarian control | Frames every act of resistance as morally significant | Some enforcers are victims; some victims become enforcers |

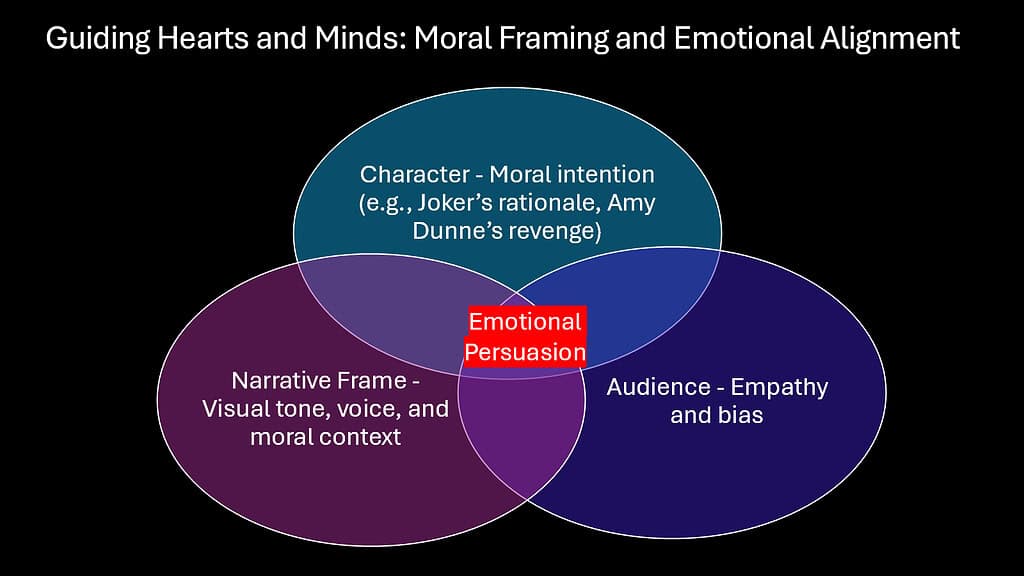

4. Moral Framing and Audience Alignment: The Art of Emotional Persuasion

Stories don’t just present moral frames. They guide audiences into adopting specific moral perspectives. This happens through carefully controlled information, point of view, and emotional cues. Viewers root for characters not because those characters are objectively good but because the story frames them as worth supporting. This is narrative persuasion at its most subtle. Camera angles, music, and whose thoughts we access all push audiences toward particular moral alignments even when those alignments might seem questionable from a different angle.

Joker demonstrates this persuasive power. Arthur Fleck commits acts of violence that should repel audiences. But the film frames his perspective as primary. We see his suffering, humiliation, and isolation. We understand the logic that leads to his actions even if we don’t endorse it. The moral framing doesn’t justify violence, but it creates empathy by showing how someone arrives at monstrous choices. The controversy around the film came from its success at making audiences feel aligned with a character who shouldn’t be sympathetic.

Gone Girl employs moral framing to continuously shift audience alignment. The first half positions Amy as victim and Nick as suspicious husband. Then the frame flips. Amy becomes calculating manipulator while Nick becomes sympathetic trapped victim. Neither frame is complete truth. The novel plays with how easily narratives can reframe the same facts to support opposite moral judgments. The story demonstrates that moral framing isn’t about truth but about which details receive emphasis and from whose perspective events are witnessed.

Writers control alignment through seemingly small choices. Whose internal thoughts do we hear? Whose pain receives screen time? Which character’s goals structure the plot? These decisions guide emotional investment without audiences recognizing the manipulation. A character who receives more narrative focus becomes more sympathetic almost automatically. This doesn’t mean audiences lack critical thinking. It means stories operate on emotional and intuitive levels where moral frames feel natural rather than constructed.

Table 5: Techniques of Moral Alignment in Storytelling

| Technique | How It Guides Alignment | Example | Effect on Audience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point of view access | Audiences align with characters whose thoughts they share | Gone Girl reveals Amy’s planning, creating understanding of her logic | Sympathy follows access to internal justification regardless of actions |

| Emotional close-ups | Visual focus on suffering creates empathy | Joker shows Arthur’s pain in intimate detail | Audiences feel connected to character’s emotional reality |

| Narrative structure | Plot organized around specific character’s goals | Breaking Bad follows Walter’s perspective despite moral descent | Investment in character’s success continues even as actions worsen |

| Contextual information | Backstory explains why characters act as they do | Killmonger in Black Panther has legitimate grievances | Villain becomes morally complex rather than simply evil |

| Comparative framing | Character looks better or worse depending on who they’re contrasted with | The Sopranos shows Tony Soprano beside worse criminals | Relative morality shapes judgment more than absolute standards |

5. Moral Framing through the Lens of Moral Foundations Theory: The Psychology of Values

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt identified several universal moral foundations that appear across cultures—care versus harm, fairness versus cheating, loyalty versus betrayal, authority versus subversion, and sanctity versus degradation. Stories resonate globally when they tap into these fundamental moral intuitions. Moral framing in narratives often aligns with one or more of these foundations, creating emotional responses that transcend cultural boundaries. The most powerful stories understand which moral foundations they’re activating and use them deliberately.

To Kill a Mockingbird activates the care and fairness foundations. Atticus Finch defends Tom Robinson because the trial violates both fairness and basic human care. The story frames racial injustice as both a failure of fair systems and a failure of human compassion. These dual foundations make the novel’s moral message feel urgent and universal. Readers from different backgrounds recognize the violation even if their cultures have different specific norms. The underlying moral intuitions remain constant.

Ramayana draws heavily on loyalty and authority foundations. Rama’s exile and his relationship with his duties as son and king test loyalty to family and respect for proper authority. The epic frames dharma—righteous duty—as the highest moral value. Characters who violate their proper roles create cosmic disorder. This moral framework resonates across generations because it speaks to deep intuitions about social harmony and proper behavior within hierarchies. The specific cultural context is Hindu, but the moral foundations are human.

Parasite activates fairness and care foundations while exposing how economic systems violate both. The Kim family’s deception feels understandable because they exist in a society that denies them fair opportunity or care. The Park family’s obliviousness feels damning because they benefit from a system that harms others. The film’s moral power comes from showing how inequality corrupts the fundamental moral intuitions that should govern human relationships. Both families are trapped in moral frameworks that make authentic care or fairness impossible.

Table 6: Moral Foundations Theory Applied to Global Narratives

| Story | Primary Moral Foundations Activated | Cultural Context | Universal Resonance |

|---|---|---|---|

| To Kill a Mockingbird | Care/harm and fairness/cheating | American racial injustice in 1930s | Violation of fair treatment and basic compassion transcends specific cultural moment |

| Ramayana | Loyalty/betrayal and authority/subversion | Hindu concept of dharma and proper social roles | Tension between personal desire and duty appears across all cultures |

| Parasite | Fairness/cheating and care/harm | South Korean class inequality | Economic injustice and its moral corruption resonates in any stratified society |

| The Kite Runner | Loyalty/betrayal and sanctity/degradation | Afghan culture and friendship across class lines | Guilt over betrayed friendship and search for redemption are human universals |

| Things Fall Apart | Authority/subversion and sanctity/degradation | Igbo society confronting colonialism | Clash between traditional authority and external disruption echoes across colonized cultures |

6. Moral Framing and Transformation: How Redemption and Corruption Shape Meaning

Character arcs become meaningful only within moral contexts. A person changing jobs isn’t inherently significant. A person moving from selfishness to sacrifice becomes a redemption story. Another moving from idealism to brutality becomes a corruption story. The transformation matters because moral framing gives it weight. We measure characters not just by what they do but by how their moral position shifts across the narrative. These movements define whether stories feel hopeful or tragic.

The Shawshank Redemption traces Andy Dufresne’s journey from imprisoned innocent to moral victor. The film frames his transformation not as personality change but as moral endurance. Andy maintains his dignity and humanity despite a system designed to crush both. His escape becomes morally triumphant because he refuses to let corruption define him. Red’s transformation parallels Andy’s but moves differently. Red must rediscover hope after losing it to institutional life. Both arcs work because the film clearly frames what moral positions they begin and end in.

Scarface shows the opposite trajectory. Tony Montana starts with ambition that could go anywhere. The film gradually frames his rise as moral descent. He betrays allies, destroys relationships, and loses everything human for the sake of power. His physical fall from the mansion balcony is just the external manifestation of his long moral collapse. The ending feels inevitable not because crime doesn’t pay but because the moral logic of his choices leads only to isolation and death.

Black Swan complicates transformation by making moral categories unstable. Nina’s pursuit of perfection becomes both artistic achievement and psychological destruction. The film frames her transformation ambiguously. Is she ascending to greatness or descending into madness? The answer might be both simultaneously. Her final performance achieves perfection at the cost of her sanity and possibly her life. The moral framing remains deliberately unresolved. We witness transformation without clear judgment about whether it represents triumph or tragedy.

Table 7: Transformation Arcs and Their Moral Trajectories

| Story | Character | Type of Transformation | Moral Framing | Emotional Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Shawshank Redemption | Andy Dufresne | Endurance leading to freedom | Moral integrity maintained despite external corruption | Hope and dignity triumph over systems of oppression |

| Scarface | Tony Montana | Ambition corrupting into isolation | Success reframed as moral failure and human emptiness | Tragic inevitability of corruption’s internal logic |

| Black Swan | Nina Sayers | Artistic perfection through psychological collapse | Ambiguous relationship between achievement and destruction | Triumph and tragedy become indistinguishable |

| Schindler’s List | Oskar Schindler | Opportunism transforming into heroism | Gradual recognition of moral responsibility | Redemption earned through action despite costs |

| There Will Be Blood | Daniel Plainview | Drive becoming monstrous obsession | Capitalism and ambition as morally corrosive forces | Complete moral isolation as inevitable result |

Conclusion: Why Every Story Lives and Breathes Through Moral Framing

A story without moral framing is just a sequence of events. A car drives down a road. A person enters a room. Another person leaves. Nothing means anything until moral perspective enters. Then suddenly choices carry weight. Actions have consequences that matter beyond their immediate effects. Characters become human because their decisions reflect what they believe about right and wrong, even when those beliefs stay unspoken.

Moral framing operates at every level explored in these six sections. It defines why characters want what they want, turning goals into quests worth following. It creates conflict that resonates because incompatible moral logics collide rather than just obstacles appearing. It structures meaning through the ancient language of binary oppositions—good versus evil, justice versus chaos—that humans use to organize experience. It guides audience emotions and alignments through subtle persuasion, making us care about people we might condemn in real life. It taps into universal moral intuitions that cross cultural boundaries. And it transforms characters through arcs of redemption or corruption that only matter because moral context gives them significance.

Understanding moral framing means recognizing that stories don’t just entertain. They teach us how to see. Every narrative presents a moral universe with its own logic and values. Some universes match our own. Others challenge us to consider different frameworks. But all stories argue for some vision of what matters and why. The Godfather asks whether family loyalty justifies violence. Breaking Bad asks whether good intentions excuse terrible actions. The Dark Knight asks whether moral limits can survive chaos.

Writers who grasp moral framing don’t manipulate audiences cheaply. They sculpt moral experiences that linger long after the last page or final scene. They understand that power comes not from preaching but from showing moral complexity in action. They know that audiences don’t want to be told what to think but want to feel the weight of moral choices and their consequences. The best stories leave us slightly different than they found us, having walked through moral territory we might never encounter otherwise.

In the end, moral framing is simply the architecture of meaning. Without it, stories collapse into forgettable sequences. With it, they become experiences that shape how we understand ourselves and our world.

Table 8: Six Ways Moral Framing Powers Narrative

| Dimension of Moral Framing | Function in Storytelling | Why It Matters | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Character Motivation | Transforms wants into morally meaningful quests | Goals need ethical weight to sustain audience investment | Actions reveal not just what characters want but who they believe they should be |

| Conflict Structure | Creates tension through incompatible moral frameworks | Mere opposition feels shallow without ethical stakes | Powerful conflicts come from legitimate moral logics that cannot coexist |

| Binary Oppositions | Establishes categories of meaning through contrast | Humans organize moral reality through opposition | Even complex stories depend on foundational binaries to create comprehensible stakes |

| Audience Alignment | Guides emotional investment through moral perspective | Stories control which characters we sympathize with | Alignment follows narrative focus and access not objective moral status |

| Universal Values | Connects to cross-cultural moral intuitions | Stories resonate globally by activating shared foundations | Specific cultural contexts express universal moral concerns |

| Character Transformation | Makes change meaningful through moral trajectory | Growth or decline needs ethical context to register | Arcs matter because moral position shifts define human significance |