Table of Contents

Introduction: The Role of the Global Economic Institution in an Accelerating AI Era

Global Economic Institutions form the backbone of international commerce and financial stability. These organizations include the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, World Trade Organization, Asian Development Bank, BRICS New Development Bank, and African Development Bank. They set rules for trade, provide development financing, and coordinate responses to economic crises. Without them, global markets would lack structure and predictability.

These institutions now face unprecedented pressure from artificial intelligence. The technology is not a distant concern anymore. Nearly forty percent of jobs worldwide are exposed to AI, according to recent IMF analysis. This exposure is particularly high in advanced economies where cognitive work dominates. The shift is forcing every Global Economic Institution to rethink how it operates, how it regulates, and how it serves member nations.

AI is already reshaping trade patterns. The WTO projects that universal AI adoption with high productivity growth could boost global trade by nearly fourteen percentage points through 2040. Digitally delivered services may see cumulative growth approaching eighteen percentage points under optimistic scenarios. These are not small changes. They represent fundamental shifts in how countries exchange value and how economies connect.

The technology also brings risks. An AI divide threatens to widen between nations with strong digital infrastructure and those without. The number of quantitative restrictions on AI-related goods has climbed from 130 in 2012 to nearly 500 in 2024. Without coordination, regulatory fragmentation could make cross-border AI commerce increasingly difficult. Global Economic Institutions must modernize quickly or risk irrelevance.

Global Economic Institutions and Their Relationships with Core Building Blocks of the Global Economy

| Building Blocks Of Global Economy | Relationship with Global Economic Institutions |

|---|---|

| Global Economic Governance | Global economic governance sets the rules, norms, and direction for how the Global Economic Institutions like the WTO, IMF, World Bank, and Asian Development Bank act as the operational arms that implement these rules. |

| Global Financial Systems | Global institutions such as the WTO, IMF, World Bank, and Asian Development Bank provide the rules, stability mechanisms, and development support that help global financial systems function smoothly. |

| Global Trade | The WTO sets trade rules and dispute resolution mechanisms while the IMF and World Bank provide trade financing and balance of payments support for member countries |

| Labor Migration | The IMF’s AI Preparedness Index shows 40% of global employment faces AI exposure with Global Economic Institutions now addressing workforce transitions and skill development needs |

| Global Tech Innovation | Development banks including the Asian Development Bank and New Development Bank increasingly finance digital infrastructure while the IMF tracks AI’s productivity impacts across economies |

| Natural Resources and Global Energy | The World Bank and regional development banks fund energy transition projects while AI-driven demand for electricity creates new pressures on power grids and resource allocation |

| Global Supply Chain | The WTO addresses supply chain disruptions through trade facilitation agreements while AI enables predictive logistics and automated customs that require new institutional frameworks |

| Geopolitics | BRICS institutions and traditional multilateral banks reflect competing visions of global economic governance with AI accelerating shifts in institutional influence and power dynamics |

| Demographics | The IMF projects aging populations in economies representing 75% of global output with AI offering potential solutions while creating new inequality challenges |

| Climate and Sustainability | Global Economic Institutions coordinate climate financing and carbon tracking with AI providing enhanced monitoring capabilities but also driving increased energy consumption |

1. How Global Economic Institutions Must Reinvent Decision-Making Through AI

AI-powered forecasting is transforming how every Global Economic Institution makes decisions. The IMF now uses AI tools to classify central bank communications by topic, sentiment, and forward-looking content. This helps the institution understand policy directions faster than traditional analysis allowed. The technology processes vast text datasets almost instantly, revealing patterns that human analysts might miss.

Simulation capabilities have grown equally impressive. AI models can now test how different policy scenarios might unfold across interconnected economies. The World Bank uses these tools to project development outcomes under various intervention strategies. This allows institutions to anticipate consequences before committing resources. The precision remains imperfect, but the improvement over past methods is substantial.

Risk modeling has become more sophisticated. Machine learning techniques outperform traditional statistical methods in predicting sovereign debt crises and currency collapses. Research shows that gradient boosting machines, random forests, and deep learning neural networks achieve higher accuracy than conventional logit models. Some studies report prediction rates approaching ninety percent for crisis detection.

Yet challenges emerge alongside these benefits. Algorithmic bias poses serious risks when AI systems trained on historical data perpetuate existing inequalities. If past lending patterns favored certain countries or demographics, AI models might replicate these biases automatically. Transparency suffers when complex neural networks make decisions through processes that even their designers struggle to explain.

Data asymmetry creates additional problems. Countries with strong statistical systems feed better information into AI models, potentially receiving more favorable assessments. Nations with weak data infrastructure may appear riskier than they actually are, not because of economic fundamentals but because their data quality is poor. This creates a vicious cycle where disadvantaged countries face higher borrowing costs.

Global Economic Institutions must therefore balance AI adoption with human oversight. The technology should augment expert judgment rather than replace it entirely. Institutions need clear governance frameworks that specify when AI recommendations require human review. They must also invest heavily in explaining AI decisions to member countries and the public.

AI Transformation of Decision-Making in Global Economic Institutions

| Decision-Making Area | AI Impact on Global Economic Institutions |

|---|---|

| Crisis Prediction | IMF research shows AI models can identify forty percent of global employment facing AI exposure while machine learning predicts sovereign debt crises with rates exceeding seventy-four percent accuracy |

| Economic Forecasting | The WTO estimates AI could increase global trade by fourteen percentage points by 2040 with digitally delivered services potentially growing eighteen percentage points under optimistic adoption scenarios |

| Policy Simulation | Global Economic Institutions now use AI to model intervention outcomes across multiple economies simultaneously enabling faster testing of policy alternatives before implementation |

| Risk Assessment | Machine learning techniques including random forests and deep learning neural networks outperform traditional statistical methods in detecting financial stress and predicting market dysfunction |

| Resource Allocation | Development banks apply AI to optimize project selection and funding priorities based on predicted development impacts and alignment with sustainable development goals |

| Communication Analysis | The IMF developed AI tools that classify central bank statements by topic, sentiment, and forward-looking content to track policy directions across member countries more efficiently |

| Data Processing | AI enables Global Economic Institutions to analyze unstructured data from reports, news, and social media providing real-time insights into economic conditions beyond official statistics |

| Transparency Challenges | Complex AI models create explainability problems as neural networks make recommendations through processes difficult for experts and member countries to interpret or validate |

2. Why Global Economic Institutions Need AI-Powered Trade and Customs Systems

Trade logistics remain slow and expensive despite decades of digitalization efforts. Documents still pile up at borders. Compliance checks create delays. Small errors trigger rejections. AI offers solutions to these persistent problems. Automated customs clearance systems can process shipments in minutes rather than hours or days.

The technology excels at pattern recognition. AI customs systems scan documents for inconsistencies, flag unusual transactions, and detect potential fraud. The WTO notes that AI can streamline regulatory compliance and help businesses navigate complex trade requirements. This lowers barriers, particularly for small and medium enterprises that lack dedicated compliance teams.

Supply chain mapping becomes more sophisticated with AI. Algorithms track components across multiple borders and predict disruption risks. When a supplier faces problems, AI systems can identify alternative sources before shortages occur. This resilience proved valuable during recent global supply chain crises when traditional tracking methods failed.

Trade fraud detection has improved substantially. Machine learning models identify suspicious patterns in trade data that human analysts might overlook. These systems flag unusual pricing, document mismatches, and routing anomalies. Customs authorities using AI report higher detection rates with fewer false positives than rule-based systems.

However, implementing these systems requires coordination among Global Economic Institutions. The WTO must work with the IMF and development banks to create unified digital trade protocols. Without standardization, each country might deploy incompatible systems. Cross-border transactions would become more complicated rather than simpler.

Standards also need updating. Current trade agreements were written before AI existed. They do not address algorithmic decision-making in customs, data sharing requirements, or liability when AI systems make errors. Global Economic Institutions must develop new frameworks that allow AI adoption while protecting legitimate commercial interests.

The digital divide poses another challenge. Advanced economies can afford sophisticated AI customs systems. Developing nations often lack the infrastructure, technical expertise, and funding to deploy similar capabilities. This creates an uneven playing field. Global Economic Institutions must provide financial and technical assistance to ensure AI benefits reach all member countries.

AI-Powered Trade Systems and Global Economic Institutions

| Trade System Component | Role of Global Economic Institutions |

|---|---|

| Customs Clearance | The WTO identifies AI as a tool to automate border processes and reduce trade costs with institutions needing to establish interoperability standards across national systems |

| Compliance Automation | Global Economic Institutions must develop frameworks for algorithmic compliance checking while ensuring AI systems do not discriminate against businesses from developing countries |

| Supply Chain Mapping | Development banks finance digital infrastructure enabling AI-driven supply chain visibility while the IMF tracks how supply chain resilience affects economic stability |

| Fraud Detection | The WTO notes AI can identify unusual trade patterns and pricing anomalies but institutions must coordinate on data sharing protocols and investigation procedures |

| Document Processing | AI systems reduce paperwork delays at borders but Global Economic Institutions need to standardize document formats and establish cross-border recognition of digital certificates |

| SME Access | The WTO emphasizes AI could level playing fields for small businesses by lowering trade barriers but institutions must ensure technology access does not favor large corporations |

| Infrastructure Investment | The Asian Development Bank and World Bank increasingly fund digital trade infrastructure with AI-related goods trade rising twenty percent annually in the first half of 2025 |

| Regulatory Fragmentation | The number of quantitative restrictions on AI-related goods climbed from 130 in 2012 to nearly 500 in 2024 requiring Global Economic Institutions to prevent further divergence |

3. How Global Economic Institutions Will Adapt to Digital Currencies and Tokenized Finance

Central bank digital currencies are spreading rapidly. As of 2025, 137 countries and currency unions representing ninety-eight percent of global GDP are exploring CBDCs. Three countries have fully launched digital currencies. Forty-nine pilot projects are now underway worldwide. This represents explosive growth from just thirty-five countries exploring CBDCs in May 2020.

CBDCs challenge how Global Economic Institutions think about money. Traditional frameworks assume physical cash and commercial bank deposits. Digital currencies issued directly by central banks create new dynamics. They reduce settlement times, lower transaction costs, and increase financial inclusion. The IMF notes CBDCs can overcome frictions in cross-border payments by reducing intermediaries.

Wholesale CBDC projects have more than doubled since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions. Thirteen cross-border wholesale initiatives now exist, including Project mBridge, which connects banks in China, Thailand, the UAE, Hong Kong, and Saudi Arabia. These systems allow instant international settlement without correspondent banking networks.

The implications for Global Economic Institutions are profound. The IMF must rethink how it monitors capital flows when digital currencies enable near-instant cross-border transfers. Exchange rate surveillance becomes more complex. Currency crises could develop faster when money moves at digital speeds. Traditional balance of payments statistics may not capture these flows adequately.

Blockchain and tokenized assets add further complexity. Assets from real estate to commodities can now be divided into digital tokens and traded globally. This creates new liquidity but also new risks. Global Economic Institutions must develop frameworks for tracking tokenized asset movements and assessing their impact on financial stability.

Anti-fraud systems need updating. Digital currencies enable faster transactions but also faster fraud. Money laundering techniques evolve as criminals exploit new technologies. Global Economic Institutions must coordinate on digital currency monitoring while respecting privacy rights. The balance between surveillance and freedom remains contentious.

Settlement mechanisms require redesign. Traditional international payments move through multiple intermediaries over several days. CBDC platforms promise instant final settlement. But this requires Global Economic Institutions to update treaties, regulations, and technical standards. Legal frameworks written for correspondent banking do not fit CBDC architectures well.

Digital liquidity introduces another variable. When anyone can hold central bank money directly, commercial banks may face deposit flight during crises. This could destabilize financial systems unless Global Economic Institutions develop new liquidity support mechanisms. The World Bank and regional development banks must consider how CBDCs affect their lending operations.

Digital Currency Challenges for Global Economic Institutions

| Digital Finance Area | Institutional Adaptation Requirements |

|---|---|

| CBDC Proliferation | With 137 countries representing 98% of global GDP exploring CBDCs, Global Economic Institutions must coordinate on interoperability standards and cross-border settlement protocols |

| Wholesale Platforms | Thirteen cross-border wholesale CBDC projects including Project mBridge require the IMF and World Bank to update capital flow monitoring and exchange rate surveillance methodologies |

| Settlement Speed | CBDCs enable instant final settlement compared to multi-day correspondent banking requiring Global Economic Institutions to revise treaties and legal frameworks for international payments |

| Financial Stability | Direct central bank digital currency holdings may cause deposit flight from commercial banks during crises forcing institutions to develop new liquidity support mechanisms |

| Capital Flow Tracking | The IMF must develop real-time monitoring capabilities as digital currencies enable near-instant cross-border transfers that traditional balance of payments statistics cannot capture adequately |

| Tokenized Assets | Global Economic Institutions need frameworks for tracking digital asset tokens representing real estate, commodities, and securities as these create new liquidity and systemic risks |

| Anti-Fraud Systems | Digital currency speeds enable faster fraud requiring coordinated monitoring across borders while Global Economic Institutions balance surveillance needs against privacy rights |

| Regulatory Gaps | Current international agreements do not address algorithmic decision-making in digital currency systems or liability when automated settlement systems fail or make errors |

4. How Global Economic Institutions Must Address AI-Driven Market and Debt Risks

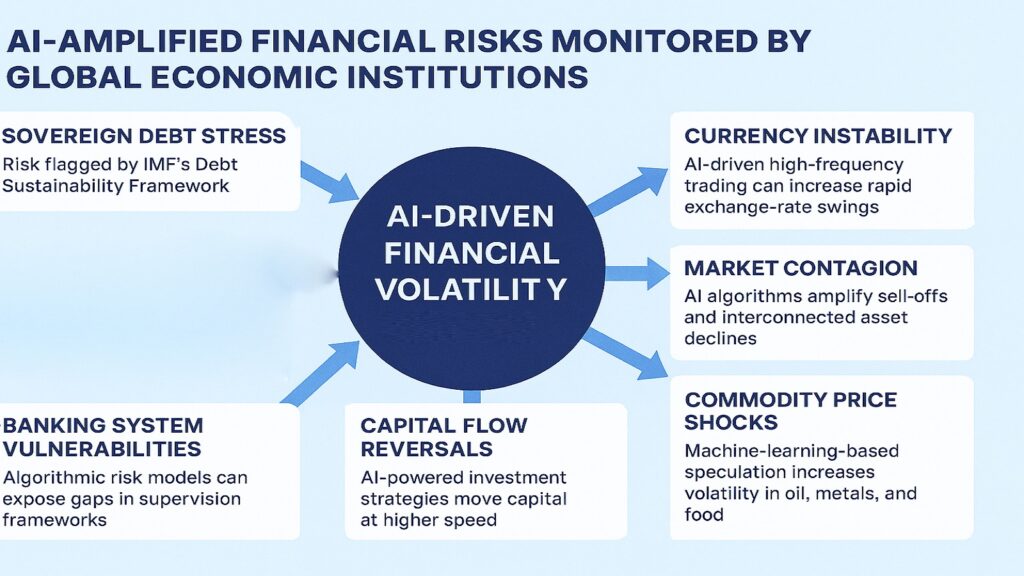

AI is transforming how financial markets operate. Generative AI lowers barriers for quantitative investors to enter less liquid asset classes, including emerging markets and corporate debt. This should improve market liquidity, but also creates new vulnerabilities. When many algorithms respond to the same signals simultaneously, market movements can accelerate dangerously.

The IMF’s October 2024 Global Financial Stability Report examines how AI affects capital markets. Patent filings reveal the scope of change. Since large language models emerged in 2017, AI content in algorithmic trading patent applications has risen from nineteen percent to over fifty percent annually since 2020. A wave of AI-driven trading innovation is building.

Contagion mechanisms may amplify through AI. When algorithms detect stress signals, they might all reduce risk exposure at once. This herd behavior could turn small shocks into major crises. Flash crash events demonstrate the risk. In May 2010, US stock prices collapsed and rebounded within minutes as automated trading algorithms interacted unpredictably.

Sovereign debt monitoring must evolve. Machine learning models can predict debt crises earlier than traditional methods. Research shows that techniques including gradient boosting machines, extreme gradient boosting, and deep learning neural networks achieve superior accuracy. Some studies report crisis prediction rates approaching eighty-nine percent.

However, these AI capabilities also accelerate market reactions to warning signals. When algorithms detect rising debt risks, they might sell sovereign bonds rapidly. This creates self-fulfilling prophecies where algorithmic warnings trigger the very crises they predict. Global Economic Institutions must manage this feedback loop carefully.

Currency crises could develop with unprecedented speed. AI monitors economic indicators continuously and executes trades in milliseconds. Traditional early warning systems gave policymakers days or weeks to respond. AI-driven markets may leave only hours. The IMF must develop rapid multilateral response mechanisms that match AI trading speeds.

Debt sustainability assessments require rethinking. AI models excel at identifying complex patterns in economic data. They can predict which countries face heightened default risks even when traditional indicators appear stable. But these predictions may become public quickly through leaked models or reverse engineering. Global Economic Institutions must consider how algorithmic risk assessment affects market confidence.

Coordinated responses become more critical. When an AI-detected crisis threatens to spread, Global Economic Institutions must act faster than ever. The IMF, World Bank, and regional development banks need pre-agreed protocols for rapid coordination. Deliberate committee processes that worked in slower times may prove inadequate.

AI-Driven Financial Risk Management by Global Economic Institutions

| Risk Category | AI Impact and Institutional Response |

|---|---|

| Algorithmic Trading | AI content in algorithmic trading patents rose from 19% in 2017 to over 50% since 2020 requiring Global Economic Institutions to monitor for coordinated algorithm behavior |

| Market Contagion | AI-driven herd behavior may amplify small shocks into major crises as algorithms simultaneously reduce risk exposures forcing institutions to develop faster crisis detection systems |

| Sovereign Debt Prediction | Machine learning models including gradient boosting and neural networks predict debt crises with accuracy approaching 89% enabling earlier warnings but also risking self-fulfilling market reactions |

| Currency Crisis Speed | AI monitors economic indicators continuously and executes trades in milliseconds reducing response time from days to hours requiring rapid multilateral coordination protocols |

| Liquidity Dynamics | Generative AI enables quantitative investors to enter emerging market debt and other less liquid assets improving liquidity but creating new concentration risks |

| Flash Crash Events | Unpredictable interactions between trading algorithms caused the 2010 flash crash demonstrating how automated systems can destabilize markets requiring better volatility response mechanisms |

| Early Warning Systems | The IMF must develop AI-enhanced surveillance that matches market speeds while coordinating with World Bank and regional development banks on rapid response protocols |

| Risk Assessment Feedback | When AI models predict elevated default risks, markets may react before fundamentals deteriorate creating feedback loops that Global Economic Institutions must manage carefully |

5. How Global Economic Institutions Will Redefine Development Models in an AI Economy

Traditional development financing focused on physical infrastructure. Roads, ports, power plants, and irrigation systems dominated lending portfolios. These remain important but insufficient. The AI era demands different priorities. Digital infrastructure, cloud ecosystems, data governance, and workforce reskilling now matter as much as bridges and dams.

The shift is already visible. Global AI data center investment reached fifty-seven billion dollars in 2024, with emerging markets capturing growing shares. Latin America expects over two billion dollars in data center investment for 2024 alone, with the regional market projected to double from six billion dollars in 2023 to ten billion dollars by 2029.

Asia shows similar patterns. India’s digital infrastructure investment is accelerating to address rapid data consumption growth. Small cell networks and fiber deployments present scalable opportunities. China has become predominantly urban, with sixty-seven percent of its population in cities. Smart city AI applications in Shanghai and Shenzhen are transforming urban management and public services.

The New Development Bank, established by BRICS countries, is incorporating AI into its operations. The bank uses advanced technology for lean management while financing sustainable infrastructure. It has signed cooperation agreements with the Asian Development Bank on renewable energy, clean transportation, and sustainable water management. AI applications help optimize these investments.

Workforce reskilling represents a critical challenge. The IMF estimates AI exposure affects forty percent of global employment, with older workers potentially less able to adapt. Advanced economies must focus on upgrading regulatory frameworks and supporting labor reallocation. Developing nations need to prioritize digital infrastructure and digital skills development first.

Data governance frameworks require institution-building support. Countries need legal structures for data privacy, cross-border data flows, and algorithmic accountability. Global Economic Institutions must help developing nations build these capabilities. Without them, countries cannot participate fully in the digital economy or protect their citizens adequately.

Cloud infrastructure differs fundamentally from physical infrastructure. It requires continuous investment rather than one-time construction. Operating costs remain high. Cybersecurity demands constant vigilance. Global Economic Institutions must adapt financing models to support recurring technology expenses rather than just capital expenditures.

Digital divides risk widening. The IMF’s AI Preparedness Index shows that wealthier economies are better equipped for AI adoption than low-income countries. Infrastructure gaps combine with workforce skill deficits and weak regulatory capacity. Without coordinated support from Global Economic Institutions, technological inequality will deepen economic inequality.

Development Priorities for Global Economic Institutions in the AI Era

| Development Area | AI-Era Requirements for Global Economic Institutions |

|---|---|

| Digital Infrastructure | Global AI data center investment reached $57 billion in 2024 with the Asian Development Bank and World Bank needing to finance fiber networks, cloud platforms, and edge computing |

| Workforce Reskilling | IMF analysis shows 40% of global employment faces AI exposure requiring Global Economic Institutions to fund technical training and support labor market transitions |

| Data Governance | Countries need legal frameworks for data privacy and cross-border flows with development banks providing capacity building for digital regulation and algorithmic accountability |

| Cloud Ecosystems | Unlike physical infrastructure requiring one-time construction, cloud platforms need continuous investment forcing Global Economic Institutions to develop new recurring financing models |

| Urban AI Systems | China’s smart cities in Shanghai and Shenzhen use AI for traffic management and public services with regional development banks helping other countries deploy similar capabilities |

| Small Cell Networks | India’s rapid data consumption growth drives fiber and small cell investment presenting opportunities for the Asian Development Bank to finance emerging digital infrastructure |

| Digital Divide | The IMF’s AI Preparedness Index shows wealthier economies better equipped for AI adoption requiring coordinated institution support to prevent technological inequality from deepening |

| Technical Capacity | Developing nations need digital skills, regulatory expertise, and cybersecurity capabilities forcing Global Economic Institutions to shift from hardware financing toward institutional capacity building |

6. How Global Economic Institutions Must Navigate Power Shifts in an AI-Dominated World

AI accelerates geopolitical realignments. Countries that master the technology gain economic and strategic advantages. Those that fall behind risk marginalization. This dynamic is shifting influence among Global Economic Institutions as nations seek platforms that serve their interests better.

BRICS expansion reflects these shifts. The bloc added several members in 2024 and invited thirteen countries as partners. Indonesia became the first Southeast Asian member in January 2025. The expansion strengthens BRICS as a representative of the Global South. It creates alternatives to Western-dominated institutions.

The New Development Bank exemplifies emerging institutional power. Established with fifty billion dollars in initial subscribed capital, the bank now has an expanding membership beyond the original BRICS nations. Algeria gained membership status in September 2024. The bank’s authorized capital of one hundred billion dollars rivals some traditional development banks.

AI cooperation among BRICS nations is nascent but growing. The 2023 BRICS Summit committed to establishing a BRICS AI Study Group and Digital Economy Working Group. Member countries recognize that collective AI policy development can counter Western technology dominance. The New Development Bank invests in AI applications across member nations.

China’s digital currency provides another example. The e-CNY remains technically in a pilot stage, but consumers have created 2.25 billion digital wallets. China also participates in Project mBridge for cross-border CBDC transactions. This infrastructure could reduce dependence on dollar-based payment systems over time.

Traditional Global Economic Institutions face legitimacy questions. Voting structures in the IMF and World Bank reflect post-World War II power dynamics. Emerging economies argue their economic weight justifies greater influence. AI’s tendency to concentrate in technology leaders may intensify these demands.

Representation must evolve. Countries contributing more to global GDP and hosting more AI development should arguably hold more institutional sway. But reforming governance structures proves politically difficult. Existing powers resist dilution of their influence even as economic realities shift beneath them.

Collaboration models need updating. Competition between traditional and emerging Global Economic Institutions could fragment the international system. Better outcomes require cooperation. The New Development Bank’s memorandums of understanding with the Asian Development Bank and cooperation on sustainable development show pathways forward.

Geopolitical Shifts Affecting Global Economic Institutions

| Power Shift Dimension | Implications for Global Economic Institutions |

|---|---|

| BRICS Expansion | The bloc added members in 2024 and invited thirteen countries as partners with Indonesia joining in January 2025 strengthening alternatives to Western-dominated institutions |

| New Development Bank Growth | Established with $50 billion in subscribed capital and $100 billion authorized capital, the bank now extends beyond original BRICS members with Algeria joining in September 2024 |

| Digital Currency Infrastructure | China’s e-CNY pilot created 2.25 billion digital wallets with participation in Project mBridge potentially reducing dollar-based payment system dependence over time |

| AI Cooperation Frameworks | BRICS committed to establishing AI Study Group and Digital Economy Working Group in 2023 enabling collective policy development to counter Western technology dominance |

| Voting Structure Reform | Emerging economies argue their GDP contributions and AI development justify greater influence in IMF and World Bank governance though reforms prove politically difficult |

| Institutional Legitimacy | Post-World War II power dynamics embedded in traditional Global Economic Institutions face challenges as economic weight shifts toward Asia and the Global South |

| Technology Concentration | AI development concentrates in few countries intensifying demands for governance reforms as technology leaders gain disproportionate economic and strategic advantages |

| Cooperation Opportunities | The New Development Bank’s memorandums with the Asian Development Bank on sustainable development show how traditional and emerging institutions can collaborate effectively |

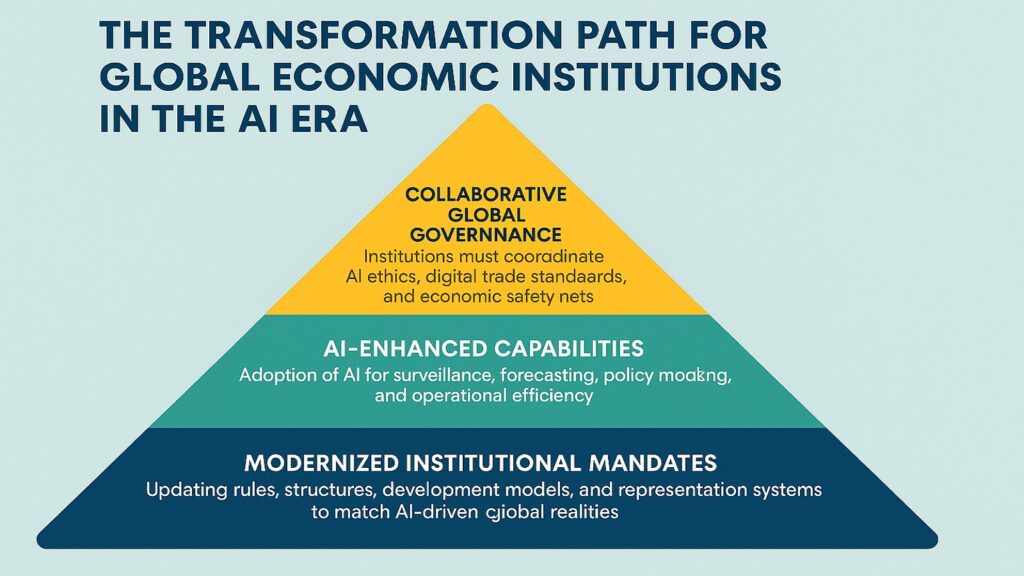

Conclusion: Why the Global Economic Institution Must Transform to Stay Relevant in the AI Era

Global Economic Institutions stand at a crossroads. They can embrace AI-driven transformation and remain central to international commerce and development. Or they can resist change and watch influence shift to new institutions built for digital economies. The choice should be obvious, but implementation remains difficult.

The six urgent shifts outlined here are interconnected. AI-powered decision-making enables better crisis prediction but also faster market reactions. Digital currencies improve cross-border payments but challenge traditional monetary surveillance. Development priorities must evolve toward digital infrastructure while managing workforce transitions. Trade systems need AI automation, but also require coordinated standards.

Speed matters enormously. AI adoption is accelerating across economies. The WTO projects trade could grow by fourteen percentage points by 2040 under universal AI adoption. But this assumes institutions create supportive frameworks. If Global Economic Institutions lag, they risk becoming obstacles rather than enablers.

Coordination is equally critical. No single institution can address AI’s implications alone. The IMF must work with the World Bank on development financing. The WTO needs cooperation from regional banks on trade infrastructure. BRICS institutions and traditional multilateral banks must find collaborative approaches despite competing visions.

The AI divide poses the gravest risk. Technology’s benefits could flow primarily to advanced economies and large corporations. Developing nations might face higher borrowing costs, more volatile markets, and fewer development opportunities. Global Economic Institutions must actively prevent this outcome through targeted support and inclusive governance.

Yet AI also offers unprecedented opportunities. Enhanced forecasting could prevent crises before they escalate. Automated trade systems could integrate developing countries into global markets. Digital currencies might provide financial services to billions currently excluded. Development could accelerate dramatically if institutions deploy resources intelligently.

Transformation requires courage. Established institutions resist change. Powerful members protect their privileges. But the alternative is institutional decline. Global Economic Institutions that fail to evolve will see their relevance diminish as nimbler organizations rise to meet AI-era needs.

The path forward demands innovation, flexibility, and inclusivity. Every Global Economic Institution must experiment with new approaches while maintaining stability. They must embrace technological tools while exercising human judgment. Most importantly, they must ensure AI strengthens global cooperation rather than fractures it.

Critical Success Factors for Global Economic Institutions in the AI Era

| Success Factor | Requirements for Global Economic Institutions |

|---|---|

| Decision-Making Transformation | Institutions must deploy AI for forecasting and risk assessment while maintaining human oversight and addressing algorithmic bias and transparency challenges |

| Trade System Modernization | The WTO must coordinate with IMF and development banks to create unified digital trade protocols while closing infrastructure gaps in developing countries |

| Digital Currency Frameworks | Global Economic Institutions need updated treaties for CBDC interoperability, capital flow monitoring, and anti-fraud systems that balance surveillance with privacy rights |

| AI Risk Management | The IMF and World Bank must develop rapid coordination protocols matching AI trading speeds while managing self-fulfilling prophecy risks in debt and currency markets |

| Development Model Evolution | Institutions must shift from physical to digital infrastructure financing while supporting workforce reskilling and data governance capacity in developing nations |

| Governance Reform | BRICS expansion and AI concentration require updating voting structures and representation in traditional institutions while maintaining cooperation across competing platforms |

| Speed of Adaptation | AI adoption accelerates across economies with WTO projecting 14 percentage point trade growth by 2040 requiring institutions to transform rapidly or risk irrelevance |

| Coordinated Response | No single institution addresses AI implications alone requiring IMF, World Bank, WTO, and regional banks to collaborate despite institutional competition and differing mandates |