Table of Contents

Introduction: Why Natural Resources Still Shape the Heart of Global Trade

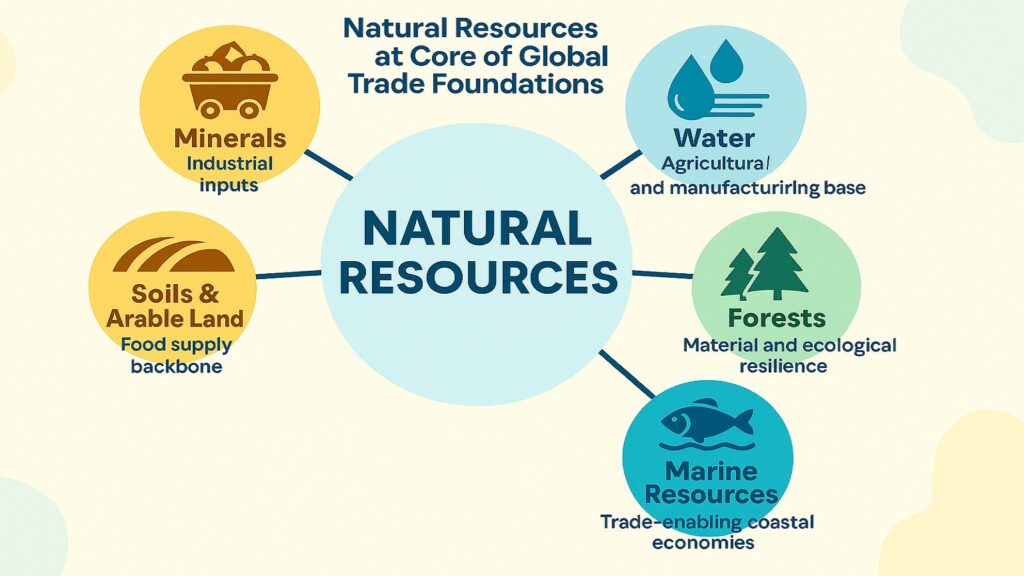

The world moves fast toward digital currencies and artificial intelligence, yet beneath the screens and algorithms lies something older and more enduring. Natural resources remain the foundational building blocks of the global economy. Every smartphone requires rare earth minerals. Every factory needs water and energy. The physical world of minerals, forests, soils, and freshwater still anchors production in ways that technology cannot replace.

Geography determines destiny in global trade more than many realize. The nations that control copper deposits negotiate differently than those without. Countries rich in arable land export food and gain leverage. Those lacking fresh water sources must import or innovate. This uneven distribution creates winners and losers before the first contract gets signed. Supply chains bend around resource availability. Bargaining power flows to those who possess what others need.

The coming decades will see this influence deepen rather than fade. Climate pressures increase water scarcity. Manufacturing demands rare materials in rising quantities. Agricultural productivity depends on soil health and rainfall patterns. As populations grow and consumption expands, the strategic value of natural resources intensifies. Nations recalculate their positions. Companies redesign supply chains. Trade routes shift to follow new resource discoveries or respond to depleting reserves.

Understanding how natural resources reshape global trade requires examining specific mechanisms. Six powerful shifts stand out as particularly consequential. Each represents a distinct way that resource geography influences trade patterns, economic power, and international relationships. Together, they reveal why natural resources will continue to determine which nations prosper and which struggle in global commerce.

How Natural Resources Connect to Other Building Blocks of the Global Economy

| Building Blocks Of Global Economy | Relationship to Natural Resources |

|---|---|

| Global Trade | Natural resources form the physical foundation of international commerce, determining what nations can export and what they must import |

| Labor Migration | Extraction of natural resources and processing industries create employment patterns that influence where workers migrate and how economies develop |

| Tech Innovation | Advanced technologies depend on specific minerals and materials, while innovation helps discover and extract resources more efficiently |

| Global Financial Systems | Prices and availability of natural resources affect currency values, investment flows, and financial market stability across borders |

| Governance and Institutions | Resource management requires regulatory frameworks, international agreements, and institutional capacity to prevent conflicts |

| Global Supply Chain | Manufacturing and distribution networks organize around resource availability, affecting factory locations and logistics infrastructure |

| Geopolitics | Control over strategic resources shapes diplomatic relationships, security alliances, and the balance of power between nations |

| Demographics | Population distribution and growth patterns depend on access to water, arable land, and other resources that sustain settlements |

| Climate and Sustainability | Resource extraction drives environmental impacts, while climate change affects resource availability and distribution |

1. How Natural Resources Redirect Global Trade Routes

Trade routes emerge where natural resources concentrate. The Silk Road connected Chinese silk to Mediterranean markets. European ships crossed oceans seeking spices and precious metals. American railroads followed mineral deposits westward. Today, the pattern continues with modern infrastructure. Ports expand near oil terminals and mineral export facilities. Railways stretch across continents to move coal and iron ore. Maritime shipping lanes adjust based on changing resource flows.

The Arctic presents a contemporary example of route redirection driven by natural resources. Melting ice opens new shipping passages between Asia and Europe. These northern routes reduce travel time compared to traditional paths through the Suez Canal. But resource access drives the interest more than speed alone. The Arctic holds substantial reserves of oil, natural gas, and minerals. Russia develops northern ports to export these natural resources. China invests in Arctic shipping capabilities. A trade route emerges from the magnetic pull of resource wealth beneath ice and rock.

Africa demonstrates how resource discoveries redirect continental trade infrastructure. Oil fields in East Africa prompted new pipeline projects and port expansions. Tanzania and Kenya invested in transportation corridors to move petroleum to international markets. Mineral discoveries in Central Africa led to railway rehabilitation connecting mines to coastal export points. The Democratic Republic of Congo’s copper and cobalt reserves attract infrastructure investment. These projects create new trade arteries that previously did not exist or had fallen into disrepair.

Water resources shape regional trade patterns in ways less visible but equally powerful. The Mekong River system influences trade relationships among Southeast Asian nations. Countries downstream depend on water flow controlled by upstream neighbors. India’s river systems affect its internal trade efficiency and regional geopolitical relationships. Water scarcity in Central Asia forces nations to negotiate over shared resources, affecting broader trade cooperation.

Natural resource depletion redirects established trade routes just as new discoveries create them. North Sea oil production decline changes European energy import patterns. Timber scarcity in Southeast Asia shifts furniture manufacturing to South America and Africa. Soil degradation in some agricultural regions moves food production to areas with better land preservation. These shifts happen gradually but reshape global trade geography over time.

How Natural Resources Influence Major Trade Route Development

| Resource Type | Impact on Trade Infrastructure |

|---|---|

| Mineral Deposits | Drive development of railways, roads, and port facilities connecting extraction sites to international markets |

| Energy Resources | Shape pipeline networks, shipping lanes, and storage facilities that move oil, gas, and coal across borders |

| Freshwater Systems | Determine internal trade efficiency and create dependencies between nations sharing river basins and aquifers |

| Timber and Forests | Influence logging roads, processing center locations, and export terminal development in resource-rich regions |

| Arable Land | Affect agricultural export infrastructure including grain terminals, refrigerated transport, and specialized shipping |

| Marine Resources | Guide fishing fleet harbors, processing facilities, and seafood distribution networks along coastal areas |

2. How Natural Resources Create Unequal Power and Leverage Among Nations

The distribution of natural resources creates asymmetry in international negotiations before discussions begin. Saudi Arabia enters energy talks with different leverage than Japan. Brazil negotiates agricultural trade with advantages that South Korea lacks. Australia possesses mineral wealth that gives it options other nations cannot access. Those with abundant natural resources can afford patience. Those needing imports must accept less favorable terms or find alternative suppliers.

The rare earth minerals situation illustrates this power dynamic clearly. China controls substantial portions of global rare earth production and processing capacity. These materials prove essential for electronics, renewable energy systems, and military applications. This position allows China to influence global supply chains and manufacturing locations. The United States and European countries invest in developing alternative sources, but such efforts require years and substantial capital. Meanwhile, China’s resource position provides ongoing diplomatic and economic leverage.

Resource scarcity forces nations into vulnerable positions despite economic strength otherwise. Japan maintains advanced manufacturing capabilities and financial resources but lacks domestic energy and mineral supplies. This dependency requires careful diplomatic relationships with resource exporters. Germany faces similar constraints regarding energy imports. Both nations must balance economic interests with supply security concerns. Yet the fundamental asymmetry remains. Resource scarcity limits bargaining power regardless of technological sophistication or financial wealth.

Some nations leverage natural resources strategically to achieve broader objectives. Russia uses natural gas exports to maintain influence in European markets. Gulf states employ oil production capacity to affect global prices. Bolivia’s lithium reserves provide negotiating power with countries pursuing electric vehicle production. These resource-rich nations can impose conditions or limit exports to advance national interests. Resource-poor countries rarely possess equivalent options.

Middle-income countries with significant resource endowments gain opportunities that service-based economies cannot access. Indonesia’s nickel reserves attract electric vehicle battery investments. Chile’s copper production provides stable export revenues. Brazil’s agricultural land supports major food export industries. These advantages translate into better trade terms, increased foreign investment, and stronger negotiating positions. The natural resources themselves become diplomatic assets that open doors and create partnerships.

How Natural Resources Create Bargaining Power Differences

| Power Dynamic | Effect on Global Trade Relations |

|---|---|

| Resource Abundance | Enables nations to set terms, influence prices, and secure favorable trade agreements with importing countries |

| Resource Dependency | Forces importing nations to accept less favorable conditions and maintain careful diplomatic relationships |

| Supply Concentration | Allows controlling nations to leverage market position for diplomatic and economic objectives beyond trade |

| Alternative Access | Determines whether dependent nations can diversify suppliers or must accept monopolistic supplier conditions |

| Strategic Reserves | Provides buffer against supply disruptions and reduces vulnerability to supplier pressure tactics |

| Processing Capacity | Concentrates value-added activities and creates additional leverage beyond raw material possession |

3. How Natural Resources Restructure Global Supply Chains

Manufacturing networks organize around resource availability more than companies often acknowledge publicly. A smartphone contains dozens of minerals sourced from multiple continents. An automobile requires steel, aluminum, copper, and increasingly lithium from diverse locations. These dependencies force companies to structure supply chains around resource geography rather than optimal business logistics alone. Factories locate near key inputs. Transportation networks connect resource sources to production facilities across thousands of miles.

The electric vehicle battery industry demonstrates this restructuring clearly. Lithium, cobalt, nickel, and graphite come from different regions with distinct supply chain challenges. Chilean and Australian lithium reaches processing facilities in China where battery cell production concentrates. Cobalt from the Democratic Republic of Congo flows through complex trading networks. Nickel production in Indonesia attracts refining investments. Tesla, BMW, and Toyota all restructure procurement relationships based on where these minerals exist and can be reliably sourced. The resource geography dictates supply chain architecture more than corporate preferences.

Water availability increasingly influences industrial location decisions as scarcity intensifies. Semiconductor manufacturing requires enormous water quantities for cleaning and cooling processes. Taiwan’s dominant chip production faces water constraints during droughts. This prompts companies and governments to consider diversifying production to water-abundant regions. Similarly, textile and chemical industries consume substantial water resources. As water stress increases globally, supply chains must adapt to ensure adequate supplies or risk production disruptions.

Agricultural supply chains constantly adjust to land degradation, climate variability, and soil health changes. Coffee production shifts to higher elevations as traditional growing regions become less suitable. Wheat sourcing diversifies as weather patterns affect traditional breadbasket regions. Palm oil expansion into new territories creates new trade flows and processing centers. Companies that depend on agricultural commodities must continuously evaluate sourcing strategies based on where crops grow successfully.

Timber and forest products demonstrate similar dynamics. As Southeast Asian forests declined, furniture production shifted toward suppliers in South America, Africa, and sustainable northern forests. Paper manufacturers adjusted fiber sources based on forest management practices and availability. These resource-driven shifts affect factory investments, employment patterns, and trade relationships across continents. Supply chains follow the resources regardless of established business relationships.

How Natural Resources Drive Supply Chain Configuration

| Resource Constraint | Supply Chain Response |

|---|---|

| Mineral Scarcity | Forces diversification of sourcing, investment in alternative deposits, and development of recycling capabilities |

| Water Stress | Prompts relocation of water-intensive industries to regions with adequate supplies and better availability |

| Soil Degradation | Shifts agricultural production to areas with healthier land and drives investment in restoration technologies |

| Forest Depletion | Redirects timber sourcing to sustainable forests and encourages material substitution in manufacturing |

| Energy Access | Influences location of energy-intensive industries near reliable power sources and affordable fuel supplies |

| Transport Costs | Affects where bulk resources get processed and whether value-added activities occur near extraction |

4. How Natural Resources Influence Trade Policies and Strategic Alliances

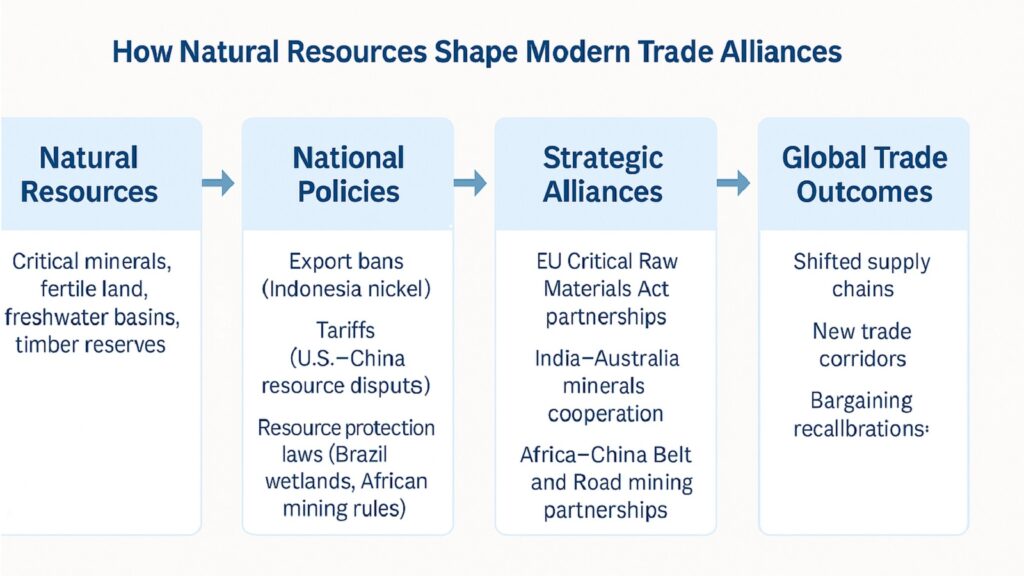

Governments design trade policies around resource security more than free market principles often suggest. Export restrictions on critical minerals protect domestic industries and maintain leverage. Import tariffs shield nascent resource processing capabilities from foreign competition. Subsidies support domestic extraction even when international sources cost less. These policies reflect strategic thinking about long-term resource access. Nations that depend on imports create policies to secure stable supplies. Those with resource wealth craft policies to maximize value and maintain control.

The European Union’s approach to critical raw materials illustrates policy-driven resource security. The EU maintains limited domestic mineral production but requires substantial imports for manufacturing and energy transitions. European policies encourage diversified sourcing, investment in processing capacity, and partnerships with resource-rich nations. Trade agreements increasingly include provisions ensuring reliable access to minerals and materials. These policies aim to reduce dependency on any single supplier while securing necessary inputs for European industries.

The Indian economy is not completely self-reliant on minerals. Its fertilizer policies demonstrate how resource constraints shape domestic regulations. India produces limited phosphate and potassium domestically but needs these nutrients for agricultural productivity. Government policies include import subsidies, strategic stockpiling, and partnerships with suppliers in Russia, Morocco, and Jordan. Trade agreements with these nations often emphasize fertilizer access alongside other economic considerations. The resource need drives policy choices that affect broader trade relationships.

Export restrictions represent another policy tool tied to resource strategy. Indonesia periodically limits nickel ore exports to encourage domestic processing and capture more value. Argentina and Chile discuss lithium export policies that prioritize local industry development. These restrictions force international companies to invest locally rather than simply extracting raw materials. Companies that want access must accept host country terms including technology transfer and local employment.

Regional trade agreements increasingly feature resource cooperation frameworks. The African Continental Free Trade Area includes provisions for mineral value chains and resource sharing. ASEAN discussions address water management and timber trade. South American nations negotiate around energy resources and agricultural coordination. These agreements recognize that resource interdependence requires structured cooperation beyond simple tariff reduction. Nations pool natural resources, coordinate extraction policies, and share processing capabilities.

How Natural Resources Shape Trade Policy Priorities

| Policy Approach | Strategic Resource Objective |

|---|---|

| Export Restrictions | Protect domestic supplies, encourage local processing, and maximize value capture from resource endowments |

| Import Diversification | Reduce dependency on single suppliers and create competitive markets that lower costs and increase security |

| Strategic Stockpiling | Buffer against supply disruptions and provide leverage during price negotiations with international suppliers |

| Investment Treaties | Secure long-term access through ownership stakes and development partnerships in resource-producing regions |

| Processing Requirements | Force value-added activities domestically to create employment and capture economic benefits beyond extraction |

| Regional Cooperation | Pool natural resources across borders and create integrated supply chains that benefit multiple nations simultaneously |

5. How Natural Resources Drive Competition for Critical Raw Materials

The scramble for critical materials intensifies as traditional supplies prove insufficient for rising demand. Copper production struggles to meet electrification needs. Lithium extraction cannot keep pace with battery requirements. Rare earth processing remains concentrated despite diversification efforts. Timber supplies tighten as forests face sustainability pressures. Fertile soil becomes scarcer through degradation and urbanization. This growing gap between supply and demand transforms these natural resources into focal points of international competition.

The lithium situation exemplifies this dynamic. Electric vehicle adoption accelerates globally, driven by climate policies and consumer preferences. Battery production requires substantial quantities of lithium. Current extraction and processing capacity falls short of projected needs. This creates fierce competition for existing supplies and exploration of new deposits. Chile, Australia, and Argentina hold major reserves but face environmental constraints and infrastructure limitations. China dominates processing despite limited domestic reserves. Western nations invest aggressively in alternative sources, including the United States, Canada, and African countries. The competition affects market prices, investment priorities, and diplomatic relationships.

Copper competition follows similar patterns driven by different forces. Electrical infrastructure, renewable energy systems, and construction all require significant copper inputs. Global production concentrates in Chile, Peru, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. New mine development faces environmental opposition and declining ore grades. This tightening market prompts countries to secure long-term supply agreements and invest in exploration. The competition extends beyond commercial considerations into strategic planning about industrial capacity.

Agricultural land represents another arena of increasing competition though less visibly than minerals. Population growth and dietary changes increase food demand while arable land expands slowly if at all. Water scarcity limits productivity in many regions. Soil degradation reduces yields. These pressures push nations and corporations to secure productive land through purchases, leases, and partnerships. Chinese companies acquire farmland in Africa and South America. Middle Eastern nations invest in agricultural projects abroad.

Freshwater competition intensifies as stress increases across regions. India faces groundwater depletion. The Middle East depends on desalination and limited aquifers. Central Asian countries dispute river allocations. These water challenges affect industrial location decisions, agricultural productivity, and urban growth patterns. Nations that control abundant freshwater resources gain advantages in attracting investment. Those facing scarcity must invest in efficiency, alternative sources, or accept constraints on growth.

How Competition for Natural Resources Affects Global Markets

| Critical Resource | Competitive Dynamic and Market Impact |

|---|---|

| Battery Minerals | Intense competition drives prices higher, spurs investment in new deposits, and creates dependencies for vehicle industries |

| Copper and Base Metals | Manufacturing and infrastructure needs exceed production growth, tightening markets and incentivizing recycling |

| Rare Earth Elements | Concentrated processing capacity creates bottlenecks despite distributed deposits, forcing supply chain diversification |

| Timber Resources | Sustainability concerns limit harvests while construction demand grows, pushing prices up and encouraging alternatives |

| Arable Land | Population pressure and dietary changes increase competition for productive farmland and influence food trade patterns |

| Freshwater Access | Growing scarcity affects industrial location choices and creates dependencies that influence broader economic relationships |

6. How Natural Resources Accelerate the Rise of New Regional Trade Blocs

Nations increasingly form coalitions around shared resource strengths and vulnerabilities. These groupings recognize that resource security requires cooperation beyond traditional alliances. Countries with complementary endowments pool strengths. Those facing similar scarcities coordinate responses. Regional blocs emerge that reshape trade patterns and create new centers of economic power. Resource geography and economic necessity drive these formations.

South American nations demonstrate this trend through lithium and copper cooperation. Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia hold substantial lithium reserves concentrated in the Lithium Triangle region. Rather than competing purely against each other, these nations discuss coordination on production levels, processing investments, and market strategies. Peru and Chile cooperate on copper markets despite competitive pressures. Brazil’s agricultural strength complements mineral wealth elsewhere on the continent. These resource-based relationships create trade preferences and investment flows that strengthen regional integration.

African resource coordination emerges gradually but with increasing significance. The African Continental Free Trade Area emphasizes mineral value chains and resource processing. Nations recognize that selling raw materials without capturing processing value limits development potential. Cooperation frameworks encourage regional supply chains where extraction in one country connects to processing in another and manufacturing in a third. The Democratic Republic of Congo’s minerals might process in South Africa and manufacture in Kenya. This integration creates trade flows that previously moved primarily to distant continents.

Southeast Asian nations coordinate around water resources, agricultural commodities, and timber supplies. The Mekong River system creates natural interdependencies that formal cooperation structures acknowledge. ASEAN frameworks address resource management alongside traditional trade issues. Countries balance competitive interests with recognition that shared resource challenges require collective approaches. Palm oil producers coordinate on sustainability standards. These coordinated approaches affect global commodity markets and trade relationships with outside powers.

Middle Eastern energy cooperation extends beyond OPEC’s traditional oil focus. Gulf states invest in renewable energy partnerships that share solar resources and technological capabilities. Water desalination projects involve multiple nations pooling resources and expertise. Natural gas pipeline networks create regional interdependencies. These developments transform Middle Eastern trade patterns from purely outward-facing energy exports toward more integrated regional markets.

How Natural Resources Enable Regional Trade Bloc Formation

| Regional Grouping | Resource-Based Integration Strategy |

|---|---|

| South American Bloc | Coordinates mineral extraction and processing to maximize value capture and strengthen negotiating power |

| African Integration | Develops regional value chains connecting resource extraction to processing and manufacturing within the continent |

| Southeast Asian Framework | Manages shared water systems, coordinates agricultural production, and aligns sustainability approaches |

| Gulf Cooperation | Expands beyond oil to encompass renewable energy, water technology, and integrated infrastructure investments |

| Central Asian Partnership | Addresses shared water challenges and coordinates energy exports while managing competing national interests |

| Pacific Alliance | Combines mineral wealth with agricultural strength to create complementary trade relationships and investment flows |

Conclusion: Why Natural Resources Will Keep Redrawing Global Trade’s Future

The patterns persist even as technology advances and economic systems evolve. Natural resources still determine who trades with whom and on what terms. The nations that control copper, lithium, and rare earths hold leverage in manufacturing. Those with abundant water and arable land dominate food production. Countries possessing energy resources influence global prices and supply security. This fundamental reality transcends temporary market conditions or political arrangements.

Looking forward, resource influence will likely intensify rather than diminish. Climate change affects water availability and agricultural productivity unpredictably. Energy transitions require massive mineral quantities that current extraction cannot satisfy. Population growth increases demand while environmental constraints limit supply expansion. Geopolitical tensions disrupt established supply chains and force reconsideration of dependencies. These pressures magnify the strategic importance of natural resources. Nations that secure reliable access gain economic resilience. Those facing scarcity must adapt quickly or accept diminished prospects

Global trade’s future will be written partly through technological progress and policy choices. But deeper currents flow from resource availability and the competition to secure essential materials. Understanding these dynamics helps anticipate which nations rise, which industries thrive, and where trade flows intensify. Natural resources shaped human commerce when caravans crossed deserts. They shape it now as container ships cross oceans. They will continue shaping it as new industries emerge and old certainties fade.

How Natural Resources Will Shape Future Global Trade Evolution

| Future Dimension | Resource-Driven Transformation |

|---|---|

| Climate Adaptation | Water scarcity and agricultural shifts will redirect food trade and create new dependencies between regions |

| Energy Transition | Mineral requirements for renewable systems will intensify competition and create new resource-based power structures |

| Supply Chain Resilience | Companies will prioritize resource security over cost efficiency, reshaping manufacturing locations and partnerships |

| Regional Integration | Resource cooperation will drive new trade blocs that challenge traditional economic alliances and power centers |

| Technological Development | Innovation will partly depend on access to critical materials, creating advantages for resource-secure nations |

| Diplomatic Priorities | Resource access will increasingly dominate foreign policy as scarcity pressures mount and alternatives remain limited |