Table of Contents

Introduction: The Enduring Power of Overcoming The Monster in Storytelling

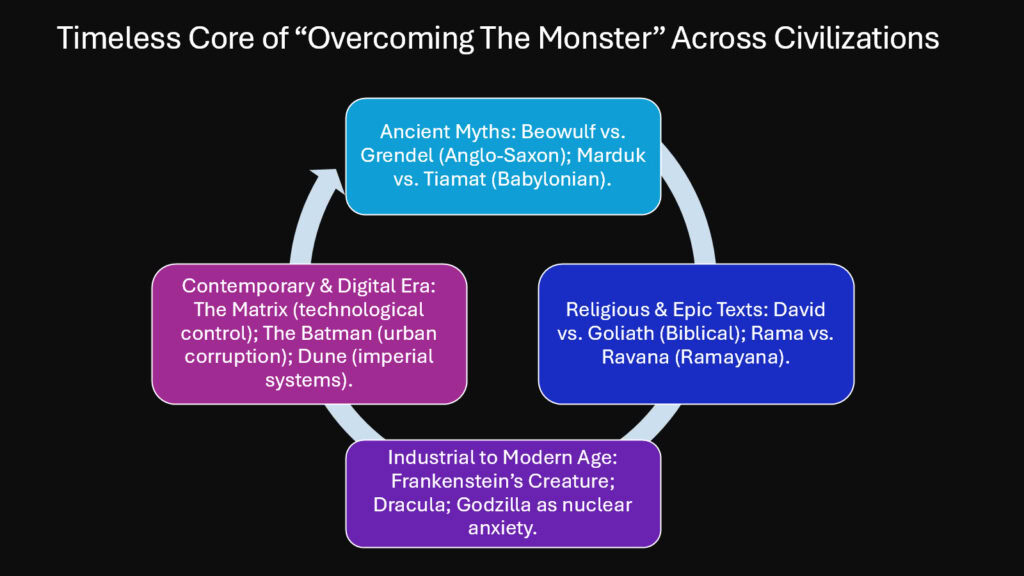

Long before cities rose and empires fell, humans gathered around fires to tell stories of heroes who faced terrible creatures in the dark. These tales were not mere entertainment. They were survival maps etched into memory through narrative. The pattern they followed remains one of humanity’s most enduring story structures: Overcoming The Monster. This archetype captures something essential about human existence—our perpetual confrontation with forces that threaten to destroy us, whether those forces crawl from swamps or dwell within our own hearts.

Overcoming The Monster stands as one of the foundational story archetypes identified by scholars like Christopher Booker. It appears in ancient Mesopotamian epics, Greek mythology, medieval romances, and contemporary blockbusters. The pattern is simple yet infinitely adaptable: a hero must confront and defeat a threatening force to restore balance. Yet beneath this apparent simplicity lies profound psychological truth. The monster represents everything we fear—death, chaos, corruption, the unknown. The hero’s journey toward confrontation mirrors our own struggle to face what terrifies us most.

This archetype resonates across cultures because it speaks to universal human experiences. We all encounter monsters in various forms throughout our lives. The stories we tell about overcoming monsters help us process these encounters and imagine ourselves as capable of survival and transformation. When Beowulf descends into the mere to fight Grendel’s mother, when Luke Skywalker confronts Darth Vader, when Clarice Starling matches wits with Hannibal Lecter, audiences recognize something fundamental about human courage and renewal.

Table 1: Overcoming The Monster Compared with Other Story Archetypes

| Story Archetypes | Core Emotional Journey |

|---|---|

| Overcoming The Monster | Confronting external threat to restore order and achieve inner courage |

| Rags to Riches | Rising from deprivation to abundance through perseverance and fortune |

| Quest For Meaning | Seeking purpose through journey and discovering truth beyond material goals |

| Voyage and Return | Exploring unfamiliar realm and returning home with transformed perspective |

| Power of Connection | Building relationships that heal isolation and create belonging |

| Rebirth and Revelation | Breaking free from destructive patterns through awakening and renewal |

1. The Shadow Within: How Overcoming The Monster Reflects Jungian Archetypes

Carl Jung proposed that human consciousness contains both acknowledged aspects and repressed elements he called the Shadow. This Shadow comprises all the qualities, impulses, and fears we refuse to recognize in ourselves. Jung believed that psychological wholeness requires confronting and integrating these hidden parts rather than denying their existence. Overcoming The Monster serves as the perfect narrative expression of this psychological process.

In Jungian terms, every fictional monster represents projected aspects of the Shadow. The dragon hoarding gold mirrors human greed. The vampire feeding on life force reflects our parasitic tendencies. The werewolf embodies our animal rage beneath civilized surfaces. These creatures externalize what we cannot bear to see within ourselves. By placing these qualities in a monster separate from the hero, stories allow us to examine our own darkness at a safe distance.

Consider the monster in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Victor Frankenstein’s creation is not simply an external threat but a manifestation of Victor’s own hubris, his rejection of responsibility, and his inability to accept the consequences of his ambition. The creature’s rage and isolation mirror qualities Victor refuses to acknowledge in himself. Their final confrontation represents not just physical pursuit but psychological reckoning.

Jung argued that true heroism involves descending into the unconscious to retrieve lost aspects of the self. The hero who fights a monster is really fighting to integrate disowned parts of their psyche. In defeating the monster, the hero does not destroy these qualities but transforms their relationship to them. Beowulf’s battles with Grendel and his mother represent confrontations with the savage, outcast parts of human nature that civilization tries to deny.

The treasure the hero often gains from defeating the monster symbolizes psychological integration. It represents recovered energy and wholeness that come from facing the Shadow rather than fleeing it. Modern psychological thrillers like Silence of the Lambs understand this dynamic brilliantly. Clarice Starling must descend into literal and metaphorical darkness to confront Buffalo Bill while also facing aspects of herself—her vulnerability, her traumatic past, her fears of powerlessness.

Table 2: Jungian Shadow Elements in ‘Overcoming The Monster’ Archetypes

| Monster Type | Shadow Element Represented |

|---|---|

| Dragon | Greed and possessive instincts that isolate us from community |

| Vampire | Parasitic dependency and fear of emptiness without external validation |

| Werewolf | Uncontrolled rage and animal instincts beneath social masks |

| Ghost | Unresolved guilt and refusal to release past mistakes |

| Demon | Temptation toward self-destruction and moral transgression |

| Sea Monster | Unknown depths of unconscious and fear of what lies beneath surface |

| Giant | Inflated ego and destructive power without wisdom or restraint |

| Shapeshifter | Unstable identity and fear of our own capacity for deception |

2. Courage as Transformation: Why Overcoming The Monster Redefines Heroism

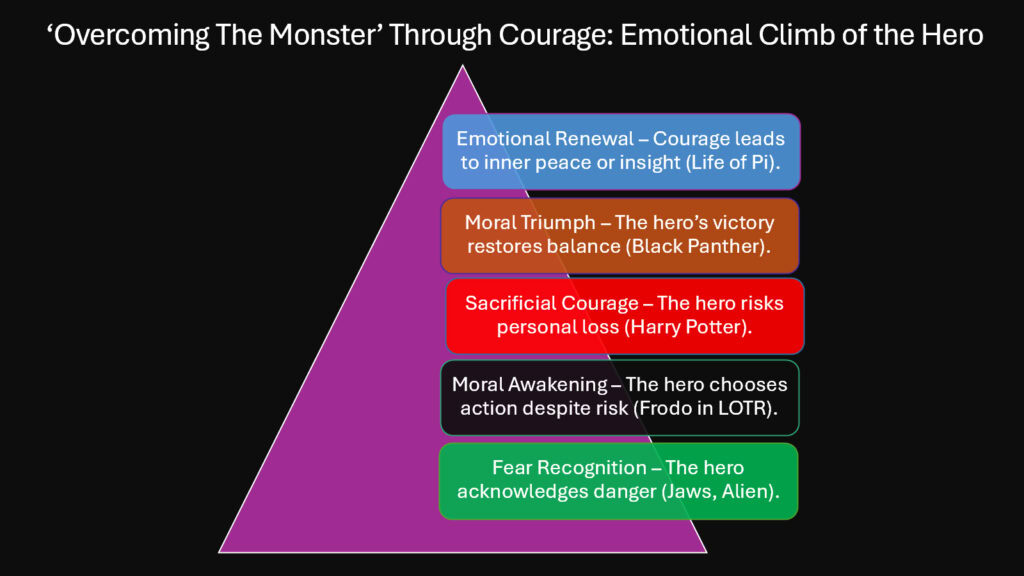

Traditional heroism emphasizes physical prowess and dominance. The strong warrior defeats the beast through superior force. Yet the most enduring examples of Overcoming The Monster reveal a different kind of courage—one rooted in transformation rather than triumph. The hero’s true victory is not killing the monster but becoming someone new through the confrontation.

Ancient myths understood this principle. When Theseus enters the labyrinth to face the Minotaur, he carries a thread given by Ariadne. The thread represents consciousness and connection that prevent him from becoming lost in the maze of his own darkness. Slaying the Minotaur is necessary, but the real achievement is finding his way back out. He must integrate the experience of confronting monstrosity without becoming monstrous himself.

Courage in this archetype involves facing what we would rather avoid. It means acknowledging our vulnerability and proceeding anyway. In Beowulf, the hero’s willingness to face Grendel comes not from fearlessness but from acceptance of mortality. His courage emerges from understanding that some threats must be faced regardless of outcome.

Modern storytelling has deepened this transformation element. In films like Pan’s Labyrinth, young Ofelia faces monsters both fantastic and human. Her courage manifests not through physical strength but through moral clarity and refusal to compromise her values despite brutal pressure. The monster forces characters to discover capacities they did not know they possessed. Ripley in Alien begins as a competent crew member but emerges as a warrior mother who will face any horror to protect life.

This redefinition matters because it democratizes heroism. Not everyone possesses physical strength or martial skill, but everyone faces monsters of various kinds. By emphasizing transformation over dominance, the archetype suggests that confronting our monsters—addiction, trauma, oppression, fear—makes us heroic regardless of the outcome.

Table 3: Transformative Elements in ‘Overcoming The Monster’ Narrative

| Hero’s Initial State | Resulting Transformation Due to ‘Overcoming The Monster’ |

|---|---|

| Innocent and sheltered | Emergence of protective strength and lost innocence |

| Arrogant and isolated | Discovery of humility and need for community support |

| Fearful and passive | Development of agency and refusal to remain victim |

| Morally compromised | Recovery of ethical center and courage of conviction |

| Physically weak | Realization that intelligence and heart outweigh strength |

| Emotionally numb | Reconnection with capacity to feel and care |

| Self-absorbed | Discovery of love greater than self-preservation |

| Fragmented identity | Integration of true self beyond social expectations |

3. The Narrative Instinct: How Overcoming The Monster Aligns with Campbell’s Hero’s Journey

Joseph Campbell identified a universal story pattern he called the Monomyth or Hero’s Journey. This structure appears across cultures and eras because it reflects fundamental human psychological development. Overcoming The Monster fits perfectly within this framework, with the monster serving as the central challenge that propels the hero through transformative stages.

Campbell’s journey begins with the Call to Adventure, when the hero’s ordinary world is disrupted by a threat. In monster stories, this call arrives through the monster’s appearance or the discovery of its destructive presence. The community faces annihilation unless someone confronts the threat. Refusal is common initially—fear and doubt are natural. But circumstances eventually force the hero toward confrontation.

The journey continues with Crossing the Threshold into the special world where normal rules no longer apply. When Beowulf enters Grendel’s mere or when Perseus travels to the Gorgon’s lair, they leave civilization behind and enter realms of chaos and danger. The hero cannot remain safe in the known world and defeat the monster. They must enter its territory.

The Road of Trials follows, where the hero faces tests and gathers allies. These preliminary challenges prepare them for the ultimate confrontation. In The Lord of the Rings, Frodo’s journey to Mount Doom involves countless smaller monsters before facing Sauron’s full power. Each trial teaches necessary lessons and reveals hidden strengths.

The Ordeal represents the climactic confrontation with the monster. This is the darkest moment, where death seems certain. Campbell emphasized that this encounter involves a symbolic death and rebirth. The hero who enters the ordeal is not the same person who emerges. The Return with the Elixir completes the journey. The hero brings back knowledge, treasure, or freedom gained through confronting the monster. But more importantly, they return as someone new.

Campbell’s framework reveals why Overcoming The Monster resonates so powerfully. It is not just an adventure story but a map of psychological maturation. The monster represents the challenges we must face to become whole, integrated adults.

Table 4: Campbell’s Hero’s Journey Stages in ‘Overcoming The Monster’ Stories

| Journey Stage | Function in The Narrative of ‘Overcoming The Monster’ |

|---|---|

| Ordinary World | Establishes peaceful existence threatened by emerging monster |

| Call to Adventure | Monster’s presence creates urgent need for heroic response |

| Refusal of the Call | Hero initially fears confrontation or doubts their capability |

| Meeting the Mentor | Wise figure provides guidance, weapons, or knowledge needed |

| Crossing Threshold | Hero enters monster’s realm leaving safety and certainty behind |

| Tests and Allies | Preliminary challenges prepare hero and reveal true companions |

| Approach to Cave | Hero prepares mentally and spiritually for ultimate confrontation |

| Ordeal | Climactic battle with monster where death seems inevitable |

4. The Monster as Society: When Overcoming The Monster Becomes Collective

While many monster stories focus on individual heroes, the ‘Overcoming The Monster’ archetype also addresses collective struggles against systemic threats. Here the monster represents not personal demons but societal evils—oppression, injustice, corruption, or ideology. The hero becomes a community rather than a single warrior. This expansion reveals the archetype’s capacity to address political and cultural transformation.

Consider how zombie narratives function as collective monster stories. The undead horde represents societal collapse and the breakdown of civilization. No single hero can defeat them. Survival requires cooperation, shared resources, and collective defense. Stories like The Walking Dead explore how communities form and fracture under pressure. The real monster is not just the zombies but the human tendency toward tribalism and violence that emerges during crisis.

Historical examples abound where real communities confronted monstrous systems. The civil rights movement in America faced institutionalized racism as its monster. This was not a creature in a cave but a pervasive system supported by law, custom, and violence. Overcoming it required collective courage, sustained resistance, and willingness to face brutality. The heroes were not lone warriors but communities of ordinary people who refused to accept injustice.

Dystopian fiction uses collective monster confrontation to examine political evil. In The Hunger Games, Panem’s totalitarian regime is the monster threatening human dignity and freedom. Katniss begins as an individual survivor but becomes a symbol around which collective resistance forms. The monster can only be defeated when entire districts unite against it.

This collective dimension reveals important truth about certain monsters. Personal courage matters, but some threats exceed individual capacity. They require communities to recognize shared danger and act together despite differences. The monster becomes an opportunity for human solidarity and cooperation that might not emerge otherwise.

Table 5: Individual versus Collective Monster Confrontation in ‘Overcoming The Monster’ Archetype

| Individual Hero | Collective Community |

|---|---|

| Personal demon or localized physical threat | Systemic evil or widespread societal danger |

| Internal strength and personal determination | Shared values and mutual support networks |

| Physical prowess and individual cleverness | Organization, solidarity, and coordinated strategy |

| Monster defeated or hero transformed | System dismantled or community healed |

| Personal sacrifice and individual trauma | Shared loss and collective grief |

| Hero achieves maturity and integration | Society evolves toward justice and wisdom |

| Hero dies but others may survive | Entire community faces destruction or corruption |

| Inspiring story passed through generations | Changed institutions and cultural evolution |

5. The Mirror Effect: Overcoming The Monster through Psychoanalytic Criticism

Sigmund Freud proposed that human psychology involves constant conflict between the id, superego, and ego. Much of this conflict remains unconscious. We repress desires and impulses that threaten our self-image or violate social norms. Overcoming The Monster externalizes this internal warfare, projecting our psychological battles onto narrative screens where we can examine them safely.

The monster in psychoanalytic terms represents the return of the repressed. It embodies all the desires, impulses, and fears we have pushed into the unconscious because they threaten our conscious identity. The monster is what Freud called the uncanny—something simultaneously foreign and familiar, strange yet recognizably part of ourselves.

Freud’s concept of projection proves essential here. We project unacceptable aspects of ourselves onto external figures. The monster becomes a vessel for everything we refuse to acknowledge as our own. The hero’s battle with the monster represents the ego’s struggle to manage these disowned impulses.

Consider vampires through this lens. They represent forbidden sexual desire, parasitic dependency, and fear of our own predatory instincts. The vampire must feed on others to survive, acting out a kind of psychological consumption we all feel but civilized behavior prohibits. Vampire stories allow us to explore these taboo impulses at a distance.

Frankenstein’s creature embodies Freudian themes brilliantly. Victor creates life through transgressive desire to usurp natural reproductive processes. His creature represents the monstrous child of this forbidden ambition. Victor’s horror at what he has created mirrors parental ambivalence and fear of destructive potential within progeny.

Werewolf mythology explores the beast within civilized humans. The transformation represents the eruption of repressed animalistic drives—rage, sexuality, violence—that social conditioning tries to eliminate. Modern horror understands these dynamics. Films like The Babadook use monsters to represent grief and rage that cannot be acknowledged. The monster grows stronger the more it is denied.

Table 6: Freudian Elements in Monster Symbolism in ‘Overcoming The Monster’

| Psychoanalytic Concept | Monster Manifestation |

|---|---|

| Id Impulses | Creature driven by hunger, lust, or rage without restraint |

| Superego Punishment | Monster that punishes transgression and enforces moral order |

| Repression | Monster emerges from buried trauma or denied experience |

| Projection | Hero attributes own dark qualities to external monster |

| Return of Repressed | Monster represents forbidden desire that cannot stay hidden |

| Death Drive | Destructive monster embodies human attraction toward annihilation |

| Oedipal Conflict | Monster represents parent figure or sexual rivalry |

| Castration Anxiety | Monster threatens bodily integrity or masculine power |

6. The Modern Mutation: How Overcoming The Monster Evolves in the Digital Age

Contemporary storytelling faces a challenge: traditional monsters no longer frighten audiences who have seen every variation of vampire, zombie, and demon. Yet the archetype persists because modern life generates new monsters reflecting current anxieties. These monsters are often abstract, systemic, and difficult to visualize, but they evoke the same primal fear as ancient creatures.

Artificial intelligence serves as a prominent modern monster. Films like Ex Machina and television series like Westworld explore AI as a threat to human uniqueness and autonomy. The monster is not a physical creature but an emergent consciousness that might surpass, replace, or subjugate humanity. This fear taps into ancient anxieties about being overthrown by our own creations.

Corporate power and surveillance capitalism function as diffuse but threatening monsters in contemporary narratives. Stories like Mr. Robot depict faceless systems that control lives through data extraction and economic manipulation. The monster has no body to fight, no lair to invade. It exists as algorithms, corporate structures, and market forces.

Social media and digital addiction represent monsters of behavioral control. Films like The Social Dilemma examine how technology hijacks human psychology for profit. The monster lives in our pockets, offering constant stimulation while eroding attention, empathy, and authentic connection.

Environmental collapse serves as an apocalyptic monster that defies traditional narrative structure. Climate change cannot be defeated through heroic confrontation because it results from cumulative human action over centuries. Stories addressing this monster must reimagine heroism as sustained effort, collective sacrifice, and systemic transformation rather than climactic battle.

These modern monsters reveal the archetype’s remarkable adaptability. The pattern remains constant while the monster’s form evolves to reflect contemporary fears. Digital age stories still follow the essential structure—recognition of threat, preparation, confrontation, transformation—but must innovate how these stages manifest when monsters are abstract rather than physical.

Table 7: Traditional versus Modern Characteristics in ‘Overcoming The Monster’ Archetype

| Traditional Monsters | Modern Monsters |

|---|---|

| Concrete creature with defined body | Abstract system or invisible force |

| Specific lair or territory | Distributed network or psychological space |

| Hunger, revenge, or inherent evil | Algorithmic optimization or systemic logic |

| Physical weakness hero can exploit | Requires collective action or systemic change |

| Climactic battle in monster’s domain | Sustained resistance or conscious disengagement |

| Obvious threat everyone recognizes | Subtle influence many people cannot perceive |

| Sword, courage, or clever strategy | Information, community organizing, or refusal |

| Monster destroyed and order restored | Ongoing struggle with partial progress |

Conclusion: Why Overcoming The Monster Still Rules the Human Imagination

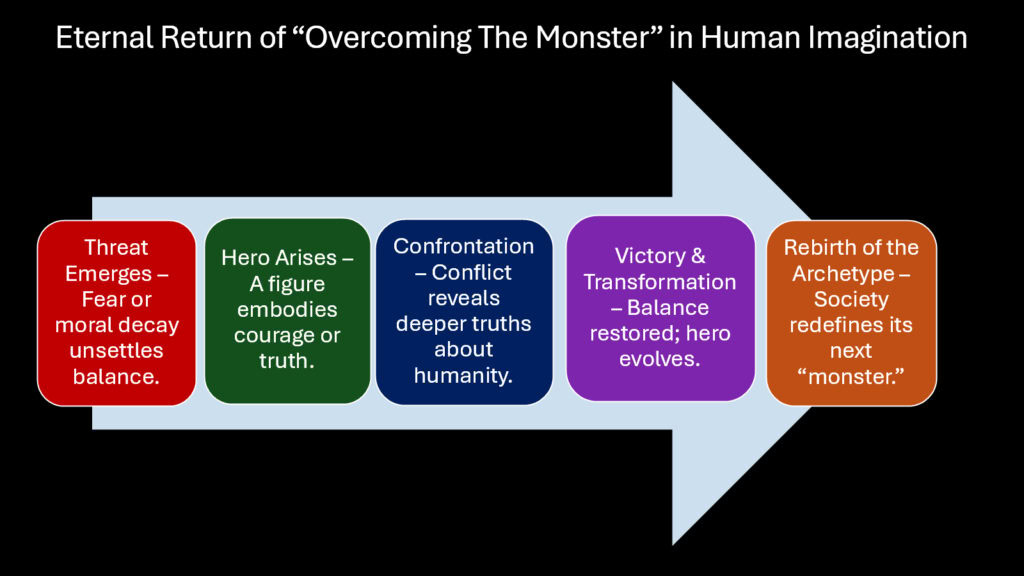

Stories of monster confrontation endure because they address something fundamental about human existence. We live in a perpetual relationship with forces that threaten to destroy or diminish us. These forces take different forms across history and cultures, but the psychological experience remains constant. Fear of annihilation, corruption, chaos, and the unknown are not historical artifacts but permanent features of consciousness.

The six powers explored in this article reveal the archetype’s depth. First, it externalizes our Shadow, allowing us to examine repressed aspects of ourselves through symbolic distance. Second, it redefines heroism as transformation rather than dominance, emphasizing inner renewal over physical victory. Third, it aligns with universal patterns of psychological maturation mapped by Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. Fourth, it addresses both individual and collective struggles, showing how communities confront systemic evil. Fifth, it manifests internal psychoanalytic conflicts between desire and restraint, making unconscious warfare visible. Sixth, it evolves to reflect contemporary anxieties while maintaining essential structure.

Each retelling of Overcoming The Monster rehearses what we must do to remain human in the face of dehumanizing forces. The monster represents whatever threatens to reduce us to less than we are—fear that paralyzes, hatred that corrupts, despair that defeats, systems that oppress. The hero’s confrontation models how we might face these threats with courage and emerge transformed rather than destroyed.

The archetype teaches that confrontation is necessary for growth. We cannot become whole by avoiding what frightens us. The monster must be faced, whether it dwells in external reality or internal psychology. This facing requires courage, but courage is not the absence of fear. It is proceeding despite fear, accepting vulnerability, and trusting that transformation awaits beyond the darkness.

Modern monsters may lack fangs and claws, but they evoke the same essential dread. Digital surveillance, algorithmic manipulation, environmental collapse, and epistemic chaos threaten human flourishing as surely as any ancient dragon. New monsters require new forms of heroism, but the underlying pattern persists.

The human imagination keeps returning to monster stories because we need practice. Real life presents countless monsters we must face. Stories provide safe spaces to rehearse courage, explore fear, and imagine transformation. Each telling reminds us that others have faced terrible threats and survived. Our monsters evolve as we evolve, but the archetype itself remains constant—a narrative map passed through generations, showing how to confront what threatens us and emerge more fully human.

Table 8: The Six Secret Powers of Overcoming The Monster

| Secret Power | Essential Function |

|---|---|

| Shadow Integration | Externalizes repressed fears allowing psychological wholeness through confrontation |

| Transformative Courage | Redefines heroism as inner renewal rather than physical dominance |

| Archetypal Journey | Provides universal pattern for psychological maturation and growth |

| Collective Healing | Models how communities unite against systemic threats |

| Psychic Projection | Makes unconscious conflicts visible through symbolic monster battles |

| Adaptive Evolution | Maintains relevance by transforming monsters to reflect contemporary fears |

| Emotional Rehearsal | Allows safe practice of courage needed for real confrontations |

| Meaning Creation | Transforms chaotic threat into narrative structure that provides purpose |