Table of Contents

Introduction: Power and Corruption – Why Good Intentions Create the Most Dangerous Stories

Power and Corruption stands among the oldest and most vital themes in storytelling. It appears in myths, novels, plays, and films because it reflects something deeply human. The pattern repeats across cultures and centuries. A character begins with noble dreams, fights for justice, or tries to protect others. Then something shifts. The same person who once inspired trust becomes the source of fear. What makes this theme so powerful is not the presence of evil from the start but the transformation of good into something unrecognizable.

Stories about Power and Corruption work because they show us how fragile moral certainty can be. A hero’s purity often becomes the very thing that blinds them. When someone believes they are acting for the right reasons, they stop questioning their methods. They lose the ability to see how their actions harm others. Literature uses this slow decay to create tension. Readers watch characters slide into cruelty while still believing they are righteous. This makes the fall both tragic and terrifying.

These narratives resonate because we recognize pieces of ourselves in them. Most people do not see themselves as villains. We justify our choices, tell ourselves we had no other option, or believe our intentions outweigh the damage we cause. Stories about corrupted goodness hold up a mirror. They remind us that the distance between protector and oppressor is shorter than we think. This universal recognition is what keeps the theme alive across generations.

Power and Corruption Compared to Other Major Storytelling Themes

| Theme | Core Focus |

|---|---|

| Power and Corruption | Transformation of virtue into tyranny through authority |

| Love and Loss | Emotional bonds and the pain of separation or absence |

| Survival | Physical and psychological endurance against hostile forces |

| Good vs. Evil | Clear moral opposition between opposing forces |

| Destiny vs. Choice | Tension between predetermined fate and free will |

| Redemption and Forgiveness | Healing past wrongs through change and acceptance |

1. Power and Corruption: When Virtue Becomes a Hidden Weakness

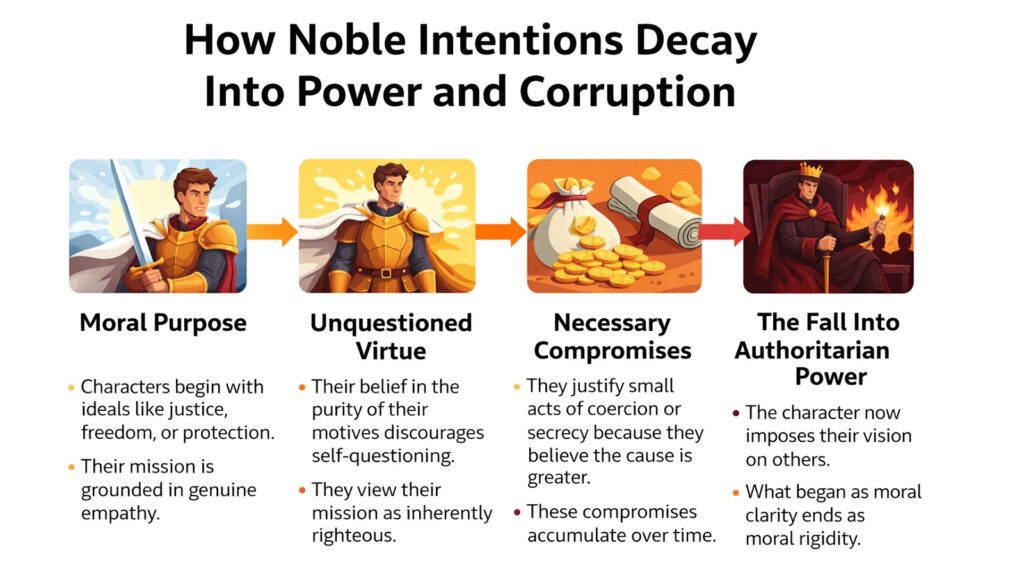

Good intentions can be a trap. Characters who start with strong moral convictions often believe their goodness protects them from corruption. They trust their own judgment too completely. This confidence becomes dangerous because it prevents self-examination. When someone is certain they are right, they stop looking for signs that they might be wrong. Their virtue turns into armor that blocks out criticism and reflection.

Literature shows how specific virtues can accelerate a character’s fall. Loyalty can make someone blind to the faults of those they serve. Idealism can justify cruelty when reality fails to match the vision. Kindness can evolve into paternalism, where a character decides what others need without asking them. These qualities start as strengths but become points of vulnerability. Power finds the cracks in moral certainty and widens them.

The psychological mechanism here is subtle. Characters believe their past goodness proves their current actions must also be good. They think their track record grants them permission to make harder choices. This creates a feedback loop. Each decision that violates their original principles feels justified because of who they used to be. The corruption happens in small steps, each one rationalized by the memory of earlier righteousness.

Power and Corruption: How Virtues Transform Into Vulnerabilities

| Initial Virtue | Corrupted Form |

|---|---|

| Compassion | Paternalistic control over others’ choices |

| Justice | Vengeful punishment without mercy |

| Dedication | Obsessive inability to admit failure |

| Selflessness | Martyrdom that demands others sacrifice too |

| Vision | Rigid ideology that crushes dissent |

| Courage | Reckless disregard for consequences |

2. Power and Corruption: The Seduction of Being Obeyed

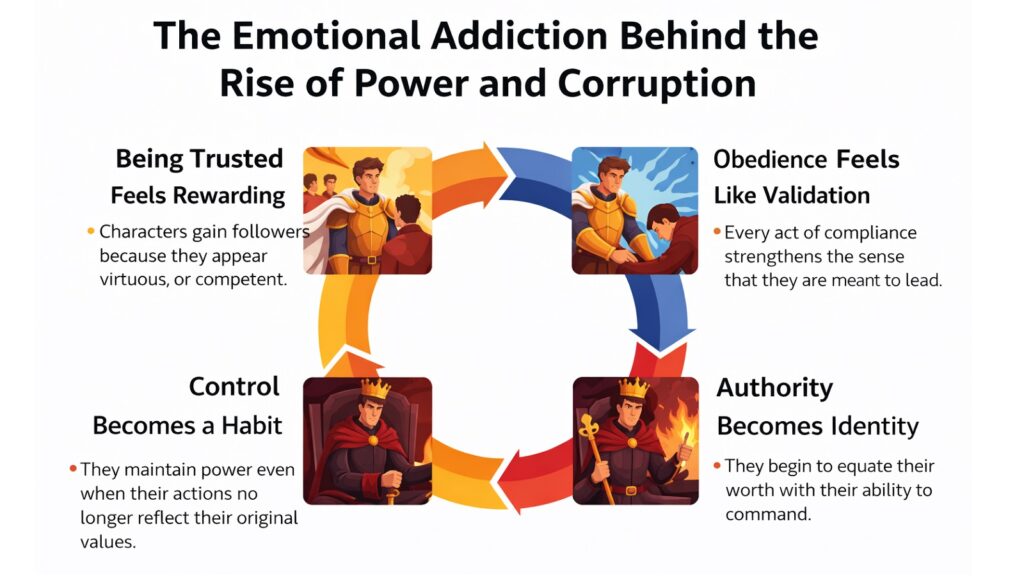

There is a specific pleasure in being followed. Characters who begin with humble goals often discover that authority feels good. People listen when they speak. Others seek their approval. Decisions get made because they made them. This emotional reward is subtle at first but grows stronger with repetition. The character starts to need that feeling of being trusted and obeyed.

Stories about Power and Corruption often show this transition through small moments. A leader makes a suggestion that becomes an order. A protector’s advice turns into a command. The character begins to expect compliance rather than request it. What started as service to others shifts into an expectation that others should serve them. The change happens gradually enough that the character does not notice they have stopped asking and started demanding.

This seduction is particularly effective because it disguises itself as validation. The character interprets obedience as proof that they are doing the right thing. If people follow them, they must be leading well. If no one objects, their choices must be correct. This creates a dangerous cycle where the character seeks more control to feel more validated. Authority becomes addictive. The need to be obeyed overtakes the original mission.

Power and Corruption: The Progression From Service to Dominance

| Stage | Character Behavior |

|---|---|

| Early Leadership | Suggests ideas and accepts input from others |

| Growing Authority | Expects agreement but allows mild disagreement |

| Comfortable Control | Becomes irritated when questioned or challenged |

| Entrenched Power | Interprets dissent as betrayal or ignorance |

| Full Dominance | Demands absolute obedience without explanation |

| Tyranny | Punishes any resistance as threat to order |

3. Power and Corruption: When “For the Greater Good” Justifies Harm

The phrase “for the greater good” signals danger in storytelling. It marks the moment when a character begins trading individual suffering for collective benefit. At first, the trade seems reasonable. One person’s discomfort might save many others. A small injustice might prevent a larger catastrophe. The character convinces themselves that the math makes sense. They calculate harm and decide some of it is acceptable.

This reasoning accelerates corruption because it removes moral boundaries. Once a character accepts that harming some people is justified, the only question becomes how much harm is necessary. The threshold keeps moving. What felt like a difficult exception becomes routine practice. The character stops seeing individuals and starts seeing obstacles or resources. People become variables in an equation rather than lives with inherent worth.

Literature uses this pattern to show how tyranny grows from moral compromise. Characters do not wake up one day and decide to become oppressors. They make one decision that violates their principles. Then another. Each choice feels necessary given the circumstances. The accumulation happens slowly enough that the character does not recognize how far they have traveled from their starting point. The greater good becomes a tool that justifies anything.

Power and Corruption: Escalation of Justified Harm

| Justification Phase | Action Taken |

|---|---|

| Initial Compromise | Accepts minor unfairness to achieve important goal |

| Expanded Exception | Causes deliberate harm to specific individuals |

| Systematic Harm | Creates policies that routinely damage vulnerable groups |

| Normalized Violence | Uses force as standard method of maintaining order |

| Institutionalized Cruelty | Builds systems designed to suppress and punish |

| Total Dehumanization | Views victims as deserving or necessary casualties |

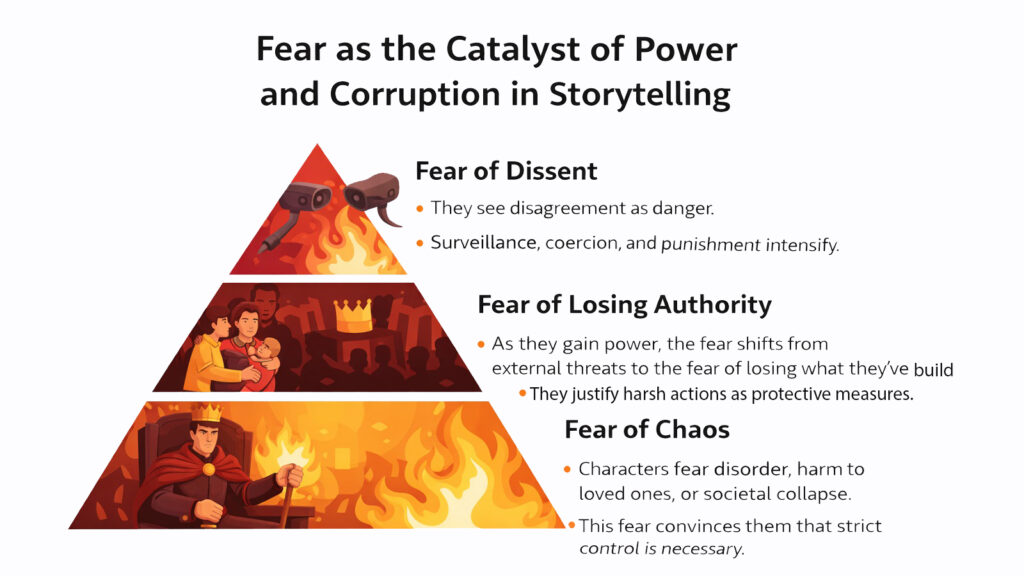

4. Power and Corruption: How Fear Turns Protectors Into Oppressors

Fear is a powerful catalyst for corruption. Characters who start as protectors often fall because they become terrified of loss. They fear betrayal from allies. They fear chaos if their control slips. They fear failure after investing so much. This fear does not make them weak. Instead, it makes them dangerous. Fear drives the need to eliminate uncertainty, which leads to tighter control over everything and everyone.

Stories show how fear transforms protective instincts into oppressive behavior. A character who wants to keep others safe begins to restrict their freedom. Someone afraid of betrayal starts surveilling their allies. A leader worried about dissent silences critics before they can speak. The character tells themselves this is still protection. They believe controlling others keeps them safe. But the line between guardian and jailer disappears.

This transformation works in fiction because it mirrors real psychology. When people feel threatened, they often try to control their environment. The more afraid they become, the more control they need. For characters with power, this means imposing order through force. Fear convinces them that any opposition increases danger. Compromise feels like weakness. Mercy seems like risk. The character becomes rigid, punishing, and isolated while still believing they are defending what matters.

Power and Corruption: Fear-Driven Transformation of Leadership

| Fear Type | Resulting Oppressive Behavior |

|---|---|

| Fear of Loss | Hoards resources and prevents others from leaving |

| Fear of Betrayal | Monitors allies constantly and punishes suspected disloyalty |

| Fear of Chaos | Enforces strict rules with harsh penalties for deviation |

| Fear of Weakness | Displays aggression to hide vulnerability or doubt |

| Fear of Replacement | Eliminates potential rivals or successors |

| Fear of Failure | Refuses to admit mistakes or change failing strategies |

5. Power and Corruption: The Moment a Character Believes They Alone Must Lead

A turning point in many corruption narratives comes when a character decides that only they can solve the problem. This belief might start from genuine capability. Perhaps they have succeeded where others failed. Perhaps they possess unique knowledge or skills. But this practical advantage evolves into something more dangerous. The character begins to think they are the only one who truly understands what needs to be done.

This “chosen one” mindset creates several problems. First, it breeds arrogance. The character stops listening to advice because they believe others cannot grasp the full picture. Second, it produces intolerance. Anyone who disagrees must be ignorant, corrupt, or weak. Third, it generates isolation. The character pulls away from allies because collaboration feels like compromise. They only associate with individuals who share their views completely.

Stories use this moment to show how corruption becomes self-sustaining. When a character believes they alone must lead, they interpret any resistance as a threat to the mission itself. They cannot separate their personal authority from the cause they serve. Criticism of their methods feels like an attack on the goal. This makes them increasingly rigid and hostile toward dissent. The character becomes unreachable, locked inside their own certainty.

Power and Corruption: Signs of Dangerous Exceptionalism

| Belief Pattern | Behavioral Manifestation |

|---|---|

| Unique Understanding | Dismisses others’ perspectives as incomplete or naive |

| Irreplaceable Role | Refuses to delegate or share decision-making power |

| Superior Morality | Judges others by standards they exempt themselves from |

| Prophetic Certainty | Treats their vision as inevitable and unquestionable |

| Burden of Isolation | Withdraws from relationships that challenge their views |

| Destiny Mindset | Believes their position proves they are meant to rule |

6. Power and Corruption: How Supporters and Systems Enable the Fall

Corruption rarely happens alone. Characters who fall into tyranny usually have help, even if that help is unconscious. Followers enable bad decisions by not questioning them. Institutions create structures that concentrate power. Allies excuse harmful behavior because they benefit from the character’s authority. Cultural norms make certain kinds of oppression feel normal or necessary. The system around the character shapes their fall as much as their own choices do.

Literature emphasizes this systemic element to show that Power and Corruption is not just about individual weakness. Stories examine how groups of people collectively allow or encourage someone to become a tyrant. Perhaps subordinates compete to show loyalty by carrying out harsh orders. Perhaps advisors rationalize cruelty as pragmatism. Perhaps the population accepts oppression because they fear chaos more. The character’s corruption becomes possible because others make space for it.

This perspective adds depth to corruption narratives. It shows that preventing tyranny requires more than strong individual character. Systems must include checks on power. Cultures must value dissent and questioning. Allies must be willing to oppose someone they respect when that person goes too far. Stories that highlight these systemic factors remind readers that responsibility for corruption spreads beyond the tyrants themselves.

Power and Corruption: How Systems and Supporters Enable Tyranny

| Enabling Element | Mechanism of Support |

|---|---|

| Loyal Subordinates | Execute harsh orders without moral resistance |

| Institutional Structures | Concentrate decision-making power without oversight |

| Cultural Narratives | Frame oppression as strength or necessary order |

| Economic Incentives | Reward those who support the regime with benefits |

| Silent Majority | Accepts tyranny through passive non-resistance |

| Propaganda Systems | Shape perception to justify authoritarian actions |

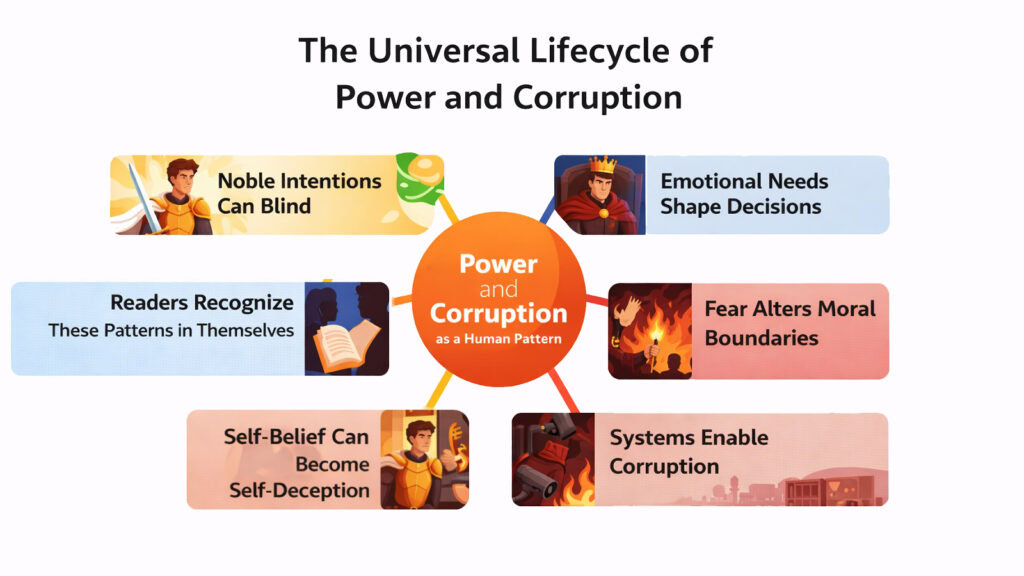

Conclusion: Power and Corruption – What These 6 Falls Teach Us About Human Nature

The theme of Power and Corruption endures because it tells uncomfortable truths about human nature. The stories covered here show that tyranny does not require evil intentions. It grows from unexamined virtues, from fear, from the seductive pleasure of being obeyed, and from systems that make abuse easy. Characters fall not because they are monsters but because they are human. They want to do good, feel validated, and maintain control. These ordinary desires become dangerous when combined with authority.

What makes these narratives frightening is their plausibility. Readers recognize the logic that corrupted characters use. We understand how someone could rationalize harm for a greater purpose. We see how fear might push us toward controlling behavior. We know the comfort of being right and the pain of admitting we were wrong. These stories work because they show us versions of ourselves, only a few steps further down a dangerous path.

The six patterns of the “Power and Corruption ” storytelling theme explored here overlap and reinforce each other. Virtue becomes weakness, which makes the character seek validation through obedience, which enables them to justify harm, which increases their fear, which makes them believe they alone can lead, which the systems around them support. Each element feeds the others. This interconnection is what makes corruption so difficult to resist and so common in both fiction and reality.

Stories about corrupted goodness serve as warnings. They remind us that moral certainty can be dangerous. They show us that good intentions do not guarantee good outcomes. They demonstrate that power changes people in ways they cannot always see from the inside. Most importantly, they teach us that the line between hero and tyrant is thin and often invisible. Anyone can cross it given the right circumstances and the wrong choices.

These narratives persist across cultures and time periods because they address a permanent human concern. As long as people have power over others, corruption will remain possible. As long as we struggle with fear, pride, and the desire for control, these stories will feel relevant. They do not offer easy answers, but they provide crucial questions. What would we do with authority? How would we handle fear? Could we recognize our own fall? The theme of Power and Corruption asks us to consider these questions before we ever face them in reality.

Power and Corruption: Literary Works Exploring the Theme

| Literary Work | Central Corruption Arc |

|---|---|

| Macbeth by William Shakespeare | Ambition and prophecy transform warrior into murderous tyrant |

| Animal Farm by George Orwell | Revolutionary ideals decay into totalitarian control |

| Lord of the Flies by William Golding | Civilized children descend into savage tribal violence |

| The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien | Ring’s influence corrupts even the most well-intentioned |

| Paradise Lost by John Milton | Satan’s pride and rebellion justify tyranny over hell |

| Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad | Colonial power corrupts Kurtz into brutal despot |

Read More Storytelling Article

- Franco Belgian Comics: 6 Powerful Storytelling Lessons

- Awakening Stories: 6 Powerful Cultural Archetypes

- Quest for Meaning: 6 Powerful Ways Stories Transform

- 6 Powerful Story Archetypes That Inspire Creativity

- 8 Storytelling Psychologies to Elevate Creative Edge

- 6 Amazing Ways Interactive Narratives Rewire Our Brains

- 6 Ways Graphic Narratives Whisper Silence and Trauma

- 6 Amazing Ways ‘Show Don’t Tell’ Engross Readers

- Explore Mahabharata’s 6 Genius Storytelling Techniques

- Iliad’s 6 Bold Storytelling Techniques That Grip You