Table of Contents

Introduction: Understanding Sovereign Debt in Wealthy Nations

Sovereign debt sits at the heart of modern economics. It represents money governments borrow to fund operations, infrastructure, and social programs. For wealthy nations, this debt has ballooned to staggering levels. The paradox feels almost cruel. Countries with robust economies and strong currencies accumulate debt faster than struggling economies can dream of borrowing.

Global debt now exceeds 235 percent of world GDP according to the International Monetary Fund. Public debt alone approaches 93 percent of global output. These numbers tell a story of nations betting on tomorrow while mortgaging today. Wealthy countries enjoy advantages their poorer counterparts cannot access. Reserve currencies shield them from immediate consequences. Low interest rates have made borrowing seem almost free. Central banks print money with abandon.

Yet beneath this veneer of stability, cracks appear. Sovereign debt creates vulnerabilities even in the strongest economies. The United States, Japan, and European nations carry debt loads that would have seemed unthinkable decades ago. Currency dominance provides temporary immunity, not permanent protection. Monetary policy has limits that politics often ignores.

The six risks outlined here reveal how wealthy nations ignore warning signs. Excessive borrowing strains budgets. Rising interest payments consume resources. Growth becomes dependent on continued debt accumulation. Currency stability faces pressure. Investor confidence wavers. Long-term social implications mount. Each risk builds on the others, creating a web of interconnected vulnerabilities.

Understanding sovereign debt matters because its consequences touch everyone. Budget choices determine which programs receive funding. Interest rates affect mortgage payments and business loans. Currency values impact import prices. Market volatility shakes retirement accounts. The wealthy nations that dominate global finance cannot escape these realities through privilege alone.

Table 1: Sovereign Debt Relationships with Global Economic Factors

| Economic Factor | Relationship with Sovereign Debt | Key Dynamic |

|---|---|---|

| Global Economy | High sovereign debt constrains counter-cyclical policy responses during recessions | Debt-laden governments have limited fiscal space for stimulus |

| Global Trade | Debt levels influence currency valuations and trade competitiveness | Heavy borrowers may face currency depreciation affecting trade balance |

| Labor and Migration | Debt servicing competes with education and training investments | Budget constraints limit workforce development programs |

| Technology and Innovation | High interest payments reduce R&D and infrastructure spending | Debt obligations crowd out innovation investments |

| Natural Resources and Energy | Resource-rich nations with high debt face volatility in commodity prices | Revenue streams become unreliable for debt servicing |

| Governance and Institutions | Debt sustainability requires strong fiscal institutions and transparency | Weak governance exacerbates debt vulnerabilities |

| Global Supply Chain | Sovereign debt crises can disrupt trade finance and supply networks | Financial instability spreads through interconnected systems |

| Geopolitics | High debt levels constrain defense spending and diplomatic influence | Fiscal pressure limits international engagement capacity |

| Demographics | Aging populations increase social spending while tax bases shrink | Debt burdens intensify with unfavorable demographic shifts |

| Climate and Sustainability | Climate investments compete with debt obligations for limited resources | Transition financing faces constraints from existing debt |

1. Sovereign Debt Risk 1: Excessive Borrowing and Fiscal Pressure

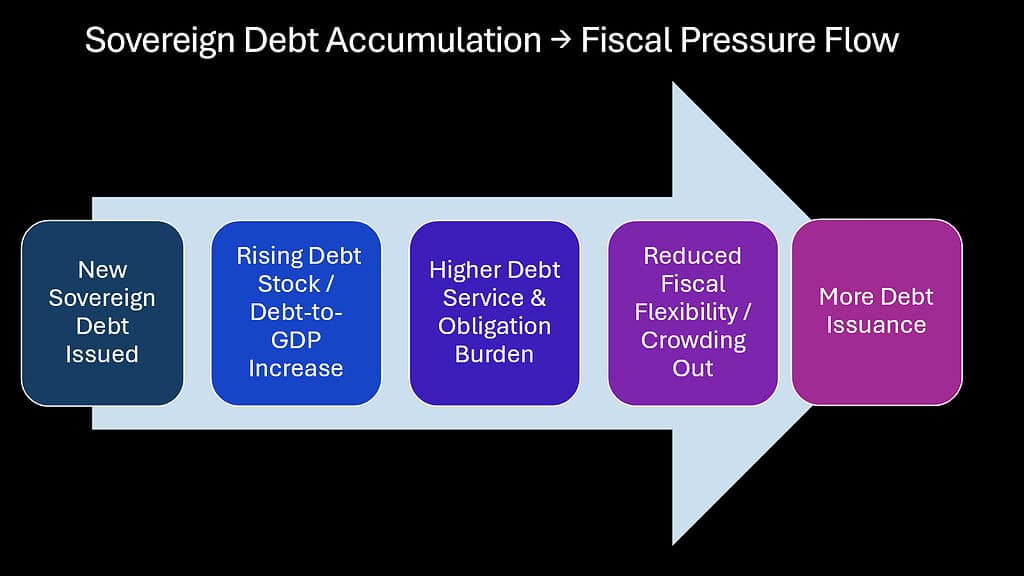

Governments face a simple truth. Every dollar borrowed today must be repaid tomorrow. Wealthy nations have tested this principle to breaking point. Continuous borrowing creates fiscal pressure that limits options. Budgets become rigid. Flexibility disappears. The ability to respond to crises diminishes with each passing year.

Japan leads developed nations with debt exceeding 236 percent of GDP according to Trading Economics data from 2024. This represents decades of deficit spending and stimulus programs. The United States follows with debt approaching 125 percent of GDP. The United Kingdom carries debt around 100 percent of its economic output. These ratios have climbed steadily for years.

Fiscal pressure manifests in multiple ways. Tax increases become necessary but politically difficult. Spending cuts face fierce resistance from beneficiaries. New programs struggle for funding. Infrastructure deteriorates while debt service demands grow. The budget becomes a zero-sum game where every winner creates losers.

The risks compound over time. Each year of deficit spending adds to accumulated debt. Interest obligations grow. The debt-to-GDP ratio rises unless economic growth outpaces borrowing. But relying on growth to solve debt problems creates another dependency. Economies cannot expand forever at rates sufficient to outrun mounting obligations.

Unchecked borrowing leads to crisis. History shows this pattern repeatedly. Greece discovered this during the European debt crisis. Argentina has defaulted multiple times. Venezuela collapsed under the weight of obligations it could not meet. Wealthy nations believe themselves immune to such outcomes. This belief may prove their undoing.

Table 2: Debt-to-GDP Ratios for Major Wealthy Nations (2024)

| Country | Debt-to-GDP Ratio | Data Source | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | 236.7% | Trading Economics (2024) | Highest among major developed economies |

| United States | ~125% | International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates (2024) | Rising trend continues post-pandemic |

| United Kingdom | ~100% | IMF/World Bank (2024) | Elevated from financial crisis response |

| France | ~110% | European fiscal data (2024) | Above EU Stability Pact threshold |

| Italy | ~140% | EU statistics (2024) | Consistently high within eurozone |

2. Sovereign Debt Risk 2: Rising Interest Payments and Budget Deficits

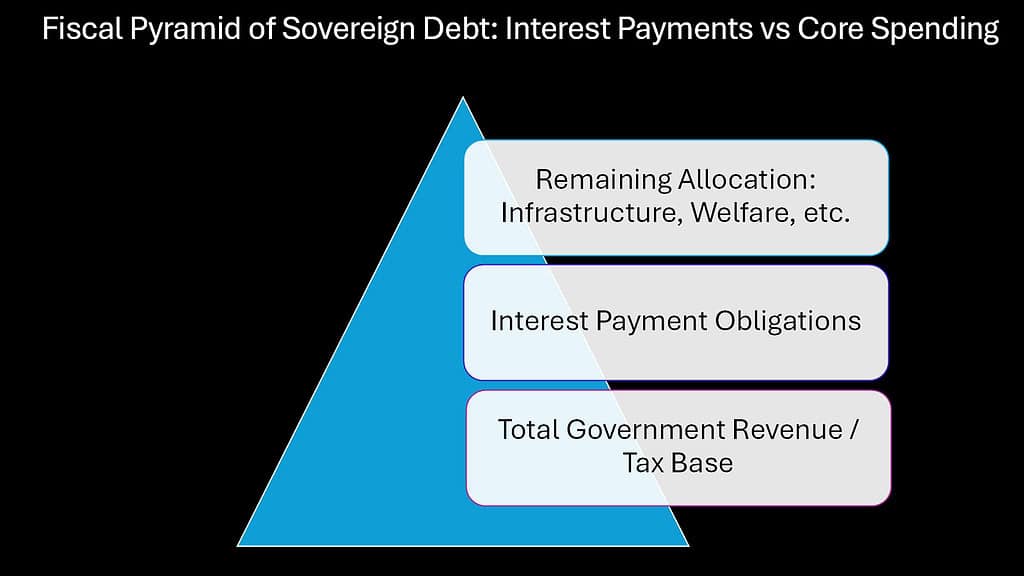

Interest payments devour government budgets. This reality grows harsher as debt accumulates and interest rates rise. The United States paid 892 billion dollars in net interest during fiscal year 2024 according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. This exceeded defense spending. Medicare costs less. The interest bill rose dramatically from 2023 levels.

These payments represent pure overhead. They buy no services. They build no roads. They feed no hungry children. Interest obligations simply service past decisions. The opportunity cost staggers the imagination. Nearly a trillion dollars flowing to bondholders instead of productive uses.

Budget deficits widen when interest costs rise. Governments must borrow more to pay interest on existing debt. This creates a vicious cycle. More borrowing generates more interest. More interest requires more borrowing. The spiral tightens with each turn. Breaking free becomes increasingly difficult.

Social programs face the axe first. Healthcare spending gets scrutinized. Pension benefits come under pressure. Education budgets shrink. Infrastructure projects get delayed or cancelled. Politicians claim fiscal responsibility while interest payments balloon. The productive capacity of the economy suffers as debt service crowds out investment.

The Federal Reserve’s interest rate policies compound these pressures. Higher rates combat inflation but increase government borrowing costs. A seemingly minor rate increase translates to billions in additional interest payments when debt reaches these levels. The Treasury must roll over maturing debt at higher rates. New borrowing carries steeper costs.

Table 3: Impact of Rising Sovereign Debt and Interest Payments on Government Budgets

| Impact Category | Description | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Crowding Out Effect | Interest payments compete with discretionary spending | Reduced funding for education, infrastructure, R&D |

| Fiscal Rigidity | Growing mandatory spending reduces budget flexibility | Limited ability to respond to emergencies or priorities |

| Intergenerational Transfer | Current consumption paid by future taxpayers | Younger generations inherit debt without benefits |

| Compounding Burden | Interest on interest accelerates debt accumulation | Exponential growth patterns emerge over time |

| Political Constraints | Sacred cow programs protected while others face cuts | Dysfunctional allocation of scarce resources |

3. Sovereign Debt Risk 3: Economic Growth Dependency on Debt

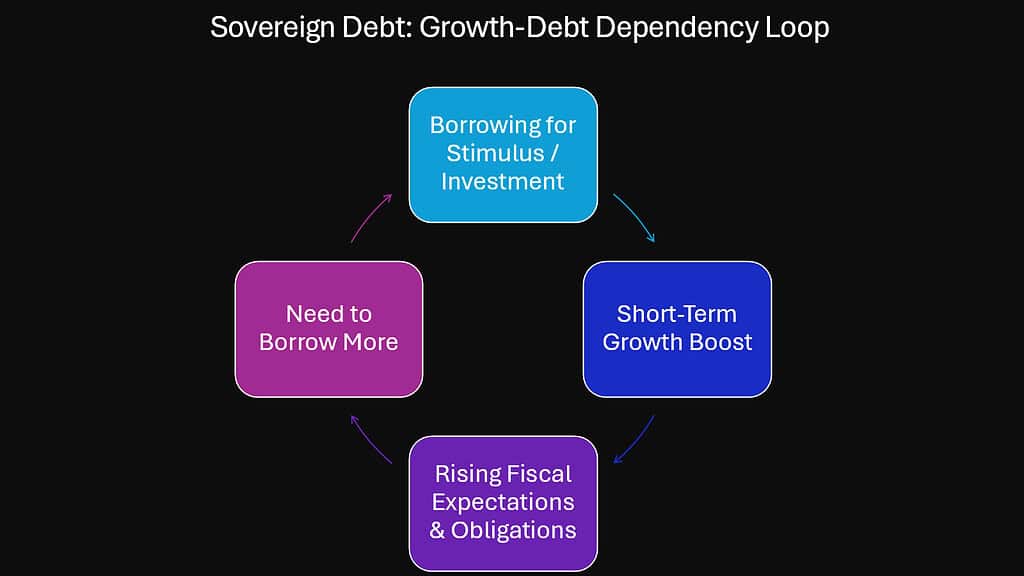

Modern economies run on borrowed money. This dependency creates fragility few acknowledge. Wealthy nations fuel growth through deficit spending rather than sustainable revenue. Tax cuts promise growth that rarely materializes sufficiently. Spending increases win political support. The gap gets filled with borrowed funds.

GDP growth obscures underlying weakness. Remove the fiscal stimulus and growth often disappears. Governments become addicted to spending they cannot afford. The economy grows accustomed to artificial support. Private sector activity adjusts to accommodate public sector deficits. When borrowing slows, recession threatens.

The pandemic revealed this dependency starkly. Governments borrowed trillions to support economies during lockdowns. Growth resumed as money flooded the system. Now inflation and interest rates rise while debt remains elevated. The bills come due, but the underlying economic strength never materialized. Governments cannot easily wean economies off fiscal support.

Sustainable growth requires productivity improvements and innovation. It demands investment in education and infrastructure. It needs competitive markets and efficient institutions. Debt-fueled growth substitutes borrowed consumption for genuine advancement. The economy appears healthy while fundamentals deteriorate. This illusion cannot persist indefinitely.

Japan’s experience illustrates the dangers. Decades of stimulus spending failed to generate sustainable growth. Debt mounted while the economy stagnated. Interest rates fell to zero, then went negative. Still, growth remained elusive. The debt burden became so large that escape routes disappeared. Other wealthy nations follow similar paths.

Table 4: Debt-Dependent Growth Patterns in Wealthy Nations

| Growth Pattern | Characteristic | Vulnerability |

|---|---|---|

| Fiscal Stimulus Reliance | Government spending drives GDP expansion | Growth collapses when stimulus withdrawn |

| Low Organic Growth | Private sector activity grows slowly without fiscal support | Structural weaknesses remain hidden |

| Productivity Stagnation | Innovation and efficiency gains fail to materialize | Long-term competitiveness erodes |

| Consumption vs Investment | Borrowed money funds consumption over productive investment | Future growth capacity diminished |

| Cyclical Vulnerability | Debt-fueled expansions create unsustainable booms | Subsequent contractions more severe |

4. Sovereign Debt Risk 4: Currency Vulnerability and Inflation Pressures

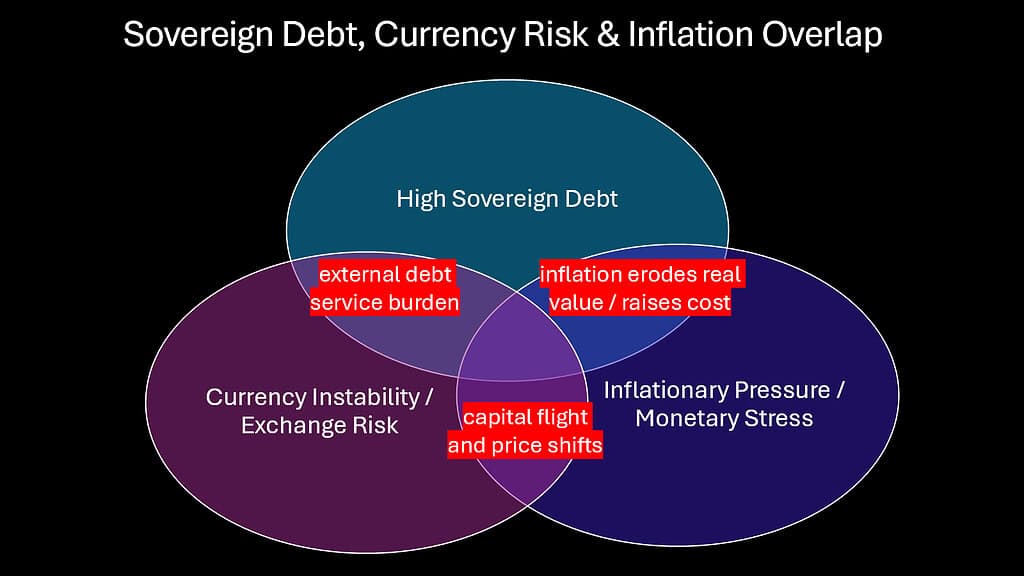

High sovereign debt threatens currency stability. This truth applies even to reserve currency issuers. The dollar’s dominance provides protection but not immunity. When debt reaches extreme levels, markets question sustainability. Currency values reflect these doubts. Inflation becomes harder to control.

Currency depreciation helps debtors through inflation. Governments with their own currencies can print money to service obligations. This dilutes the currency’s value. Bondholders receive repayment in debased currency. Real returns turn negative. The temptation to inflate away debt grows as burdens increase.

Britain’s experience during the 1970s demonstrates these risks. High debt combined with weak growth and poor productivity. The pound sterling collapsed. Inflation soared into double digits. The government sought IMF assistance. Once mighty Britain faced a financial crisis despite being a developed nation. Currency status provided no protection.

Japan navigates these waters differently. Despite massive debt, the yen remains relatively stable. Strong external balances and domestic bond ownership buffer the currency. But even Japan faces limits. As debt grows, the Bank of Japan must intervene constantly. Interest rates cannot rise without triggering a fiscal crisis. The currency becomes trapped by debt dynamics.

Inflation pressures build when debt limits monetary policy options. Central banks must choose between price stability and debt sustainability. Raising rates to combat inflation increases government interest costs. This forces difficult choices. Often inflation wins because default seems worse. Currency holders bear the cost through purchasing power erosion.

Table 5: Currency and Inflation Dynamics Under High Sovereign Debt

| Dynamic | Mechanism | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Inflation Tax | Governments reduce real debt burden through currency depreciation | UK in 1970s, persistent inflation eroded debt value |

| Monetary Policy Constraint | High debt limits central bank’s ability to raise rates | Japan maintains near-zero rates despite debt concerns |

| Currency Risk Premium | Investors demand higher yields for currency depreciation risk | Emerging markets face this constantly, now spreading to developed |

| External Balance Pressure | Trade deficits combined with high debt stress currencies | US twin deficits create long-term dollar vulnerability |

| Capital Flight | Investors move funds to stronger currencies as debt rises | Risk increases when fiscal sustainability questioned |

5. Sovereign Debt Risk 5: Reduced Investor Confidence and Market Volatility

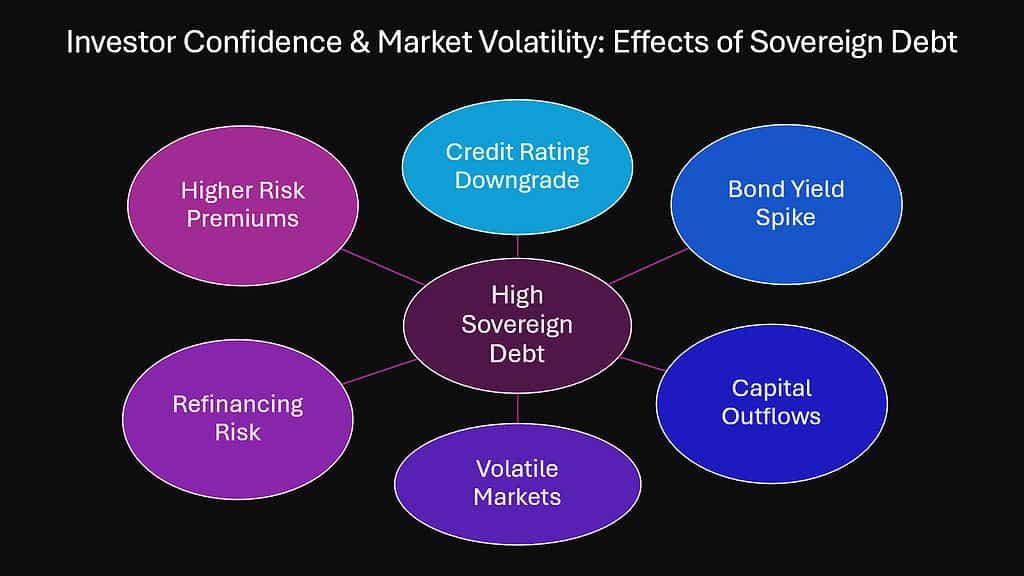

Markets watch sovereign debt levels carefully. Credit rating agencies assign grades that influence borrowing costs. Bond yields reflect perceived risks. When debt grows too large, confidence wavers. Investors demand higher returns for increased risk. Market volatility increases. Sudden swings become more common.

Standard and Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch rate sovereign creditworthiness. Investment grade status matters enormously. Falling below this threshold increases borrowing costs substantially. Japan maintains high ratings despite enormous debt because of domestic ownership and current account surplus. Other nations lack these advantages.

Bond yields tell the real story. When investors worry about repayment, they demand higher yields. Italy’s borrowing costs exceed Germany’s significantly despite both using the euro. The difference reflects perceived sovereign risk. Greek bonds once traded near German yields before crisis struck. Then spreads exploded as confidence collapsed.

Sovereign risk indicators track multiple factors. Debt-to-GDP ratios provide baseline measures. Deficit spending trends matter. Economic growth rates affect sustainability. Political stability influences confidence. External balances impact currency risk. These factors combine to shape market perceptions. Small changes can trigger large movements.

Market volatility creates real economic costs. Businesses delay investment during uncertain times. Consumers reduce spending. Capital flows become erratic. Refinancing debt grows expensive as yields spike. Governments find themselves at market mercy. The wealthy nation privilege of cheap borrowing disappears suddenly. Crisis can emerge from calm with shocking speed.

Table 6: Investor Confidence Indicators for Sovereign Debt

| Indicator | What It Measures | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Credit Ratings | Agency assessment of default risk | Determines investment grade status and borrowing costs |

| Bond Yield Spreads | Risk premium over benchmark securities | Reflects market’s real-time confidence level |

| Debt Rollover Ratio | Portion of debt requiring refinancing annually | High ratios create vulnerability to rate changes |

| Foreign Ownership Share | Percentage of debt held by non-residents | External holders more likely to flee during stress |

| CDS Spreads | Cost to insure against sovereign default | Market-based measure of perceived default risk |

6. Sovereign Debt Risk 6: Long-Term Social and Economic Implications

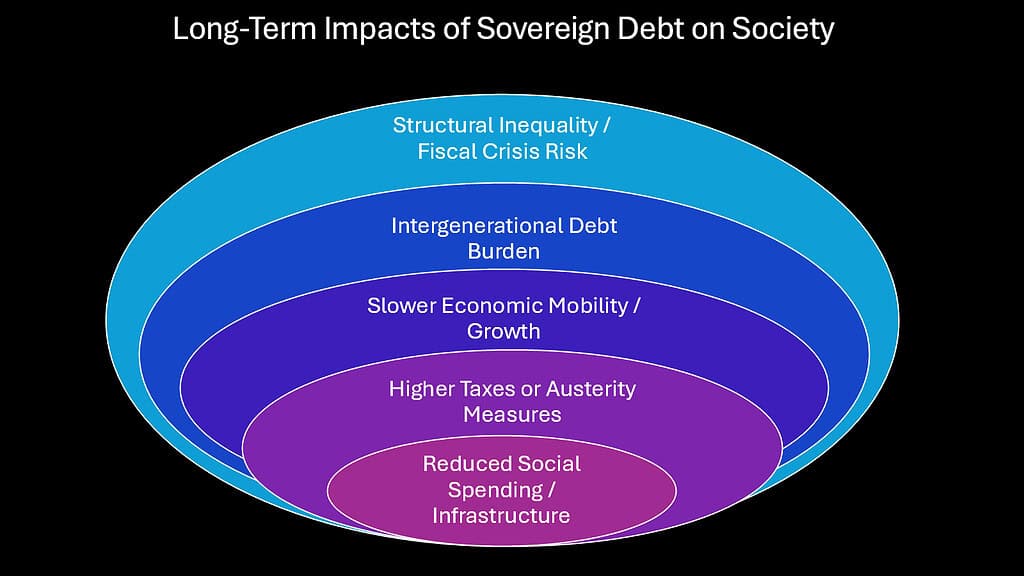

The future pays for present profligacy. This basic truth haunts sovereign debt discussions. Young people entering the workforce inherit obligations they did not create. Future taxpayers must service debt incurred for programs they never benefited from. This intergenerational transfer raises profound questions about fairness and sustainability.

Pensions face particular pressure from high sovereign debt. Government retirement programs promise benefits backed by future tax revenue. When debt service consumes growing portions of budgets, pension funding gets squeezed. Benefits may be reduced. Retirement ages rise. Younger workers pay more to receive less. Trust in social contracts erodes.

Healthcare systems struggle under dual pressures. Aging populations demand more services. Debt obligations limit available funding. Rationing becomes necessary. Wait times increase. Coverage shrinks. The quality of care deteriorates. Wealthy nations that pride themselves on healthcare access find promises impossible to keep.

Economic dynamism suffers from high sovereign debt. Research funding gets cut. Infrastructure crumbles. Education quality declines. These cutbacks reduce productivity growth. The economy’s potential shrinks. Future generations inherit not only debt but diminished capacity to service it. The burden compounds across time.

Social cohesion fractures when debt forces austerity. Different groups fight over shrinking resources. Young blame old for irresponsible borrowing. Recipients of government programs resist cuts. Taxpayers revolt against increased burdens. Political extremism grows. Democracy itself comes under stress. The social fabric that holds nations together weakens.

Even wealthy nations cannot escape these long-term implications. Their advantages delay reckoning but do not prevent it. The laws of mathematics and economics ultimately apply to everyone. Compound interest does not respect national boundaries or historical precedent. The bill arrives eventually.

Table 7: Long-Term Social and Economic Consequences of High Sovereign Debt

| Consequence | Impact Mechanism | Time Horizon |

|---|---|---|

| Pension Insecurity | Funding shortfalls lead to benefit cuts or delays | 10-30 years as obligations mature |

| Healthcare Rationing | Budget constraints limit medical spending growth | Ongoing and accelerating pressure |

| Infrastructure Decay | Deferred maintenance compounds into crisis | 20-50 year deterioration cycle |

| Educational Decline | Reduced investment in human capital | Generational impact on competitiveness |

| Innovation Deficit | R&D funding cuts reduce technological progress | Long-term productivity stagnation |

| Intergenerational Inequity | Young inherit debt without corresponding benefits | Permanent transfer across cohorts |

| Social Contract Breakdown | Lost faith in government promises | Political instability and extremism |

| Reduced Economic Mobility | Fewer opportunities for advancement | Entrenched inequality patterns |

Conclusion: Navigating Sovereign Debt Risks in Wealthy Nations

Sovereign debt presents challenges that wealthy nations can no longer ignore. The six risks outlined here form interconnected threats to economic stability and social wellbeing. Excessive borrowing constrains fiscal flexibility. Rising interest payments crowd out productive spending. Growth dependency on debt creates fragility. Currency vulnerability and inflation loom. Investor confidence wavers. Long-term social implications multiply.

These risks do not exist in isolation. They reinforce each other in dangerous ways. High debt increases interest costs. Higher interest costs require more borrowing. More borrowing raises sustainability concerns. Sustainability concerns undermine confidence. Lost confidence increases borrowing costs further. The cycle feeds itself.

Wealthy nations enjoy temporary advantages. Reserve currencies provide flexibility. Developed financial markets offer liquidity. Strong institutions maintain credibility. But advantages erode under mounting debt. History shows that privilege offers delay, not immunity. Economic laws eventually reassert themselves regardless of national status.

Policy responses require difficult choices. Raising taxes faces political resistance. Cutting spending hurts powerful constituencies. Growing out of debt demands productivity improvements that prove elusive. Inflating away obligations destroys credibility. Default remains unthinkable for major economies. Yet doing nothing guarantees eventual crisis.

Fiscal prudence seems boring compared to expansive programs and tax cuts. Politicians win elections with promises rather than restraint. Voters reward spending while punishing austerity. These incentives drive debt accumulation. Breaking this pattern requires leadership willing to prioritize long-term sustainability over short-term popularity.

Global cooperation offers part of the solution. Coordinated fiscal policies prevent races to the bottom. International institutions can support necessary adjustments. Knowledge sharing helps nations learn from each other’s experiences. But cooperation requires trust and shared purpose. These qualities seem scarce in current geopolitical climate.

Monitoring debt levels must become priority. Transparent reporting helps markets assess risks accurately. Early warning systems can identify problems before crisis strikes. Regular assessment of sustainability prevents complacency. Data-driven policy beats ideological rigidity. Evidence should guide decisions about borrowing and spending.

The path forward demands balancing growth with sustainability. Economic expansion remains important but cannot rely solely on debt accumulation. Investment in productivity matters more than borrowed consumption. Infrastructure, education, and innovation deserve priority. These investments generate returns that service debt while improving living standards.

Wealthy nations stand at a crossroads. They can continue current paths toward unsustainable debt levels. Or they can make hard choices to restore fiscal balance. The first option offers immediate gratification followed by eventual crisis. The second brings short-term pain for long-term stability. History will judge today’s decisions harshly if leaders choose poorly.

The alarm sounds clearly for those willing to listen. Sovereign debt risks are real even for prosperous nations. Ignoring warnings because of privilege or optimism invites disaster. The time for complacency has passed. Action becomes more urgent with each passing year. Future generations deserve better than the burden current policy creates.

Table 8: Policy Framework for Managing Sovereign Debt Risks

| Policy Area | Recommended Actions | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Fiscal Discipline | Establish binding debt targets and enforcement mechanisms | Gradual reduction in debt-to-GDP ratios |

| Revenue Enhancement | Broaden tax bases and improve collection efficiency | Sustainable funding without excessive borrowing |

| Spending Prioritization | Focus on productivity-enhancing investments | Higher growth potential improves debt sustainability |

| Monetary Policy Coordination | Align central bank and fiscal authority objectives | Balanced approach to growth and stability |

| Structural Reforms | Improve efficiency of government programs | Better outcomes with lower spending |

| Transparency and Reporting | Regular debt sustainability assessments | Early warning of emerging problems |

| International Cooperation | Coordinate policies to prevent competitive devaluation | Stable global financial system |

| Long-term Planning | Multi-decade frameworks for fiscal policy | Political insulation from short-term pressures |