Table of Contents

Introduction: The Fragile Balance of Global Financial Systems

Global Financial Systems stand as the essential building blocks of our interconnected global economy. These complex networks of banks, markets, currencies, and institutions pump capital across borders, enabling trade, investment, and economic growth on an unprecedented scale. Yet like any powerful force, Global Financial Systems carry within them the seeds of both creation and destruction.

The story of modern economics reveals how these same systems that fuel prosperity can trigger devastating collapses. The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis began with currency speculation in Thailand and swept across the entire continent. The 2008 banking collapse started with subprime mortgages in American suburbs and crashed markets from London to Tokyo. The Eurozone debt crisis showed how sovereign borrowing could threaten an entire monetary union.

These episodes remind us that Global Financial Systems operate on a razor’s edge. The same mechanisms that channel savings into productive investments can become conduits for panic and contagion. The same interconnectedness that spreads opportunity also amplifies risk.

Table 1: Building Blocks of the Global Economy and the Global Financial Systems

| Building Blocks of the Global Economy | Relationship, Growth Impact, and Risk Factors |

|---|---|

| Global Trade | Provides payment systems, trade finance, and currency exchange that enable about $28 trillion in annual trade. Currency volatility can disrupt trade flows and pricing stability. |

| Labor and Migration | Facilitates global remittances of roughly $702 billion (2020), supporting around one billion migrants and their families. Capital flight and financial shocks can reduce domestic employment. |

| Technology and Innovation | Channels venture capital and R&D funding, financing about $300 billion in global VC investment (2021). Speculative bubbles in tech sectors pose financial stability risks. |

| Natural Resources | Finances extraction and infrastructure projects, enabling around $4 trillion in energy sector investments. Commodity price shocks can destabilize financial systems. |

| Governance and Institutions | Provides sovereign debt markets and development finance that support government budgets worldwide. Debt crises can undermine institutional credibility and trust. |

| Global Supply Chains | Offers trade finance and working capital, facilitating roughly $13 trillion in supply chain financing. Credit freezes can disrupt production and logistics networks. |

| Geopolitics | Channels capital flows based on political risk, driving about $1.6 trillion in annual foreign direct investment. Sanctions and conflicts increase market volatility. |

| Demographics | Funds pension systems and healthcare, managing around $32 trillion in global retirement assets. Aging populations place long-term stress on financial systems. |

| Climate and Sustainability | Mobilizes green finance, including about $540 billion in 2022, to support the renewable energy transition. Climate risks threaten asset values and long-term returns. |

1. How Foreign Direct Investment in Global Financial Systems Can Lead to Growth or Collapse

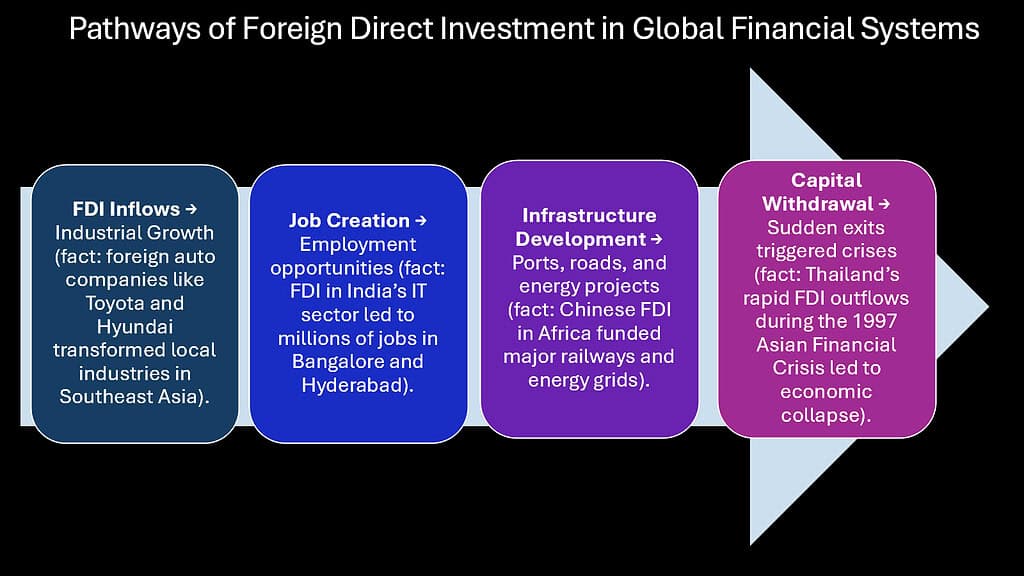

Foreign Direct Investment represents one of the most visible faces of Global Financial Systems. When multinational corporations build factories, acquire local companies, or establish regional headquarters, they inject capital, technology, and expertise into host economies. The numbers tell a compelling story: global FDI flows reached $1.6 trillion in 2022, creating millions of jobs and transferring countless innovations across borders.

The growth story of FDI unfolds in countless success stories. When Volkswagen invested billions in China during the 1980s, it helped launch that nation’s automotive industry. Samsung’s investments across Southeast Asia created industrial clusters that transformed entire regions. These investments bring more than money; they import management practices, technical knowledge, and global market access that local firms might take decades to develop independently.

Yet the same capital flows that build prosperity can vanish with frightening speed. The Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 demonstrated this cruel paradox. Countries like Thailand, Indonesia, and South Korea had welcomed massive foreign investments throughout the early 1990s. When investor confidence cracked, capital fled at breakneck speed. Factories closed, currencies collapsed, and millions lost their jobs virtually overnight.

The mechanics of this reversal reveal the dual nature of Global Financial Systems. Foreign investors, seeking higher returns in emerging markets, had poured money into Asian economies. Local banks and corporations borrowed heavily in foreign currencies to finance expansion. When global sentiment shifted, investors rushed for the exits simultaneously. The same interconnected networks that had channeled investment so efficiently became highways for capital flight.

Table 2: FDI Growth vs. Collapse Patterns – Regional Analysis

| Region | Growth Phase Characteristics | Collapse Phase Characteristics | Time Frame | Economic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Asia (1990s) | $100 billion annual FDI inflows, 8% GDP growth | $100 billion outflows in 1997-98, currencies fell 50-80% | 1990-1997 growth, 1997-1999 crisis | 20 million job losses, 5-year recovery |

| Latin America (2000s) | $150 billion peak FDI (2011), commodity boom | Sharp decline to $80 billion (2016), currency devaluations | 2003-2013 growth, 2014-2016 downturn | GDP contractions of 3-7% in major economies |

| Central Europe (2000s) | EU accession drove $50 billion annually | 2008 crisis cut flows by 60%, banking sector stress | 2004-2008 expansion, 2008-2010 crisis | Industrial production fell 20% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | China-led infrastructure FDI peaked at $50 billion | Debt sustainability concerns, project delays | 2010-2018 growth, 2019-present slowdown | Debt-to-GDP ratios rose to 60% |

2. How Portfolio Investments in Global Financial Systems Can Lead to Growth or Collapse

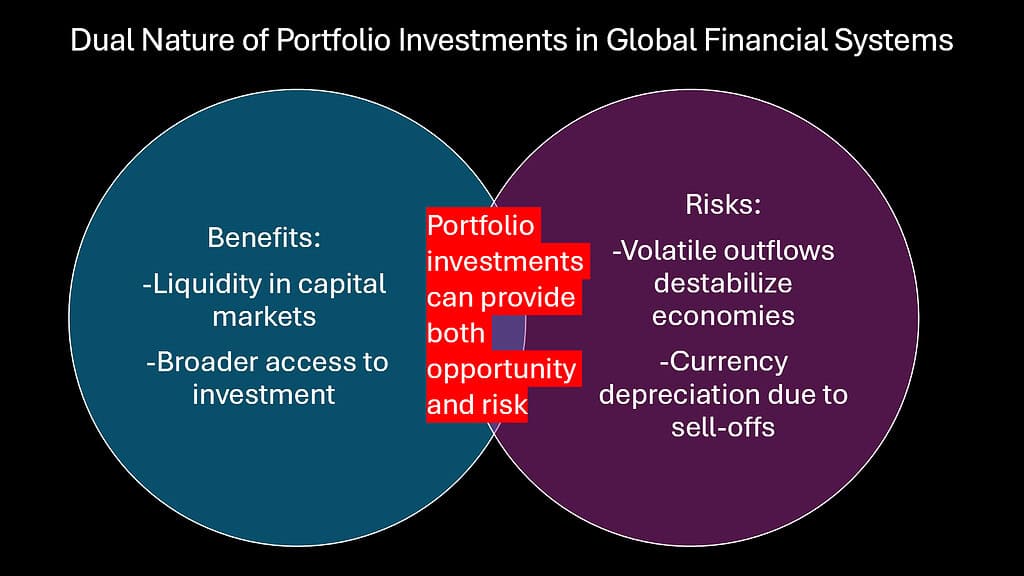

Portfolio investments flow through Global Financial Systems like electronic rivers, carrying trillions of dollars across borders in search of returns. Unlike Foreign Direct Investment, which involves long-term commitments to physical assets, portfolio flows represent purchases of stocks, bonds, and other financial securities that can be sold at the click of a mouse.

These flows serve crucial economic functions. When pension funds in developed countries buy emerging market bonds, they provide governments with capital to build infrastructure and fund social programs. When sovereign wealth funds purchase corporate stocks, they inject liquidity into markets and help companies raise capital for expansion. The International Monetary Fund estimates that portfolio flows to emerging economies averaged $300 billion annually during the 2010s, providing vital funding for development.

The growth benefits extend beyond mere capital provision. Portfolio investments deepen financial markets, making them more liquid and efficient. They bring international standards of corporate governance as foreign investors demand transparency and accountability. They also create competition among domestic financial institutions, spurring innovation and better services.

However, the mobility that makes portfolio investments so useful also makes them dangerous. The “hot money” phenomenon describes how these flows can reverse direction with stunning speed. During the 1994 Mexican peso crisis, foreign investors pulled $10 billion out of Mexican markets in just a few months. The sudden exit triggered a currency collapse and recession that took years to overcome.

The mechanics of portfolio-driven crises follow predictable patterns. Global Financial Systems amplify both optimism and pessimism through herding behavior. When markets rise, success attracts more capital, creating self-reinforcing booms. When sentiment turns, the same dynamics work in reverse. Algorithmic trading and quantitative models can accelerate these movements, as computers execute similar strategies simultaneously.

Table 3: Portfolio Investment Volatility – Boom and Bust Cycles

| Crisis Event | Peak Inflows (Annual) | Peak Outflows (Annual) | Currency Impact | Recovery Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexican Peso Crisis (1994) | $28 billion | -$10 billion | Peso fell 50% | 3 years |

| Asian Crisis (1997-98) | $93 billion (1996) | -$32 billion (1997) | Multiple currencies fell 50-80% | 5 years |

| Russian Crisis (1998) | $17 billion | -$15 billion | Ruble fell 75% | 4 years |

| Argentine Crisis (2001) | $11 billion | -$8 billion | Peso fell 70% | 6 years |

| COVID-19 Shock (2020) | Record highs in 2021 | -$26 billion (Q1 2020) | Broad EM currency weakness | 2 years |

3. How Bank Lending in Global Financial Systems Can Lead to Growth or Collapse

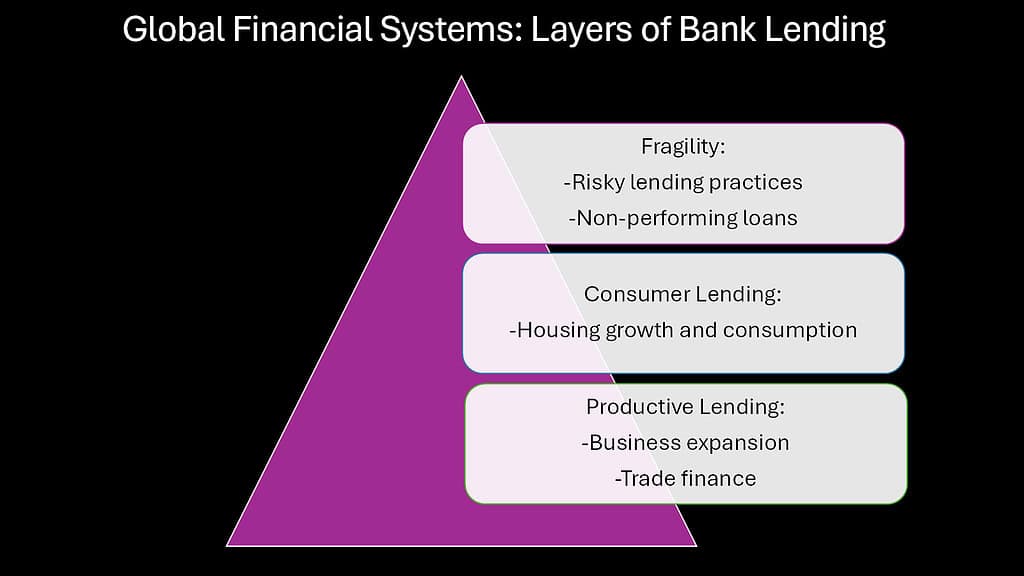

Banks form the backbone of Global Financial Systems, transforming savings into loans and enabling economic activity across every sector. When banks function well, they allocate capital efficiently, funding everything from small business expansion to massive infrastructure projects. The global banking system holds approximately $140 trillion in assets, making it one of the largest components of the world economy.

The growth-enabling power of bank lending cannot be overstated. Small businesses depend on bank loans to purchase inventory, hire workers, and expand operations. Homebuyers rely on mortgages to purchase property, creating demand that supports entire construction industries. International trade depends on letters of credit and trade finance that banks provide. Without this lending infrastructure, modern economic life would grind to a halt.

Cross-border banking through Global Financial Systems amplifies these benefits. When European banks lend to Latin American companies, they provide access to capital that might not be available domestically. When Japanese banks finance infrastructure projects in Southeast Asia, they transfer not only money but also technical expertise and international standards.

Yet the same lending mechanisms that fuel growth can become sources of systemic risk. The 2008 subprime mortgage crisis demonstrated how banking problems in one country can cascade through Global Financial Systems. American banks had made millions of housing loans to borrowers with questionable creditworthiness. When housing prices fell, these loans went bad simultaneously, threatening the entire banking system.

The crisis revealed the interconnected nature of global banking. European banks had purchased billions of dollars worth of securities backed by American mortgages. When those securities lost value, European institutions faced their own capital shortages. Credit markets froze as banks stopped lending to each other, unsure which institutions held toxic assets.

Table 4: Global Banking Expansion and Contraction Cycles

| Time Period | Cross-Border Bank Claims | Growth Drivers | Contraction Triggers | Economic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990s Expansion | $6 trillion to $12 trillion | Deregulation, emerging markets | Asian Crisis, Russian default | Regional recessions |

| 2000s Boom | $12 trillion to $34 trillion | Low interest rates, securitization | Subprime crisis, Lehman collapse | Global recession |

| Post-Crisis Recovery | $34 trillion to $29 trillion | Regulatory tightening, deleveraging | European debt crisis | Slow growth in Europe |

| Current Period | Gradual recovery to $31 trillion | Digital banking, fintech competition | COVID-19, geopolitical tensions | Uneven global recovery |

4. How Currency Trading in Global Financial Systems Can Lead to Growth or Collapse

Currency trading represents the circulatory system of Global Financial Systems, with $7.5 trillion changing hands daily in foreign exchange markets. This massive flow of money serves essential economic functions, enabling international trade and investment by allowing companies and individuals to convert one currency into another.

The growth-supporting role of currency trading often goes unnoticed because it works so smoothly. When a German car manufacturer sells vehicles in Japan, it needs to convert yen back into euros. Currency markets make this possible instantly and at competitive rates. When an American pension fund invests in Indian stocks, foreign exchange markets handle the dollar-to-rupee conversion seamlessly.

This efficiency extends far beyond simple currency conversion. Global Financial Systems use foreign exchange markets to manage risk through hedging. A Brazilian coffee exporter can lock in a favorable exchange rate months in advance, protecting against currency fluctuations that might otherwise wipe out profits. Multinational corporations use sophisticated currency strategies to optimize their global operations.

However, currency trading can transform from a stabilizing force into a destabilizing one when speculation overwhelms economic fundamentals. The 1992 attack on the British pound illustrates this transformation. George Soros and other investors borrowed billions of pounds and immediately converted them to other currencies, betting that the pound was overvalued. The selling pressure became so intense that the Bank of England could not defend the currency, forcing Britain to withdraw from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism.

The mechanics of currency crises reveal how Global Financial Systems can amplify small problems into major disasters. Once investors sense weakness in a currency, the interconnected nature of modern markets allows attacks to gain momentum rapidly. Algorithmic trading systems can execute thousands of transactions per second, accelerating currency movements beyond what human traders could achieve.

Table 5: Major Currency Crisis Episodes – Market Dynamics

| Crisis | Currency Under Attack | Speculative Pressure | Central Bank Response | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK Pound (1992) | British Pound | $10 billion in short positions | Raised rates to 15%, spent $4 billion reserves | Forced devaluation, ERM exit |

| Asian Crisis (1997) | Thai Baht, others | Massive carry trade unwinding | Multiple interventions failed | 50-80% devaluations |

| Turkish Lira (2018) | Turkish Lira | Political tensions, inflation concerns | Limited intervention capacity | 40% decline vs. dollar |

| Argentine Peso (2018) | Argentine Peso | Fiscal concerns, IMF program | $57 billion IMF bailout | 50% devaluation |

5. How Sovereign Debt in Global Financial Systems Can Lead to Growth or Collapse

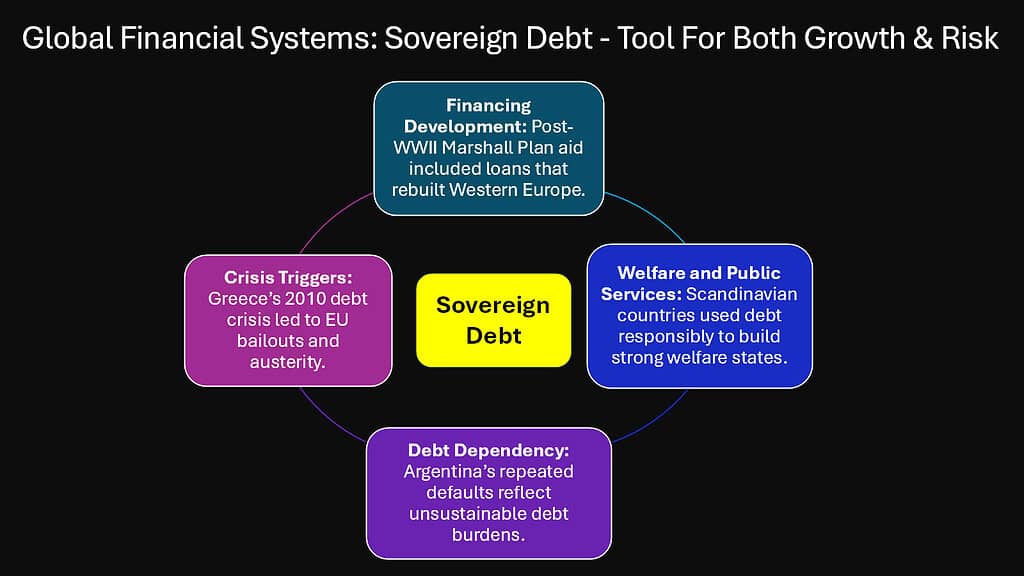

Sovereign debt markets form a cornerstone of Global Financial Systems, allowing governments to borrow money for development, infrastructure, and social programs. The global government bond market exceeds $65 trillion, representing claims on the future tax revenues of nations worldwide. When functioning properly, these markets enable countercyclical fiscal policy and long-term development planning.

The growth benefits of sovereign borrowing are substantial and often underappreciated. Governments use borrowed funds to build roads, schools, and hospitals that generate economic returns for decades. During recessions, deficit spending can prevent deeper downturns by maintaining demand when private sector activity contracts. Emerging economies have used international bond markets to finance industrialization and poverty reduction programs.

Global Financial Systems have made sovereign borrowing more efficient and accessible. A government in Africa can now tap capital markets in London, New York, or Hong Kong, accessing pools of savings that would be impossible to reach through domestic banks alone. Credit rating agencies and international standards have increased transparency, allowing investors to make informed decisions about sovereign risk.

Yet sovereign debt can become a trap when borrowing exceeds a government’s ability to service its obligations. The Greek debt crisis demonstrated how quickly confidence can evaporate. Greece had borrowed heavily during the 2000s, taking advantage of low interest rates following its adoption of the euro. When the 2008 global crisis hit, tax revenues fell while spending needs increased, creating unsustainable deficits.

The interconnected nature of Global Financial Systems meant that Greece’s problems quickly became Europe’s problems. European banks held billions of euros in Greek government bonds. A Greek default would have created losses across the continental banking system. The crisis required multiple bailout packages totaling over €300 billion and nearly destroyed the eurozone.

Table 6: Sovereign Debt Crises – Causes and Consequences

| Country/Region | Peak Debt-to-GDP Ratio | Crisis Triggers | International Response | Resolution Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latin America (1980s) | 50-60% (Mexico, Brazil) | Rising US interest rates, commodity prices | Brady Plan debt restructuring | 8-10 years |

| Argentina (2001) | 166% | Currency peg collapse, recession | Default on $95 billion debt | 15+ years |

| Greece (2010) | 180% | Fiscal deficits, eurozone contagion | €326 billion in bailout packages | 10+ years ongoing |

| Turkey (2018-2019) | 85% (including private) | Currency crisis, political tensions | IMF-style program without IMF | 3 years |

6. How Central Banks in Global Financial Systems Can Lead to Growth or Collapse

Central banks occupy a unique position within Global Financial Systems, wielding enormous influence over money supply, interest rates, and financial stability. The Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, and other major central banks collectively manage monetary policy for economies representing over 70% of global GDP. Their decisions ripple through international markets within milliseconds of announcement.

The growth-supporting role of central banks extends far beyond simple interest rate adjustments. During the 2008 financial crisis, central banks prevented a complete collapse of Global Financial Systems through unprecedented interventions. The Federal Reserve provided emergency liquidity to banks, purchased mortgage-backed securities, and established currency swap lines with foreign central banks. These actions helped stabilize markets and prevent a repeat of the 1930s Great Depression.

Central bank coordination through Global Financial Systems has become increasingly sophisticated. When the COVID-19 pandemic struck in 2020, major central banks acted in concert to provide liquidity and maintain market functioning. The speed and scale of their response demonstrated how international monetary cooperation can address global crises.

However, central bank policies can also create vulnerabilities within Global Financial Systems. Ultra-low interest rates in developed countries have driven massive capital flows to emerging markets, creating asset bubbles and currency volatility. When the Federal Reserve signals policy changes, emerging market currencies often experience sharp movements as investors adjust their portfolios.

The Turkish lira crisis of 2018 illustrated how central bank credibility affects Global Financial Systems. Turkey’s central bank faced political pressure to keep interest rates low despite rising inflation. When investors lost confidence in the bank’s independence, the lira collapsed, creating broader concerns about emerging market stability.

Table 7: Central Bank Policy Transmission Through Global Systems

| Policy Action | Direct Impact | Global Financial System Effect | Unintended Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| US Rate Hikes (2015-2018) | Dollar strengthening | $2 trillion EM capital outflows | Currency crises in Turkey, Argentina |

| ECB Quantitative Easing | Euro weakening | €2.6 trillion bond purchases | Asset bubbles, pension fund stress |

| BOJ Negative Rates | Yen carry trades | Global liquidity provision | Banking sector profitability concerns |

| PBOC Reserve Cuts | Yuan liquidity | Cross-border capital flow volatility | Housing market speculation |

7. How Interconnectedness in Global Financial Systems Can Lead to Growth or Collapse

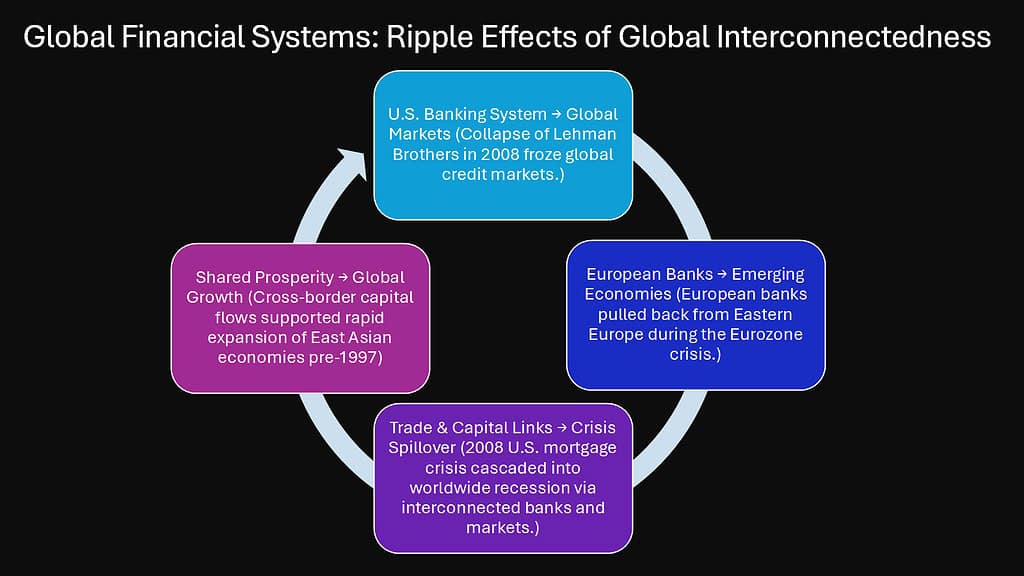

The interconnected nature of Global Financial Systems represents both their greatest strength and most dangerous weakness. Modern financial networks link every major economy through a web of banks, markets, and institutions that can transmit both prosperity and panic at the speed of light. This interconnectedness has enabled unprecedented global growth but also created systemic risks that no single country can control.

The benefits of financial interconnectedness are profound and often taken for granted. American retirees can invest in Asian growth through their pension funds. European companies can raise capital in dollar markets. African governments can access expertise from international financial institutions. This global capital allocation helps money flow to its most productive uses, regardless of geographical boundaries.

Risk sharing represents another crucial benefit. When a natural disaster strikes one region, insurance companies spread the costs across global markets. When economic conditions deteriorate in one country, international banks can provide stability by maintaining credit lines. Diversification across multiple markets reduces the impact of local economic shocks.

Yet the 2008 financial crisis revealed the dark side of interconnectedness. What began as problems with American subprime mortgages quickly spread through Global Financial Systems to become a worldwide recession. European banks that had purchased mortgage-backed securities faced capital shortages. Asian exporters saw demand collapse as Western consumers reduced spending. No country remained untouched.

The speed of contagion through Global Financial Systems has accelerated with technology. High-frequency trading algorithms can execute millions of transactions per second, potentially amplifying market movements. Social media can spread rumors and panic across continents instantly. The flash crash of 2010, when U.S. stock markets briefly lost nearly $1 trillion in value, demonstrated how interconnected systems can malfunction in minutes.

Table 8: Global Financial Interconnectedness – Network Effects

| Connection Type | Scale | Growth Benefits | Collapse Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Border Banking | $29 trillion in claims | Capital allocation efficiency | Contagion through bank failures |

| International Bond Markets | $120 trillion outstanding | Global savings mobilization | Synchronized sell-offs |

| Derivative Markets | $600 trillion notional | Risk management tools | Counterparty risk chains |

| Payment Systems | $5 trillion daily flows | Trade facilitation | System-wide payment failures |

| Digital Platforms | 4 billion users | Financial inclusion | Cyber attack vulnerabilities |

8. How New Disruptions in Global Financial Systems Can Lead to Growth or Collapse

Technological disruption is reshaping Global Financial Systems at an unprecedented pace, introducing both revolutionary opportunities and novel risks. Artificial intelligence processes millions of transactions, blockchain technology promises to eliminate intermediaries, and digital currencies challenge traditional monetary systems. These innovations could make finance more efficient, inclusive, and accessible while simultaneously creating new sources of instability.

The growth potential of financial technology appears limitless. Mobile payments have brought banking services to billions of people who were previously excluded from formal financial systems. In Kenya, the M-Pesa mobile money system processes more transactions per capita than traditional banking systems in many developed countries. Similar innovations are spreading across Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are revolutionizing risk assessment and portfolio management. Algorithms can analyze thousands of data points to make lending decisions in seconds, reducing costs and expanding credit access. Robo-advisors provide investment management services at a fraction of traditional costs, democratizing wealth management.

Cryptocurrency and blockchain technology promise even more fundamental changes to Global Financial Systems. Digital currencies could reduce the cost of international transfers, enable programmable money, and provide financial services without traditional intermediaries. Central banks are exploring digital versions of their own currencies, potentially transforming monetary policy transmission.

However, these same innovations introduce new categories of risk. Algorithmic trading can amplify market volatility, as demonstrated by multiple flash crashes. Cryptocurrency markets exhibit extreme volatility and remain largely unregulated. Cyber attacks on financial institutions could potentially disrupt entire payment systems.

The concentration of technological power among a few large companies creates additional concerns. A handful of technology giants increasingly control payment systems, data flows, and financial infrastructure. System failures or cyber attacks targeting these platforms could have widespread consequences for Global Financial Systems.

Table 9: Emerging Financial Technologies – Transformation and Risk Matrix

| Technology | Growth Potential | Current Adoption | Risk Factors | Regulatory Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Payments | $12 trillion market by 2027 | 2.8 billion users globally | Data privacy, fraud | Emerging frameworks |

| AI/Machine Learning | 50% cost reduction in operations | 85% of banks investing | Algorithmic bias, flash crashes | Principle-based guidance |

| Blockchain/DeFi | $1 trillion market cap (crypto) | $200 billion in protocols | Extreme volatility, hacks | Patchwork regulation |

| Central Bank Digital Currencies | Potential $50 trillion impact | 110+ countries exploring | Privacy concerns, bank disintermediation | Pilot programs |

| Shadow Banking | $63 trillion global assets | 45% of financial intermediation | Regulatory arbitrage, liquidity risks | Enhanced monitoring |

Conclusion: The Razor’s Edge of Global Financial Systems in the Global Economy

Global Financial Systems will continue to walk a tightrope between enabling growth and enabling collapse. The same forces that make these systems so powerful in generating prosperity also make them capable of transmitting crisis across the globe in hours or even minutes. This duality is not a flaw to be eliminated but a fundamental characteristic to be understood and managed.

The eight mechanisms explored in this analysis demonstrate that context determines outcomes in Global Financial Systems. Foreign direct investment, portfolio flows, bank lending, currency trading, sovereign debt, central banking, interconnectedness, and technological disruption can all serve as engines of growth or catalysts for collapse. The difference often lies in the quality of institutions, the wisdom of policies, and the presence or absence of external shocks.

Historical patterns suggest that Global Financial Systems will continue to evolve through cycles of innovation, expansion, crisis, and reform. Each crisis teaches lessons that inform the next generation of regulations and practices. The 1930s led to deposit insurance and securities regulation. The 1970s produced floating exchange rates and inflation targeting. The 2008 crisis generated macroprudential supervision and stress testing.

Yet new challenges continually emerge. Climate change threatens to disrupt financial systems through physical risks and transition costs. Geopolitical tensions could fragment Global Financial Systems into competing blocs. Technological disruption might outpace regulatory capacity, creating new forms of systemic risk.

The resilience of Global Financial Systems ultimately depends on our collective ability to learn from experience while preparing for unprecedented challenges. Financial markets are human constructs, reflecting our hopes, fears, and decisions. They amplify both our wisdom and our folly.

Table 10: Future Scenarios for Global Financial Systems – Resilience Factors

| Scenario | Probability | Key Drivers | Resilience Requirements | Potential Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continued Integration | Moderate | Technology, trade growth | Better regulation, coordination | Shared prosperity with periodic crises |

| Fragmentation | High | Geopolitical tensions, nationalism | Regional cooperation, crisis management | Reduced efficiency, localized instability |

| Climate Disruption | High | Physical climate impacts | Green finance, adaptation funding | Massive capital reallocation needs |

| Technological Revolution | Very High | AI, blockchain, quantum computing | Adaptive regulation, cybersecurity | Fundamental system transformation |

As we look toward the future, one question looms above all others: Will Global Financial Systems prove robust enough to support human flourishing in an era of accelerating change, or will their complexity and interconnectedness ultimately make them too fragile to sustain? The answer depends not on the systems themselves but on our collective wisdom in designing, governing, and reforming them. The razor’s edge continues to define our financial future.