Table of Contents

Introduction: Redemption and Forgiveness as a Universal Story Engine

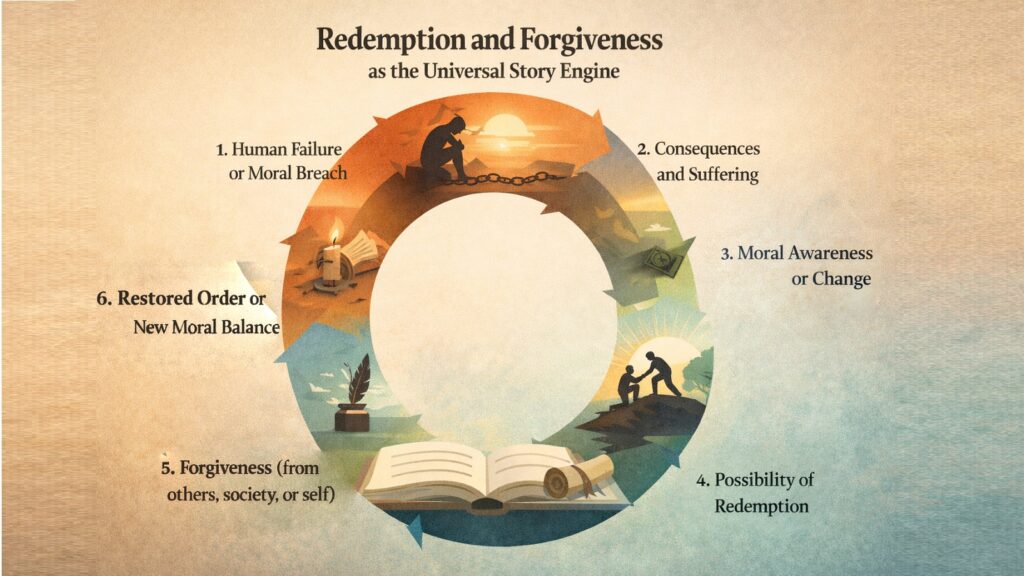

Stories endure as they pursue a shared yearning. We desire to observe an individual’s descent and subsequent ascent. We wish to see injuries heal or remain unhealed. Redemption and forgiveness are not merely moral framing in storytelling; rather, they function as the driving forces that propel characters through their journeys. They generate conflict between a person’s past self and their potential future self.

This theme works because it mirrors the contradictions we live with. People fail. People hurt others. The question is what happens next. Does the person change? Does the world let them back in? Redemption and forgiveness force stories to answer these questions, and the answers reveal how cultures think about responsibility, mercy, and transformation.

This article outlines six unique trajectories that narratives follow in their exploration of redemption and forgiveness. We will examine ancient epics in which redemption reinstates equilibrium, classical traditions that determine societal criteria for forgiveness, contemporary Western stories that depict internal transformation, narratives that distinguish redemption from reconciliation, tales in which sacrifice legitimizes change, and stories that pose the question to the audience without providing a definitive answer. None of these trajectories can be deemed correct or incorrect. Each one embodies a distinct perspective on the concepts of failure, transformation, redemption, forgiveness, and reintegration.

Redemption and forgiveness remain powerful because they operate at the intersection of individual choice and collective judgment. They ask whether change is possible and whether it matters if no one believes it. A story without the possibility of redemption feels static. A story without the complication of forgiveness feels shallow. Together, they create the friction that makes the narrative move.

Redemption and Forgiveness Compared to Other Major Storytelling Themes

| Storytelling Themes | Core Storytelling Function |

|---|---|

| Redemption and Forgiveness | Tests whether transformation is possible and whether society accepts it, creating tension between past actions and future identity |

| Survival | Strips characters to basic instincts, revealing core values under extreme pressure and resource scarcity |

| Good vs. Evil | Establishes moral clarity and forces characters to choose sides, simplifying conflict for emotional catharsis |

| Power and Corruption | Tracks how authority changes people, showing the gradual erosion of integrity under temptation |

| Destiny vs. Choice | Questions whether outcomes are predetermined or earned, creating suspense around agency and fate |

| Love and Loss | Explores emotional vulnerability and attachment, often serving as the catalyst for character decisions |

| Chaos vs. Order | Examines the structures that hold society together and what happens when they collapse or rigidify |

| Sacrifice and Duty | Sacrifice and duty give redemption moral weight and make forgiveness feel earned by showing that change requires personal cost and responsibility. |

1. Redemption and Forgiveness as Duty in Ancient Epics

Ancient epics treat redemption and forgiveness as necessary acts within a larger system. Characters do not seek redemption because they feel guilty in a modern sense. They seek it because they have disrupted cosmic order, offended the gods, or failed family obligations. When Achilles withdraws from battle in the Iliad, his anger creates disasters for the Greek army. His return is not about personal growth but about restoring his role in the collective effort.

Forgiveness operates as a ritual that repairs social bonds. When Odysseus returns home in the Odyssey, he proves his identity through knowledge only the real Odysseus would have. The story cares about order being returned, not about feelings being processed. This reflects cultures where individual identity is inseparable from family, tribe, or cosmic role. A person exists as part of a web, and when they break a thread, the whole structure suffers.

Redemption means mending that thread. The narrative stakes are high because failure affects everyone. Ancient epics often feature large-scale consequences for personal failures. One act of pride can lead to plague or war that touches entire communities. Characters demonstrate their redemption through deeds that restore balance. They make sacrifices, complete impossible tasks, or endure suffering. The audience watches to see if the character can fulfill what is required, not whether they can change their inner self.

Redemption and Forgiveness as Duty in Ancient Epic Storytelling

| Narrative Element | Function in Ancient Epics |

|---|---|

| Source of Wrongdoing | Disruption of cosmic order, familial obligation, or divine law rather than personal moral failure |

| Redemption Process | Restoration of role through action, sacrifice, or ritual that rebalances disrupted systems |

| Forgiveness Mechanism | Formal reintegration granted by community, family, or gods after proper restitution is made |

| Character Motivation | External pressure from consequences affecting the collective rather than internal guilt or conscience |

| Narrative Resolution | Return to harmony and proper function within the social or cosmic structure |

| Audience Expectation | Witnessing whether the character can fulfill required actions to restore their position and end collective suffering |

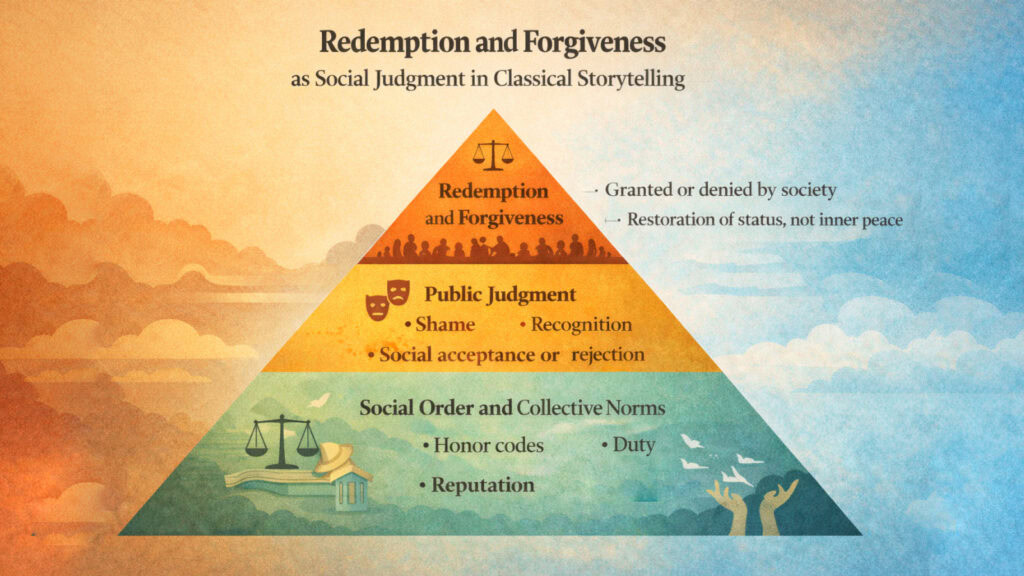

2. Redemption and Forgiveness as Social Judgment in Classical Traditions

Classical traditions shift the weight of redemption and forgiveness onto public opinion. Honor and shame become the currencies that determine whether a character can be redeemed. A person’s worth is measured by how others see them, and redemption only counts if society acknowledges it. Characters perform their transformation for an audience, knowing that internal change means nothing if it goes unrecognized.

Greek tragedy demonstrates this repeatedly. Characters face ruin not just because they do wrong but because their actions become public and destroy their reputation. Oedipus suffers from the exposure of his identity as the source of Thebes’ plague. His redemption in Oedipus at Colonus comes through exile and eventual sacred status, granted by the community that receives him. The story makes redemption a social event, not a private journey.

This framework creates specific tensions. Characters must navigate how they appear to others while managing what they actually did. The gap between public reputation and private reality drives the plot. Classical stories often end in tragedy because social forgiveness cannot be earned once certain lines are crossed. The community refuses reconciliation, and the character has nowhere to go.

Roman narratives add legal and civic structure. Redemption becomes tied to status, citizenship, and formal rehabilitation. A fallen nobleman might regain standing through military service. This reflects societies where law and public office carry immense weight. The emphasis on social validation creates suspense around whether the character can convince others that they have changed. Reputation itself becomes a character in the story, one that resists repair.

Redemption and Forgiveness Through Social Judgment in Classical Drama

| Narrative Element | Function in Classical Traditions |

|---|---|

| Source of Wrongdoing | Public exposure of actions that damage honor, reputation, or social standing within the community |

| Redemption Process | Visible acts performed for public validation, often requiring rhetorical skill or spectacular demonstration |

| Forgiveness Mechanism | Granted by society, civic institutions, or collective judgment rather than individuals or divine authority |

| Character Motivation | Restoration of honor and avoidance of shame through managing public perception and social standing |

| Narrative Resolution | Character either successfully rehabilitates their reputation or is destroyed by permanent social exclusion |

| Audience Expectation | Observing whether the character can persuade the community to accept their transformation and restore their place |

3. Redemption and Forgiveness as Inner Transformation in Modern Western Stories

Modern Western storytelling turns redemption inward. The emphasis shifts to psychological change. Characters seek redemption because they feel guilt, and they need forgiveness to achieve emotional closure. The narrative focus narrows to the interior landscape of the character’s mind. We watch them struggle with self-hatred, process trauma, or confront the gap between who they are and who they want to be.

This model treats redemption as a journey of self-discovery and moral reckoning. The character must acknowledge what they did wrong, understand why they did it, and change the patterns that led to the harm. Forgiveness becomes an emotional transaction between individuals. The person who was hurt must decide whether to grant forgiveness, and that decision carries its own narrative weight.

Films, novels, and television shows spend significant time inside the character’s head. We hear their thoughts, see their memories, and track their gradual realization of their own capacity for harm. A character might spend half the narrative in denial before reaching the moment where they see themselves clearly. This creates suspense around whether someone can bear to look at their own worst actions.

The emphasis on inner transformation changes what redemption looks like. In older traditions, redemption requires visible action. In modern Western stories, redemption often culminates in emotional honesty, a confession, or a choice to stop running from the past. The crucial shift happens internally. Forgiveness becomes complicated by the idea that no one is obligated to forgive. A character can achieve inner transformation and still be rejected by those they hurt.

Redemption and Forgiveness as Psychological Transformation in Modern Western Narratives

| Narrative Element | Function of Redemption and Forgiveness in Modern Western Stories |

|---|---|

| Source of Wrongdoing | Personal moral failure driven by psychological flaws, trauma, or destructive patterns within the individual |

| Redemption Process | Internal journey involving self-awareness, guilt, therapeutic insight, and deliberate behavioral change |

| Forgiveness Mechanism | Emotional decision made by individuals based on personal healing, with no obligation to grant it |

| Character Motivation | Relief from guilt, desire for self-acceptance, and need to repair emotional damage within relationships |

| Narrative Resolution | Emphasis on inner peace and psychological growth, whether or not external reconciliation occurs |

| Audience Expectation | Witnessing authentic emotional honesty and believing in the character’s capacity for genuine change |

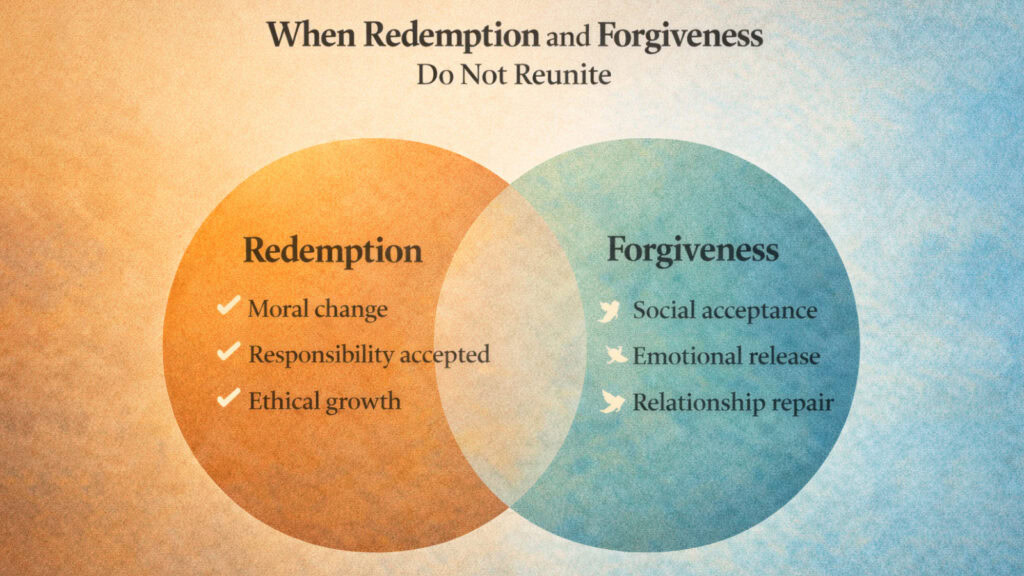

4. Redemption and Forgiveness Without Reconciliation

Some stories deliberately separate redemption from reconciliation. A character may change and become a better person, but the people they hurt refuse to welcome them back. This creates tension that acknowledges transformation does not erase harm. The character achieves moral progress but must live with permanent consequences. This approach adds weight by refusing easy resolutions.

These narratives often feel more realistic because they mirror how life works. People who cause deep harm can genuinely change, while those they hurt remain unwilling to forgive. The victim’s need for safety might override any recognition of the perpetrator’s growth. Stories that embrace this complexity avoid making redemption feel too simple or making forgiveness seem mandatory.

The narrative structure shifts the ending away from reunion. The character who sought redemption must find meaning in their transformation without external validation. They might help others, pursue a different path, or simply live with the knowledge that they became better even though it came too late. This creates a melancholy tone that can be more powerful than triumph.

Crime dramas feature criminals who reform but whose families refuse contact. War stories show soldiers who find peace but cannot return to their communities. Fantasy narratives include redeemed villains who fight alongside heroes but die before reconciliation can occur. The story honors both the reality of change and the legitimacy of ongoing hurt. This approach also reflects a shift in cultural thinking. Recent storytelling acknowledges that withholding forgiveness can be self-preservation rather than spite.

Redemption and Forgiveness When Reconciliation Fails in Storytelling

| Narrative Element | Function When Redemption and Reconciliation Split |

|---|---|

| Source of Wrongdoing | Harm severe enough that transformation cannot erase the damage or restore trust with those affected |

| Redemption Process | Genuine internal or behavioral change that occurs without external validation or acceptance from victims |

| Forgiveness Mechanism | Explicitly withheld by those harmed, validating their right to protect themselves despite perpetrator’s growth |

| Character Motivation | Finding meaning in change itself rather than expecting restoration of relationships or social position |

| Narrative Resolution | Character lives with permanent consequences while maintaining their transformation, creating bittersweet closure |

| Audience Expectation | Recognition that moral growth and social repair are separate processes, both valid in their own terms |

5. Redemption and Forgiveness Through Sacrifice and Loss

Narrative traditions across cultures use sacrifice to validate redemption. When a character seeking redemption loses something irreplaceable, the audience believes their transformation is real. The loss functions as proof that the change cost something. Stories structured this way create emotional weight through the currency of suffering. Redemption without cost feels cheap, while redemption earned through sacrifice resonates as authentic.

This pattern appears in heroic narratives where a character who failed others finds redemption by sacrificing themselves for the group. The sacrifice removes doubt about their sincerity. A character might spend an entire story trying to prove they have changed, but words leave room for skepticism. Death or permanent loss closes that gap. The audience sees that the character valued their redemption more than their survival.

The sacrificial model also addresses the problem of consequences. Sacrifice provides an answer by making the redeemed character pay a cost proportional to their wrongdoing. This satisfies a narrative sense of justice without requiring that the character be punished forever. They get to change, but they do not walk away unscathed.

Forgiveness in these stories often follows the sacrifice. The community grants forgiveness after witnessing what the character gave up. This creates a sequence where redemption earns forgiveness rather than hoping for it. The emphasis on loss creates a tragic dimension even in redemptive arcs. The character achieves moral victory but at the cost of everything they wanted. They save others but die in the process. This bittersweet quality makes the redemption feel more powerful because the story refuses to let the character have it all.

Redemption and Forgiveness Validated Through Sacrifice in Narrative Structure

| Narrative Element | Function When Sacrifice Validates Transformation |

|---|---|

| Source of Wrongdoing | Past harm serious enough that words or small actions cannot demonstrate genuine change to skeptical audiences |

| Redemption Process | Character proves transformation by accepting irreversible loss, often death, that benefits others or restores what they damaged |

| Forgiveness Mechanism | Granted after the sacrifice demonstrates the character valued redemption above self-preservation or comfort |

| Character Motivation | Desperate need to prove sincerity and repair harm, even at the cost of everything they have left |

| Narrative Resolution | Character achieves moral transformation but loses their life, relationships, or future, creating bittersweet catharsis |

| Audience Expectation | Belief in authenticity of change because the cost was proportional to the harm, satisfying both justice and mercy |

6. Redemption and Forgiveness Left to the Audience

Some narratives refuse to declare whether a character has achieved redemption or deserves forgiveness. The story presents the evidence and then steps back, leaving the judgment to each audience member. This technique creates lasting engagement because viewers continue debating long after the story ends. It also reflects a cultural move toward moral ambiguity and recognition that different people will reach different conclusions.

Stories built on this model often end at a moment of uncertainty. A character has taken steps toward change, but the transformation is incomplete. They have expressed remorse, but their actions have not caught up with their words. The people they harmed remain undecided. The narrative stops before resolution, creating a gap that the audience must fill with their own values.

This approach works particularly well in visual media where facial expressions and framing can suggest complexity without stating it. A character might look at someone they hurt with an expression that could be remorse or manipulation. Different viewers will read these moments differently based on their own experiences. The story becomes a mirror that reflects what each person brings to it.

The technique respects audience intelligence by refusing to resolve everything neatly. It acknowledges that moral questions often lack clear answers. This creates a more mature storytelling experience that trusts viewers to think. By leaving redemption and forgiveness open, the narrative forces each person to confront their own standards and examine why they believe what they believe about transformation and mercy.

Redemption and Forgiveness as Audience Judgment in Contemporary Storytelling

| Narrative Element | Function When Audience Decides Redemption |

|---|---|

| Source of Wrongdoing | Presented with sufficient complexity that multiple interpretations of motivation and severity remain valid |

| Redemption Process | Incomplete, ambiguous, or shown through actions that could indicate genuine change or continued manipulation |

| Forgiveness Mechanism | Deliberately unresolved within the narrative, transferred to individual audience members to decide based on their values |

| Character Motivation | Left partially opaque, allowing viewers to project either sincerity or deception based on their own instincts |

| Narrative Resolution | Ends before definitive judgment, creating a gap that invites ongoing interpretation and discussion |

| Audience Expectation | Required to engage actively with moral complexity rather than receiving clear guidance from the narrative structure |

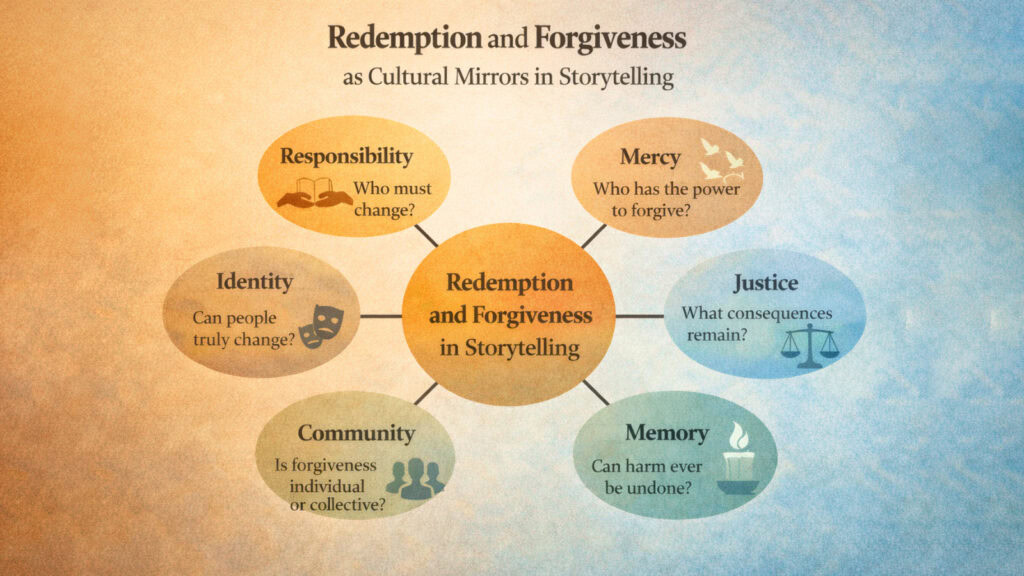

Conclusion: Redemption and Forgiveness as Cultural Mirrors in Storytelling

Redemption and forgiveness reveal how cultures understand responsibility, transformation, and mercy. Ancient epics tie redemption to duty and cosmic balance. Classical traditions place judgment in the hands of society. Modern Western narratives turn inward, locating redemption in psychological change. Some stories separate redemption from reconciliation entirely. Others demand sacrifice as proof of transformation. And some refuse to decide at all, leaving the question open for each person to answer.

The power of redemption and forgiveness as storytelling themes lies in their ability to create dramatic tension around questions that never settle. Can someone who did terrible things become good? Does it matter if they change if no one believes them? Should victims be expected to forgive? Stories explore these questions in endless variation. This is why the theme persists across centuries and borders.

As readers and viewers, we bring our own instincts to these stories. When we watch a character seek redemption, we measure them against our own standards. When we see someone withhold forgiveness, we decide whether they are protecting themselves or being cruel. These reactions come from our experiences with failure, betrayal, guilt, and grace. Stories about redemption and forgiveness work as diagnostic tools that help us understand what we believe about change and mercy.

The next time you encounter a story about redemption and forgiveness, notice how it shapes the path. Does it ask the character to restore order, win public approval, undergo inner transformation, live with rejection, sacrifice everything, or leave the answer uncertain? Notice also how you respond. Your answers will tell you something about the cultural narratives you carry and the standards you apply when judging whether people can leave their worst selves behind.

Redemption and Forgiveness Across Six Cultural Story Paths

| Story Path | Core Questions of Redemption and Forgiveness |

|---|---|

| Ancient Epic Duty Model | Can the character restore cosmic or social balance through action that fulfills their required role? |

| Classical Social Judgment Model | Can the character convince the community to restore their honor and accept their transformation publicly? |

| Modern Inner Transformation Model | Can the character achieve genuine psychological change and earn emotional closure with those they harmed? |

| Redemption Without Reconciliation Model | Can the character find meaning in transformation even when those they hurt refuse to grant forgiveness? |

| Sacrifice and Loss Model | Can the character prove their redemption is authentic by accepting irreversible cost or death? |

| Audience Judgment Model | Can you as the audience member decide whether this character deserves redemption and whether forgiveness should be granted? |