Table of Contents

Introduction: Plum Sugar Accumulation as a Biological Timing Problem

Credit: iken3

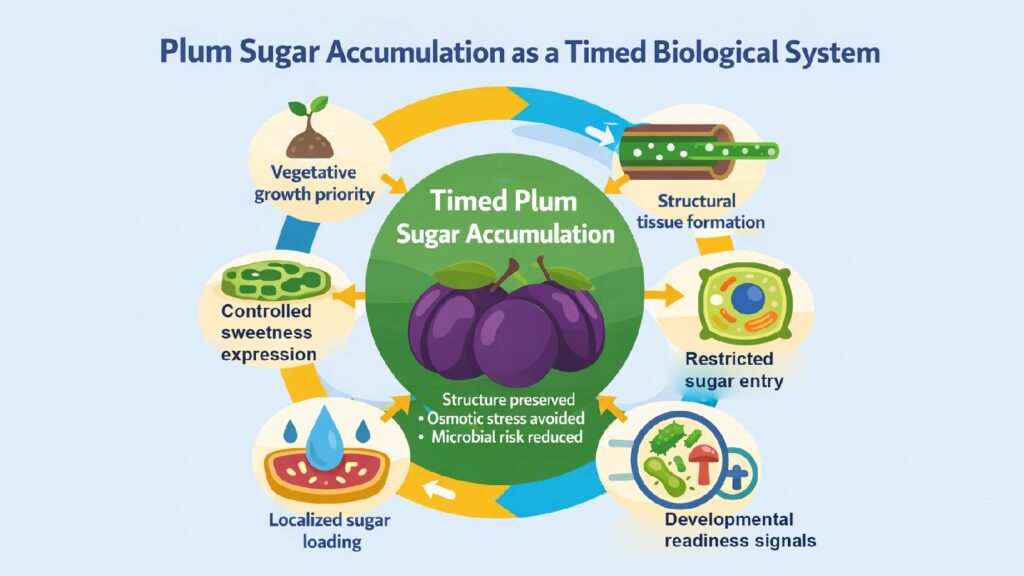

Plum sugar accumulation stands as one of nature’s clearest examples of controlled biological timing. Unlike a vessel filling slowly with liquid, sweetness does not arrive gradually in plum flesh. It appears late, concentrated in specific zones, and only when the fruit can structurally tolerate what sugar brings with it. The process is not about maximizing sweetness but about timing its arrival to avoid catastrophic failures in tissue stability, osmotic balance, and pathogen defense.

Sugars serve purposes beyond merely enhancing flavor. They draw in water, disrupt cell walls, and signal availability to microorganisms. An early buildup of sugars could jeopardize the integrity of fruit during cell division, create internal pressures that lead to the cracking of developing tissues, and invite infections before the maturation of seeds. Plums address this coordination challenge by utilizing molecular gates, creating tissue-level compartments, and employing synchronized softening processes that avert premature sweetness while guaranteeing optimal sugar distribution at the onset of ripening.

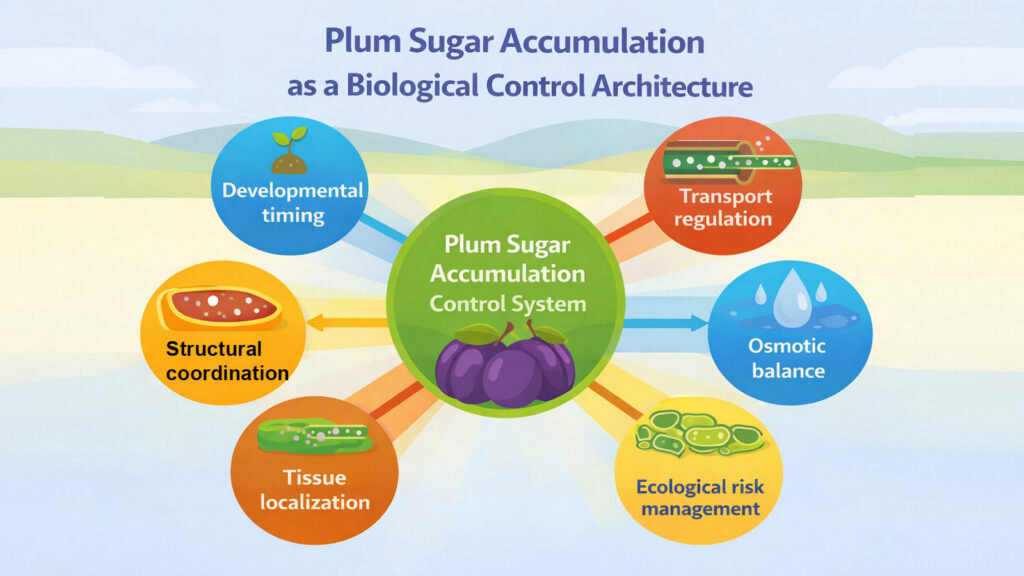

The delayed appearance of sugar in plums reflects deeper biological constraints. Growth requires firm tissue. Water balance demands careful osmotic control. Pathogen resistance depends on withholding nutrients until dispersal readiness. Each mechanism operates under opposing pressures, balancing energy allocation against structural integrity. Understanding plum sugar accumulation requires examining how these six interconnected systems manage a resource that simultaneously fuels ripening and threatens the fruit’s survival before seeds complete development.

Comparative Sugar Dynamics: Plum Sugar Accumulation Versus Other Rosaceae Fruits

| Rosaceae Fruits | Sugar Accumulation and Ripening Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Plums | Late Stage III concentrated burst with tightly synchronized softening; sucrose transport dominant; rapid accumulation in final two weeks before harvest |

| Apples | Extended gradual accumulation through Stage II-III with partial softening independence; sucrose and sorbitol transport; steady increase over months |

| Pears | Dual-phase accumulation on-tree and post-harvest with delayed softening; sorbitol conversion important; storage continuation after picking |

| Peaches | Rapid Stage III exponential increase nearly simultaneous with softening; sucrose transport; compressed final growth phase with dramatic sweetening |

| Cherries | Sharp spike during compressed final growth phase preceding softening slightly; sucrose dominant; very brief accumulation window before harvest |

| Apricots | Moderate Stage III accumulation coordinated with color change; sucrose with moderate sorbitol; intermediate rate between plums and apples |

| Raspberries | Distributed accumulation across ripening stages with minimal softening; sucrose transport; progressive increase during receptacle expansion |

| Strawberries | Progressive accumulation through color stages independent of firmness; sucrose converts to hexoses; white to red transition marks sugar increase |

1. Plum Sugar Accumulation Begins With Controlled Phloem Sugar Delivery

Phloem transport determines when and how sugars reach developing plums. Unlike photosynthesis occurring within the fruit itself, plum sugar accumulation depends entirely on carbohydrate delivery from leaves through vascular conduits. This dependence creates a regulatory bottleneck that prevents early flooding of immature tissue with osmotically active compounds.

During early plum development, phloem unloading proceeds through symplastic pathways where sugars move cell-to-cell through plasmodesmata connections. This route limits delivery speed and maintains lower sugar concentrations in young fruit. As plums enter rapid expansion phases, the unloading mechanism shifts toward apoplastic pathways requiring active transport across cell membranes. This transition allows higher sugar flux but remains under tight regulatory control through transporter protein expression.

Source-sink relationships govern how much sugar leaves allocate to developing plums. Young fruits compete with vegetative growth and other sinks for available photoassimilates. Research on plum cultivars shows that sink strength increases dramatically during stage three growth when fruits undergo their final exponential expansion. Enhanced sink strength correlates with upregulation of SWEET family genes that facilitate sugar efflux from phloem into fruit parenchyma.

Transport capacity changes through development reflect modifications in vascular architecture and transporter abundance. Early-stage plums possess limited phloem connections and lower membrane transporter expression. As fruit matures, vascular surface area increases and sucrose synthase activity rises to convert incoming sucrose into storage forms. The delay between transport capacity development and actual sugar loading creates a temporal buffer that protects structural integrity during critical growth phases.

Phloem Transport Control During Plum Sugar Accumulation

| Developmental Phase | Transport Characteristics and Regulation |

|---|---|

| Cell Division (Stage I) | Symplastic unloading with limited flux; minimal delivery maintained through low SWEET expression and plasmodesmata gating |

| Pit Hardening (Stage II) | Reduced transport during growth pause; near-zero accumulation as endocarp development takes priority with active suppression |

| Early Expansion (Stage III-A) | Transitioning to apoplastic pathways; gradual capacity building through increasing transporter gene expression |

| Pre-Ripening (Stage III-B) | Predominantly apoplastic unloading; accelerating but controlled flow via SWEET upregulation and sink strength signaling |

| Active Ripening (Stage IV-I) | Fully apoplastic with maximum sustained delivery; peak PsSWEET1/9 expression coupled with high sucrose synthase activity |

| Late Ripening (Stage IV-II) | Declining transport efficiency as maturation completes; reduced delivery due to phloem breakdown and membrane integrity loss |

2. Plum Sugar Accumulation Is Delayed by Developmental Stage Signaling

Credit: iken3

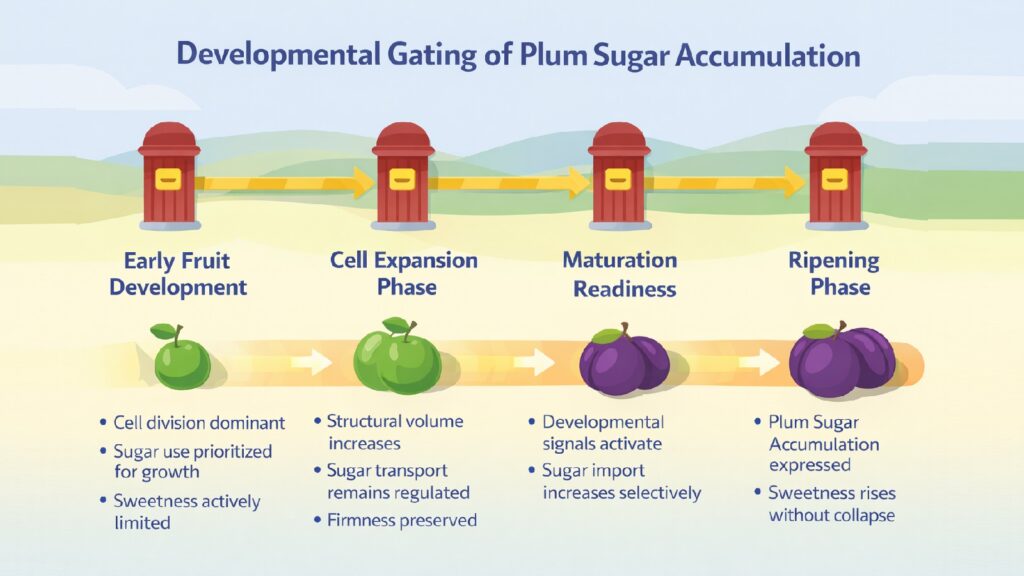

Developmental signals actively prevent sugar loading in immature plums. This is not passive resistance but coordinated suppression of the molecular machinery required for sugar uptake and storage. Immature fruits prioritize cell division, structural development, and seed maturation over sugar accumulation.

Fruit growth phases dictate when sugar accumulation becomes permissible. During cell division phases, plums undergo a rapid increase in cell number while maintaining relatively low soluble sugar levels. This phase requires that cells remain small and division-competent rather than expanding through water uptake driven by osmotic gradients. Regulatory proteins suppress sugar transporter genes and maintain low vacuolar sugar concentrations.

Cell expansion phases introduce different regulatory considerations. As cells stop dividing and begin enlarging, the fruit enters a phase where water uptake becomes the primary growth driver. During this transition, plums maintain a firm texture through high organic acid content and limited sugar presence. The firmness protects against mechanical damage and allows continued photosynthetic activity in fruit tissue.

The transition to maturation involves hormonal signals that lift suppression of sugar-related genes. Ethylene, auxin, and abscisic acid coordinate ripening initiation in different plum varieties. In climacteric plums, rising ethylene levels trigger expression of genes encoding sugar transporters, vacuolar invertases, and sucrose synthases. Research on Prunus salicina transcription factors identified PsbHLH58 as directly regulating PsSUS4, a key sucrose synthase gene whose expression correlates strongly with sugar accumulation timing.

Developmental Checkpoints Regulating Plum Sugar Accumulation

| Growth Stage | Sugar Status and Regulatory Control |

|---|---|

| Early Cell Division | Minimal accumulation (2-4% soluble solids) maintained through active transporter suppression with growth-promoting hormones dominant |

| Late Cell Division | Restricted levels (4-6% soluble solids) with continued suppression as cells complete final divisions and begin fate determination |

| Cell Expansion | Gradually permitted increase (6-8% solids) through partial transporter activation balanced by acid accumulation controlling osmotic pressure |

| Pre-Climacteric | Accelerating accumulation (8-12% solids) as ripening hormone synthesis begins and transcription factor activation initiates |

| Climacteric | Rapid accumulation phase (12-18% solids) with full transporter expression and enzyme activation enabling conversion and storage |

| Post-Climacteric | Plateau or slight decline as tissue breakdown begins; transport system deterioration and senescence processes initiate |

3. Plum Sugar Accumulation Is Localized to Specific Tissues

Sugar distribution within plums is notably uneven. Rather than uniform sweetness throughout the flesh, sugars concentrate in zones related to vascular proximity and tissue function. This spatial organization reflects how plums manage competing demands for energy storage, structural maintenance, and controlled texture change.

The mesocarp, constituting bulk fruit flesh, shows internal gradients in sugar concentration. Tissues closest to vascular bundles accumulate sugars first, creating concentration gradients that drive diffusion into peripheral cells. Research using tissue sampling at different depths within plum flesh reveals that areas within several cell layers of phloem terminals contain notably higher sugar levels than surface regions.

Exocarp tissue demonstrates distinct sugar accumulation patterns compared with internal flesh. The skin and several cell layers beneath maintain lower sugar concentrations throughout most of development. This pattern serves multiple functions related to pathogen defense and structural integrity. Lower sugar content in surface tissues reduces microbial attraction and maintains a firmer protective barrier longer into the ripening process.

Proximity to vascular tissue determines localized accumulation timing and intensity. Cells surrounding phloem sieve elements experience the highest sugar exposure and develop specialized storage capacity. These cells possess larger vacuoles and higher expression of sugar transporters that facilitate vacuolar sequestration.

Tissue-Specific Patterns of Plum Sugar Accumulation

| Tissue Zone | Sugar Distribution and Timing Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Vascular-adjacent mesocarp | Highest concentration (reference 100%) with earliest accumulation peak; primary storage site driving osmotic water movement |

| Deep mesocarp | Moderate to high levels (75-85%) accumulating mid-ripening; bulk storage region undergoing active texture modification |

| Peripheral mesocarp | Moderate concentration (60-75%) with later ripening peak; secondary storage maintaining gradient toward surface |

| Exocarp inner layers | Lower accumulation (40-60%) delayed from internal peak; maintains structural support and contributes to pathogen resistance |

| Exocarp surface | Lowest sugar levels (30-50%) with latest or incomplete accumulation; preserves protection and surface integrity longest |

| Endocarp surrounding tissue | Variable levels (20-80% stage-dependent) with minimal accumulation; provides structural separation and seed protection |

4. Plum Sugar Accumulation Is Balanced Against Osmotic Pressure

Credit: iken3

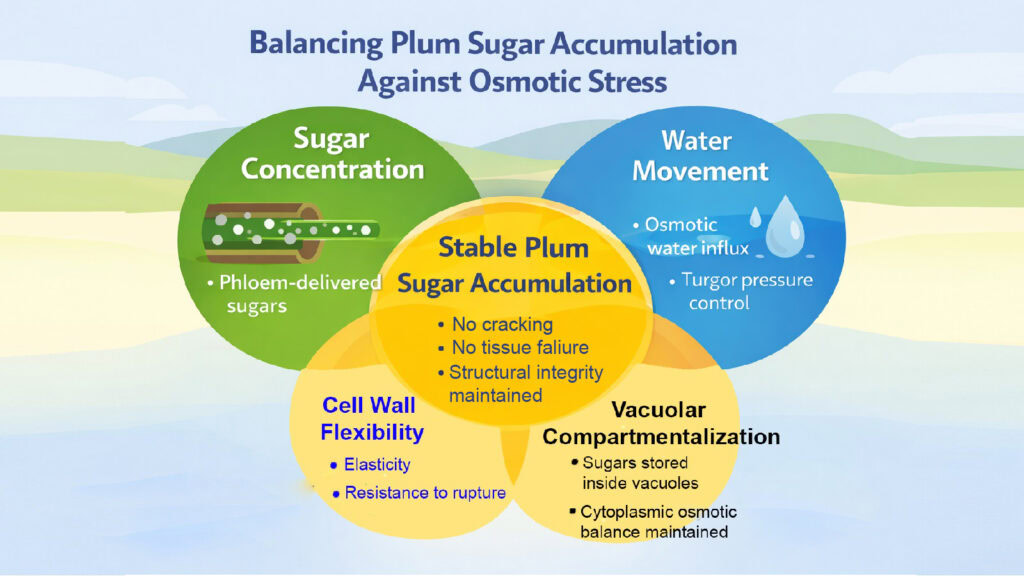

Managing osmotic pressure represents a fundamental challenge during plum sugar accumulation. Every molecule of sugar dissolved in cellular fluid reduces water potential and creates a force driving water influx. Uncontrolled accumulation would draw excessive water, swell cells beyond capacity, and rupture tissues before ripening is complete.

Water potential components govern fluid movement into and within fruit tissues. The water potential equation includes osmotic potential, pressure potential, and matric potential. Research measuring these parameters in developing plums shows osmotic potential decreasing as sugar accumulates, pulling water potential lower and creating a gradient that draws water from the xylem.

Turgor pressure changes dramatically during plum development in response to sugar accumulation. Young fruits maintain high turgor, supporting cell expansion and tissue rigidity. As sugar loading begins, turgor initially remains elevated but then declines during ripening despite increasing osmotic potential. This seemingly paradoxical drop occurs because water movement lags behind sugar accumulation, and cell wall loosening reduces pressure containment.

Cracking susceptibility relates directly to osmotic imbalances created during rapid sugar accumulation. When sugar influx exceedsthe rate at which water transport and cell wall adjustment can accommodate osmotic changes, internal pressure exceeds skin tensile strength. Certain plum cultivars show high cracking incidence correlated with rapid late-season sugar accumulation patterns.

Cell wall flexibility must increase in coordination with sugar accumulation to prevent structural failure. The walls contain pectin networks that can be modified through enzymatic activity to increase extensibility. As sugar begins accumulating, pectin methylesterase and polygalacturonase expression rise, initiating controlled wall loosening.

Osmotic Management During Plum Sugar Accumulation

| Parameter | Developmental Changes and Functional Impact |

|---|---|

| Osmotic Potential | Declines from -0.8 to -1.2 MPa early to -2.2 to -2.8 MPa at peak accumulation; drives water uptake and creates turgor |

| Turgor Pressure | Decreases from 0.4-0.6 MPa during development to 0.05-0.15 MPa in ripe fruit; indicates structural relaxation and wall modification |

| Water Potential | Progresses from -0.4 to -0.8 MPa early through -2.0 to -2.7 MPa late ripening; determines direction and rate of water movement |

| Cell Wall Extensibility | Increases from low (firm tissue) through moderate to high (soft tissue); allows osmotic expansion without catastrophic failure |

| Soluble Solids Content | Rises from 4-6% in young fruit through 8-12% pre-ripening to 14-20% at maturity; direct measure of sugar accumulation progress |

| Cracking Risk | Minimal early, moderate during transition, highest at peak accumulation; reflects balance between osmotic stress and structural capacity |

5. Plum Sugar Accumulation Is Coordinated With Cell Wall Modification

Cell wall disassembly proceeds in concert with sugar accumulation rather than preceding it. This coordination ensures that sweetness appears only when softening mechanisms can manage the osmotic and structural consequences. The cell wall serves as both a physical barrier and a tension-bearing structure.

Pectins undergo extensive modification during the period of active sugar accumulation. These complex polysaccharides form much of the middle lamella, binding cells together. Pectin methylesterase removes methyl groups from homogalacturonan chains, making them susceptible to degradation by polygalacturonase. Research on stone fruit ripening shows pectin methylesterase activity increases several days before major sugar accumulation begins.

Hemicellulose networks experience targeted breakdown, supporting controlled softening synchronized with sweetening. Xyloglucan, a major hemicellulose component, interacts with cellulose microfibrils to maintain wall strength. Enzymes, including xyloglucan endotransglycosylase and expansin proteins, modify these networks during ripening.

Timing precision in enzyme activation prevents textural disasters. If wall-degrading enzymesare activated before sugar accumulation, fruits would soften prematurely and become vulnerable to damage without achieving sweetness. Transcriptional regulation coordinates these processes through shared control by ripening master regulators.

Enzyme Activity Coordination With Plum Sugar Accumulation

| Cell Wall Enzyme Type | Activity Timing and Softening Impact |

|---|---|

| Pectin Methylesterase (PME) | Precedes rapid sugar phase by 3-7 days; prepares methylated homogalacturonan for degradation with minimal initial softening |

| Polygalacturonase (PG) | Coincident with rapid sugar accumulation; degrades demethylated pectin causing major softening and middle lamella dissolution |

| Pectate Lyase (PL) | Slightly lags sugar accumulation peak; cleaves calcium-bound pectin producing significant softening and cell separation |

| Beta-Galactosidase | Overlaps sugar accumulation period; removes galactan side chains contributing moderate softening effect |

| Expansin Proteins | Precedes sugar peak by 1-3 days; disrupts non-covalent polymer interactions enabling wall extension and facilitating softening |

| Xyloglucan Endotransglycosylase | Active throughout ripening period; remodels xyloglucan chains maintaining controlled progressive wall modification |

6. Plum Sugar Accumulation Reduces Microbial Vulnerability Through Timing

Delaying sugar accumulation serves critical defense functions against microbial pathogens. Sugar represents a premium nutrient attracting fungi and bacteria. Early presence would advertise fruit availability before seeds mature and dispersal mechanisms activate. By withholding sweetness until late development, plums maintain a lower infection risk during vulnerable growth phases.

Immature fruits possess active defense systems, including chemical deterrents and wound healing capacity. Young plums contain elevated levels of organic acid, creating a low pH hostile to many pathogens. They also express genes encoding pathogenesis-related proteins and antimicrobial peptides. Research on stone fruit pathogen resistance documents that infection success rates in green fruit remain low even when pathogens gain entry.

Quiescent infections demonstrate how pathogens exploit ripening-associated sugar increases. Many fungal species, including Botrytis, Monilinia, and Colletotrichum, can establish symptomless infections in developing fruit, remaining dormant until ripening begins. Studies using molecular detection methods found these pathogens present in high percentages of symptom-free green plums.

The ripening transition increases susceptibility through multiple mechanisms beyond simple sugar availability. Cell wall softening provides easier penetration routes. Defense compound levels decline. Ethylene, which promotes ripening and sugar accumulation, can also suppress certain immune responses.

Seed maturity determines optimal timing for accepting increased infection risk. From an evolutionary perspective, fruit vulnerability becomes acceptable once seeds achieve dispersal capability. Early infections compromise seed development and reduce reproductive success.

Pathogen Defense Changes During Plum Sugar Accumulation

| Defense Parameter | Defense Status Across Development |

|---|---|

| Sugar Availability | Minimal in immature fruit (poor nutrient source) progressing to maximum in late ripening (optimal pathogen substrate) |

| Surface pH | Strongly acidic (pH 3-3.5) in young fruit moderating through ripening to neutral-slightly acidic (pH 4.2-4.8) at maturity |

| Antimicrobial Compounds | High concentration maintained early declining rapidly during ripening transition to very low or absent in ripe fruit |

| Cell Wall Integrity | Intact barrier structure in development weakening during transition to compromised easily-penetrated state in ripe fruit |

| Active Immune Response | Strong inducible defenses early becoming downregulated during ripening with minimal residual activity in mature fruit |

| Quiescent Pathogen Status | Dormant with limited growth in green fruit; activation triggered during ripening; active growth and sporulation in ripe fruit |

Conclusion: What Plum Sugar Accumulation Reveals About Biological Control Systems

Credit: iken3

Plum sugar accumulation demonstrates how living organisms solve coordination problems requiring multiple independent processes to converge within narrow temporal windows. The challenge extends beyond simply producing and transporting sugar. Success requires preventing premature accumulation that would destabilize structure, managing osmotic consequences that could rupture tissues, synchronizing softening with sweetness, and timing vulnerability increases to coincide with seed maturity.

Each of these Plum Sugar Accumulation mechanisms operates under constraints from others. Phloem delivery rates must remain limited during growth to prevent osmotic disruption. Developmental signals must suppress accumulation despite transport capacity to preserve firmness. Tissue localization must create gradients supporting both storage and structural integrity. Osmotic management requires cell wall flexibility, arriving precisely when sugar loading accelerates.

The system reveals evolutionary optimization toward temporal precision rather than maximum output. Plums could potentially accumulate sugar earlier and achieve higher concentrations if timing constraints were lifted. However, doing so would sacrifice structural integrity during growth, increase cracking susceptibility, trigger premature softening, and expose developing seeds to pathogen damage.

Biological control systems managing delayed rewards face similar architecture challenges across contexts. Whether examining seed maturation, metamorphosis completion, or immune system development, organisms must coordinate multiple rate-limiting processes while preventing premature activation of terminal programs. The principles visible in plum sugar accumulation, including molecular gatekeeping, tissue-level compartmentalization, osmotic engineering, and strategic vulnerability acceptance, appear repeatedly in developmental biology.

Plum sugar accumulation ultimately demonstrates that biological sophistication often manifests not in complexity of individual mechanisms but in precision of their coordination. The fruit neither maximizes sweetness nor delays ripening indefinitely. Instead, it identifies optimal timing given structural constraints, physical requirements, and ecological pressures.

Systems-Level Integration of Plum Sugar Accumulation Control Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Control Integration and Failure Consequences |

|---|---|

| Phloem Transport Control | Delivery rate coordinates with developmental signals and osmotic limits; timing failure causes structural damage from premature loading |

| Developmental Gating | Stage-specific expression links to enzyme activation and transport capacity; mistiming produces firmness loss without sweetness |

| Tissue Localization | Spatial gradients support osmotic management and softening zones; failure causes uniform structural collapse |

| Osmotic Management | Water potential balance requires synchronized wall modification; poor coordination results in fruit cracking or cell rupture |

| Cell Wall Coordination | Enzyme timing permits osmotic expansion and sugar storage; mistiming causes premature tissue rot or rigid tissue damage |

| Defense Timing Strategy | Seed maturity alignment balances all mechanisms against pathogen risk; early failure results in seed loss from infection |