Table of Contents

Introduction: Apricot Fruit Science – Why Apricot Is a Model System for Fruit Chemistry

Credit: iken3

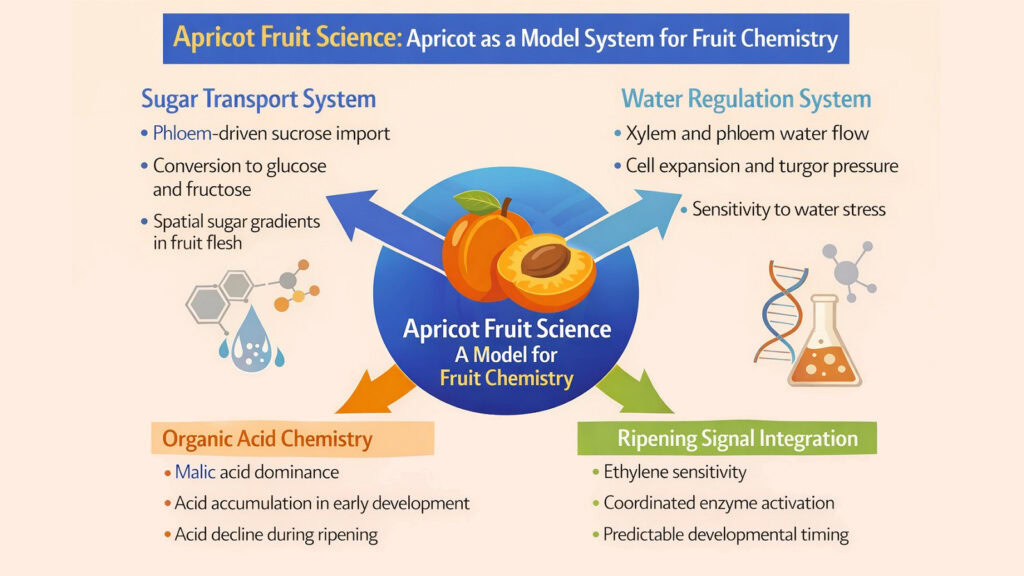

Apricot belongs to the Rosaceae fruit family, which is one of the most economically and nutritionally significant fruit families globally. Apricot stands as a compact laboratory where fruit chemistry becomes visible. Unlike larger commercial fruits that obscure internal processes through size or complexity, the apricot offers a clear window into how stone fruits organize their chemical systems. Researchers studying fruit biology often turn to apricots because their modest dimensions and rapid ripening reveal sugar transport, water regulation, and acid metabolism with unusual clarity. The fruit measures small enough to track metabolic gradients yet large enough to sample distinct tissue zones.

Stone fruits like apricots belong to Prunus, a genus that demonstrates how reproductive structures shape surrounding tissue chemistry. The hard endocarp creates a boundary that influences everything from nutrient allocation to defense compound distribution. Apricot fruit development follows predictable phases where cell division gives way to expansion, then to ripening. Each phase brings distinct chemical signatures that scientists can measure and compare across varieties.

What makes apricot particularly valuable in fruit science is its sensitivity to environmental variables. Water stress alters sugar concentration patterns within days. Temperature shifts change acid metabolism rates visibly. Harvest timing affects enzyme activity in ways that remain traceable through storage. These responsive characteristics allow researchers to test hypotheses about fruit chemistry under controlled conditions. The apricot becomes not just a subject but a measurement tool.

This article examines six internal chemical systems where Apricot Fruit Science illuminates broader principles of fruit design. We will explore sugar distribution as a structural organizer, water movement as a chemical driver, organic acids as metabolic regulators, cell wall dynamics as engineered softening, hormonal coordination as signal integration, and the stone as an evolutionary boundary. Each system operates according to biochemical rules that transcend the apricot itself, yet the apricot displays these rules with exceptional transparency.

Apricot Fruit Science: Comparative Analysis of Rosaceae Fruit Characteristics

| Rosaceae Fruits | Key Chemical and Structural Features |

|---|---|

| Apricot | Small stone fruit with rapid ripening and single large seed |

| Apples | Pome fruit with thick cuticle and extended storage capacity |

| Pears | Pome with stone cells requiring chilling for proper ripening |

| Peaches | Larger stone fruit with freestone or clingstone pit attachment |

| Plums | Stone fruit with high phenolic content and sorbitol transport |

| Cherries | Small stone fruit with rapid deterioration and high anthocyanins |

| Raspberry | Aggregate fruit composed of multiple drupelets with minimal shelf life |

| Strawberry | Accessory fruit with non-climacteric ripening pattern |

1. Apricot Fruit Science: How Sugar Distribution Shapes Internal Structure

Sugars enter apricot fruit through phloem vessels that branch into increasingly fine networks as they approach the flesh. Leaves produce sucrose through photosynthesis, and this disaccharide travels through sieve tubes under pressure. When sucrose reaches fruit tissue, invertase enzymes cleave it into glucose and fructose. This conversion happens preferentially in certain zones, creating concentration gradients that persist through ripening. The pattern is not random but follows vascular architecture established during early fruit development.

Early in development, apricot fruits accumulate sorbitol alongside sucrose. Sorbitol serves as both a transported sugar and an osmotic regulator in Rosaceae species. As the fruit matures, sorbitol levels decline while hexoses increase. This shift reflects changing enzyme activities rather than altered import rates. Sorbitol dehydrogenase converts sorbitol to fructose in a reaction that ties sugar metabolism to cellular redox state. The timing of this conversion influences when different fruit regions reach their final sweetness levels.

Sugar gradients in apricot flesh correspond to ripening order. Regions nearest the vascular bundles accumulate sugars first and soften earlier than peripheral tissues. This creates a ripening wave that moves outward from the stone. Measuring sugar distribution through tissue sectioning reveals that the gradient can span several degrees Brix across just a few millimeters. Such steep gradients indicate active transport and compartmentation rather than simple diffusion.

The relationship between sugar concentration and water content complicates simple measurements. As cells expand during fruit growth, incoming water dilutes existing sugars even as new sugars arrive. Net sugar increase depends on the balance between import rate and dilution rate. In Apricot Fruit Science, tracking this balance helps explain why fruit size and sweetness do not always correlate positively. Smaller fruits may concentrate sugars more effectively if water import slows while sugar transport continues.

Apricot Fruit Science: Sugar Transport and Metabolism Stages

| Developmental Stage | Sugar Chemistry Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Cell Division Phase | High sorbitol levels with minimal invertase activity |

| Cell Expansion Phase | Rapid water influx dilutes sugars as cells enlarge |

| Sugar Accumulation Phase | Invertase peaks converting sucrose to hexoses |

| Ripening Initiation | Starch mobilizes into soluble sugars near vascular tissue |

| Full Ripeness | Sugar distribution becomes uniform as gradients dissipate |

| Senescence | Respiration consumes sugars faster than import replaces them |

2. Apricot Fruit Science: Water Movement as a Structural and Chemical Driver

Credit: iken3

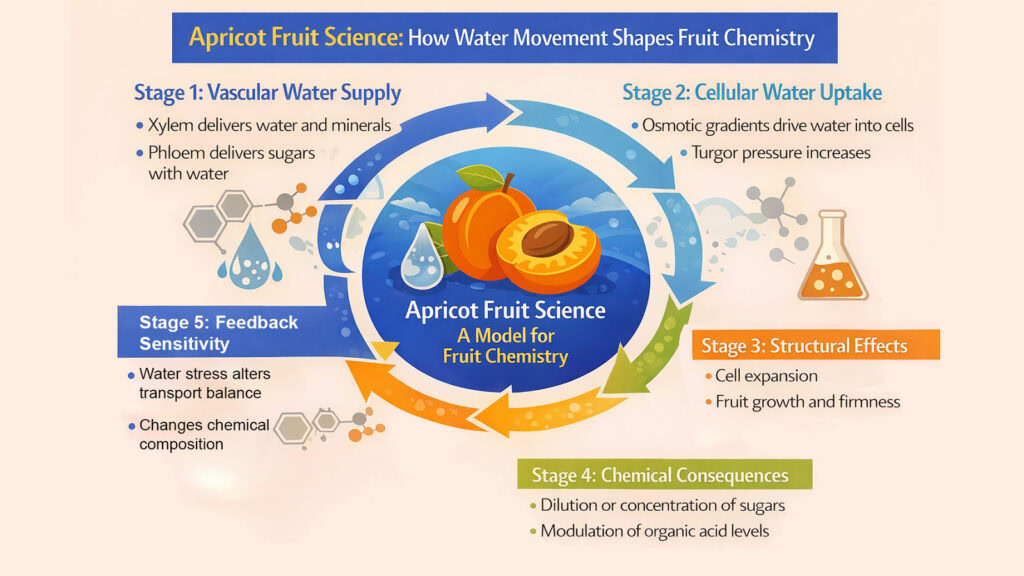

Water reaches apricot fruit through two parallel pathways with distinct chemical implications. Xylem vessels carry water pulled by transpiration from leaves, driven by negative pressure. Phloem tubes deliver water pushed by osmotic gradients created by high sugar concentrations at source tissues. These two streams merge in fruit tissue but respond differently to environmental conditions. When atmospheric vapor pressure deficit increases, xylem flow slows while phloem flow continues, shifting the ratio of water sources and altering mineral delivery patterns.

Cell expansion in developing apricots depends absolutely on turgor pressure generated by water influx. As solutes accumulate in vacuoles, water follows osmotically, pressing the cell membrane against the wall. This pressure drives cell enlargement when walls remain extensible. Apricot cells can expand to several times their initial volume during the growth phase. The final fruit size reflects not cell number but cell volume, which is ultimately a function of water accumulation capacity.

Water stress during apricot development produces measurable effects on internal chemistry within hours. Reduced water availability raises sugar concentrations through reduced dilution, but it also triggers osmotic adjustment responses. Cells synthesize compatible solutes like proline and glycine betaine to maintain turgor. These compounds accumulate alongside sugars, altering the overall solute profile. Researchers, studying science behind Apricot Fruit chemistry, use controlled water deficits to understand how plants partition resources between growth and stress protection.

Late-season water movement into apricots creates quality challenges in commercial production. Fruits approaching harvest have limited capacity for additional cell expansion. Sudden water influx from irrigation or rainfall cannot be accommodated through growth. Instead, excessive turgor leads to cell rupture and skin splitting. The apricot’s thin cuticle provides minimal resistance to water loss but also minimal protection against rapid water uptake. This sensitivity makes apricot an informative model for studying water relations in thin-skinned fruits.

Apricot Fruit Science: Water Relations and Physiological Impacts

| Water Movement Aspect | Chemical and Structural Consequences |

|---|---|

| Xylem Transport | Delivers minerals dissolved in soil water driven by transpiration |

| Phloem Transport | Carries concentrated sugar solution with phloem-mobile nutrients |

| Osmotic Regulation | Solute accumulation creates water potential gradient driving influx |

| Cuticle Properties | Thin waxy layer permits rapid humidity equilibration |

| Turgor-Driven Growth | Cell expansion requires sustained water pressure against walls |

| Water Stress Response | Triggers abscisic acid signaling and stress metabolite accumulation |

3. Apricot Fruit Science: Organic Acids and the Chemistry of Balance

Malic acid dominates the organic acid profile of developing apricots, with citric acid as a secondary component. These acids build up in vacuoles, allowing them to attain concentrations that surpass one hundred millimolar. Early in development, acid synthesis proceeds faster than dilution or consumption, so acidity rises even as the fruit expands. The acids serve multiple functions beyond pH regulation. They provide carbon skeletons for amino acid synthesis, maintain electrical balance as counterions to potassium, and modulate enzyme activities throughout the cell.

Acid decline during apricot ripening follows a characteristic pattern linked to respiration. Malic acid feeds into the tricarboxylic acid cycle, where it undergoes oxidative decarboxylation. The reaction produces NADH for energy generation while removing carbon as carbon dioxide. This metabolic consumption explains why acids decrease faster than dilution alone would predict. Temperature strongly influences the rate of acid loss because respiratory enzymes show high thermal sensitivity. Warm conditions can reduce acidity by several tenths of a pH unit in just days.

The ratio of sugars to acids defines what fruit scientists call the maturity index. For apricots, this ratio climbs steeply during the final weeks before harvest as sugars continue accumulating while acids decline. The ratio is not merely descriptive but mechanistic. High acid levels inhibit certain ripening enzymes, while rising sugar concentrations activate others. The changing ratio thus coordinates multiple biochemical pathways. In Apricot Fruit Science, tracking acid-sugar dynamics reveals how chemical feedback loops synchronize ripening.

Acid distribution within apricot fruit is not uniform. Tissue near the skin often maintains higher acidity than interior flesh, partly due to differential respiration rates. Outer cells have better oxygen access and may metabolize acids more slowly. Additionally, light exposure affects acid metabolism in surface tissues. Measuring acid gradients across fruit radii provides insight into how environmental factors penetrate into fruit chemistry. The gradients also affect texture perception since acid content influences pectin solubility and cell adhesion.

Apricot Fruit Science: Organic Acid Functions and Dynamics

| Acid Chemistry Aspect | Biochemical Role and Changes |

|---|---|

| Malic Acid Accumulation | Peaks during expansion then declines through ripening |

| Citric Acid Dynamics | Remains more stable than malate during ripening |

| pH Regulation | Vacuolar pH ranges from 3 to 4 affecting enzyme activity |

| Respiratory Substrate | Malate oxidation in TCA cycle reduces total acid content |

| Ion Balance Function | Organic acid anions balance potassium cations in cells |

| Sugar-Acid Ratio | Maturity index increases from under 5 to above 15 at ripeness |

4. Apricot Fruit Science: Cell Walls, Enzymes, and Controlled Softening

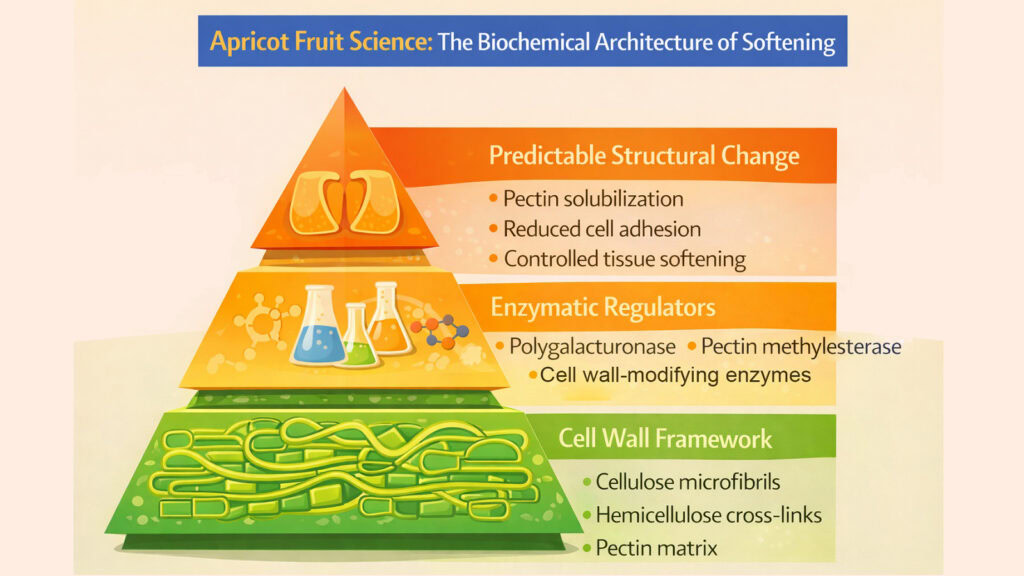

Credit: iken3

Apricot flesh firmness depends on cell wall architecture and the adhesion between adjacent cells. The primary cell wall contains cellulose microfibrils embedded in a matrix of pectins, hemicelluloses, and structural proteins. Pectin polymers in the middle lamella bind cells together through calcium bridges and covalent linkages. During ripening, enzymes modify these polymers in a precise sequence. The result is controlled softening rather than chaotic degradation. Understanding this process forms a central goal of research behind Apricot Fruit Science.

Polygalacturonase cleaves the backbone of pectin polymers, reducing their molecular weight and solubility characteristics. Apricot varieties differ substantially in polygalacturonase expression levels, explaining differences in softening rates. Pectin methylesterase removes methyl groups from pectin, exposing carboxyl groups that can form calcium bonds or become targets for polygalacturonase. These two enzymes work sequentially rather than simultaneously, creating a temporal pattern in cell wall disassembly.

Hemicelluloses link cellulose microfibrils to pectin networks, forming the wall’s load-bearing structure. Enzymes called xyloglucan endotransglucosylase-hydrolases cut and rejoin hemicellulose chains during cell expansion and ripening. In apricots, these enzymes show activity spikes that correlate with rapid softening phases. The enzymes do not destroy wall structure but rather remodel it, allowing yielding without collapse. This distinction matters because it explains how apricots can soften while maintaining structural integrity until late senescence.

Softening in apricots demonstrates how biochemistry translates into mechanical properties. Researchers can measure firmness using penetrometers that quantify resistance to deformation. Parallel measurements of enzyme activities and polymer properties show clear correlations. As polygalacturonase activity rises, pectin molecular weight drops and firmness declines. The relationships are not perfectly linear because multiple polymers contribute to firmness simultaneously. Nevertheless, cell wall chemistry accurately predicts texture changes across ripening stages in studies of Apricot Fruit Science.

Apricot Fruit Science: Cell Wall Modification During Ripening

| Cell Wall Component | Enzymatic Modification and Structural Impact |

|---|---|

| Pectin Polymers | Polygalacturonase cleaves chains reducing molecular weight |

| Cellulose Microfibrils | Remain intact providing residual structural scaffold |

| Hemicelluloses | Transglucosylase enzymes rearrange xyloglucan chains |

| Middle Lamella | Calcium-pectate bonds dissolve weakening cell adhesion |

| Expansin Proteins | Disrupt hydrogen bonds facilitating wall loosening |

| Enzyme Expression Timing | Gene transcription increases sharply with ethylene onset |

5. Apricot Fruit Science: Hormonal Signals That Coordinate Ripening

Ethylene synthesis in apricots marks the transition from growth to ripening. The fruit produces this simple hydrocarbon through a three-step pathway beginning with the amino acid methionine. ACC synthase converts S-adenosylmethionine to ACC, then ACC oxidase converts ACC to ethylene. The rate-limiting step shifts between these enzymes depending on developmental stage and stress conditions. Apricots are climacteric fruits, meaning they show a respiratory burst and rapid ethylene increase that triggers coordinate ripening changes.

Ethylene perception depends on receptor proteins in cell membranes. When ethylene binds these receptors, it initiates signal cascades that alter gene expression throughout the fruit. Hundreds of genes respond to ethylene, including those encoding enzymes for sugar metabolism, acid breakdown, cell wall modification, and volatile production. The coordinated response explains why ripening changes happen simultaneously across multiple chemical systems. In Apricot Fruit Science, ethylene serves as the master signal that synchronizes previously independent processes.

The timing of ethylene sensitivity varies across apricot varieties. Some cultivars begin responding to ethylene while still attached to the tree, ripening on the branch. Others remain insensitive until after harvest, requiring a maturation period before ripening commences. These differences reflect variation in receptor expression and signal transduction components. Breeders have selected for delayed ethylene response to extend shelf life, but this often correlates with reduced ripening capacity since the signaling system becomes less responsive overall.

Other hormones modulate ethylene’s effects in apricot fruit. Auxin levels decline as ripening approaches, removing a growth signal and permitting senescence programs to activate. Abscisic acid accumulates in response to stress and appears to prime ethylene sensitivity. Brassinosteroids influence cell expansion and may interact with ethylene signaling during early development. The interplay between hormone systems demonstrates that fruit ripening emerges from multiple signal inputs rather than from ethylene alone. This complexity challenges simple models but provides rich material for the investigation of Apricot Fruit Science.

Apricot Fruit Science: Hormonal Control of Ripening Processes

| Hormonal Aspect | Signaling Function and Downstream Effects |

|---|---|

| Ethylene Biosynthesis | ACC synthase and oxidase levels rise exponentially at ripening |

| Ethylene Receptors | Receptor binding releases transcription factors from inhibition |

| Transcription Factors | Ethylene response factors activate hundreds of ripening genes |

| Auxin Decline | Growth hormone drop permits transition to ripening metabolism |

| Abscisic Acid Role | Stress hormone enhances ethylene sensitivity through crosstalk |

| Signal Integration | Multiple hormones converge on shared signaling nodes |

6. Apricot Fruit Science: The Stone as a Chemical and Evolutionary Boundary

The apricot stone forms through lignification of endocarp cells surrounding the seed. This process creates a barrier that is chemically distinct from the fleshy mesocarp. Lignin polymers deposit in cell walls, making them impermeable and mechanically rigid. The timing of stone hardening occurs during early fruit development, coinciding with seed maturation. Once lignified, the endocarp isolates the seed from flesh, creating separate chemical environments that evolve independently during later fruit development.

Nutrient flow prioritizes seed development over flesh quality in evolutionary terms. The seed represents the plant’s genetic investment, while the flesh serves primarily to facilitate seed dispersal. Chemical analysis shows that minerals like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium accumulate preferentially in seeds before being redirected to flesh. This priority system means that environmental stresses affecting the tree often impact seed development minimally while reducing fruit size and quality substantially.

Defense compounds concentrate near the stone in many apricot varieties. Cyanogenic glycosides like amygdalin occur at high levels in the seed and endocarp but at much lower levels in outer flesh. When tissue damage occurs, enzymes hydrolyze these compounds releasing hydrogen cyanide. This chemical defense protects the seed from insect predation and pathogen attack. The gradient of defensive compounds from stone to skin reflects evolutionary pressure to protect reproductive structures while maintaining flesh palatability for seed dispersers.

The stone influences water relations and gas exchange in the surrounding tissue. Its impermeability restricts direct water loss from interior regions, creating a moisture gradient across the flesh. Oxygen diffusion inward from the skin slows at the stone boundary, potentially creating zones of lower oxygen that favor fermentative metabolism. In Apricot Fruit Science, the stone is recognized not as an inert structure but as an active interface that shapes chemical conditions in adjacent tissues through physical and chemical properties.

Apricot Fruit Science: Stone Formation and Chemical Partitioning

| Stone-Related Aspect | Chemical and Developmental Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Endocarp Lignification | Phenolic precursors polymerize creating rigid barrier |

| Seed Nutrient Priority | Nitrogen and phosphorus accumulate in embryo before flesh |

| Cyanogenic Compounds | Amygdalin concentration highest in kernel and inner layers |

| Gas Diffusion Barrier | Lignified endocarp limits oxygen penetration to seed cavity |

| Water Impermeability | Stone prevents water exchange between vascular system and seed |

| Evolutionary Function | Flesh chemistry balances palatability with seed protection |

Conclusion: Apricot Fruit Science – What Apricot Reveals About Fruit Chemistry Design

Credit: iken3

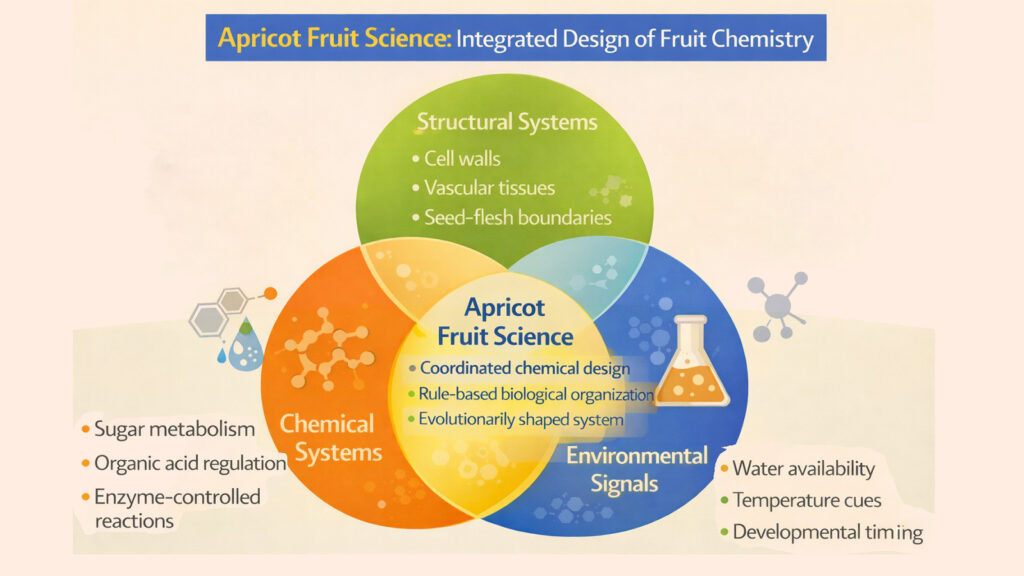

The six chemical systems examined here operate as integrated components of a single biological design. Sugar distribution shapes structural organization by creating osmotic gradients that drive water movement. Water flow delivers minerals and dilutes acids while enabling cell expansion. Organic acids regulate enzyme activities and provide respiratory substrates. Cell wall enzymes remodel tissue architecture in ethylene-driven sequences. Hormone signals coordinate these changes across tissue zones. The stone creates boundaries that partition chemical environments for reproductive versus dispersal functions.

Apricot fruit exposes these relationships with particular clarity because of its modest size, thin skin, and rapid progression through developmental stages. Researchers can sample tissue with fine spatial resolution to map chemical gradients and observe metabolic responses within days. The fruit’s sensitivity to perturbation makes it an informative experimental system. What appears as vulnerability in commercial production becomes advantage in scientific investigation.

The organizing principles visible in apricot apply broadly across stone fruits and beyond. All climacteric fruits coordinate ripening through hormone signaling. The chemical gradients and metabolic sequences found in apricots appear in modified form across diverse species. By studying apricot chemistry in detail, researchers develop frameworks for understanding fruit biology generally.

The Science behind the Apricot Fruit demonstrates that fruit chemistry follows rules shaped by evolutionary pressures and biochemical constraints. Sugar transport maximizes energy delivery to growing fruit. Water regulation balances cell expansion against turgor limits. Controlled softening prepares tissue for consumption while maintaining structure until optimal dispersal timing. The value of apricot as a reference model lies in its transparency. As techniques for analyzing fruit chemistry continue advancing, the apricot will likely maintain its position as a preferred subject for understanding how fruits organize their internal chemistry to fulfill developmental and ecological functions.

Apricot Fruit Science: Integration of Chemical Systems in Fruit Development

| Integrated System | Cross-System Interactions and Coordinated Functions |

|---|---|

| Sugar-Water Coupling | Osmotic potential drives water influx increasing turgor pressure |

| Acid-Enzyme Interaction | Low pH inhibits softening enzymes until ripening raises pH |

| Hormone-Metabolism Link | Ethylene regulates genes for sugar and acid metabolism simultaneously |

| Stone-Flesh Partition | Impermeable endocarp separates seed and flesh chemical zones |

| Environmental Response | Water stress triggers hormone signaling modulating internal chemistry |

| Temporal Coordination | Sequential pathway activation prevents conflicting processes |

Read More Science Articles

- 8 Amazing Citrus Fruits That Will Brighten Your Day

- 8 Incredible Musaceae Fruits You Need to Try Right Now

- Top 8 Delicious Anacardiaceae Fruits You Must Try

- 8 Incredible and Healthy Cucurbitaceae Fruits to Enjoy

- 8 Irresistible Ericaceae Fruits (Heath Family) to Savor and Enjoy

- Explore 8 Amazing Solanaceae Fruits (Nightshade Family) Worth Knowing

- 8 Weird Ways Grapefruit Can Interfere with Medications

- Pomelo in Culture: 8 Heartwarming Ritual Traditions