Table of Contents

Introduction: STEM Learning Skills – Why Real Success Follows Hidden Patterns

Credit: iken3

Something puzzling happens in classrooms around the world. Two students sit through the same physics lecture. They receive identical problem sets in calculus. Both spend hours reviewing organic chemistry mechanisms. Yet one student grasps concepts quickly while the other struggles despite equal effort and intelligence.

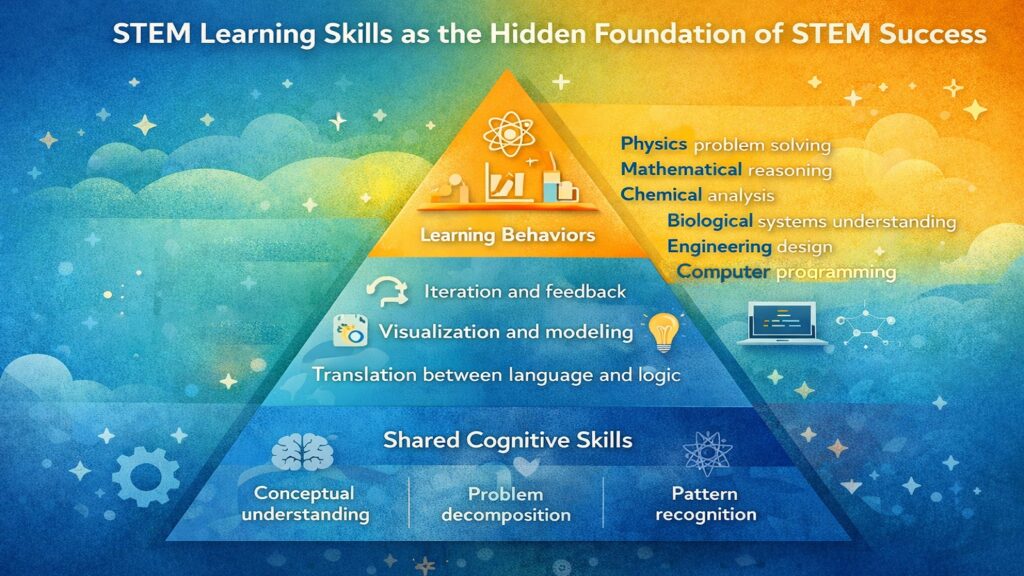

The difference rarely lies in subject-specific talent. Research from cognitive science laboratories reveals a different story. Success in Physics, Mathematics, Chemistry, Biology, Engineering, and Computer Science follows patterns that transcend individual disciplines. These patterns form what educators now recognize as transferable STEM Learning Skills.

Most learners approach STEM subjects as separate mountains to climb. They memorize formulas for physics, drill algorithms for computer science, and catalog reactions for chemistry. This fragmented approach misses a fundamental truth. Students who excel across multiple STEM fields share common mental habits. They think differently about problems. They process information through similar frameworks.

This article examines six powerful secrets behind internalizing STEM learning skills. These emerge from observation of high-performing learners, analysis of cognitive load research, and documentation of effective learning behaviors. Each secret represents a skill that transfers seamlessly from one STEM field to another.

Understanding these secrets behind STEM learning skills changes how we approach learning. A biology student who masters these skills finds organic chemistry less intimidating. An engineering student applies the same mental frameworks to computer programming. The skills compound over time, creating lasting competence rather than temporary memorization.

STEM Learning Skills Required Across Major Scientific Disciplines

| STEM Disciplines | Core STEM Learning Skills Required |

|---|---|

| Physics | Conceptual reasoning, mathematical modeling, spatial visualization, problem decomposition, pattern recognition in natural laws |

| Chemistry | Molecular visualization, reaction mechanism understanding, quantitative analysis, abstract reasoning, systematic experimentation |

| Biology | Systems thinking, pattern recognition in living processes, data interpretation, hierarchical organization, observational analysis |

| Mathematics | Logical reasoning, abstract thinking, proof construction, pattern identification, symbolic manipulation |

| Computer Science | Algorithmic thinking, abstraction, debugging methodology, logical decomposition, syntax-semantic translation |

| Engineering (General) | System decomposition, constraint analysis, iterative design, optimization thinking, practical application of theory |

| Environmental Science | Systems analysis, data synthesis, interdisciplinary thinking, temporal pattern recognition, causal reasoning |

| Data Science / Statistics | Pattern recognition in datasets, probabilistic thinking, model validation, quantitative reasoning, interpretation skills |

| Astronomy / Astrophysics | Scale reasoning, mathematical modeling, observational analysis, physical law application, spatial visualization |

| Robotics / Automation | Integration thinking, feedback loop analysis, system optimization, algorithmic implementation, sensor-actuator reasoning |

| Geology | Temporal reasoning, pattern recognition in Earth systems, three-dimensional visualization, process-oriented thinking |

| Microbiology | Microscopic systems thinking, experimental design, quantitative analysis, pattern recognition in cellular processes |

| Genetics | Information flow reasoning, pattern analysis in heredity, probabilistic thinking, molecular mechanism understanding |

| Neuroscience | Network thinking, signal processing concepts, interdisciplinary integration, experimental interpretation, systems analysis |

| Materials Science | Structure-property relationships, molecular visualization, quantitative analysis, optimization reasoning, experimental design |

| Marine Biology | Ecosystem thinking, adaptive reasoning, observational methodology, data collection strategies, environmental interaction analysis |

1. STEM Learning Skills: Conceptual Thinking Before Memorization

The strongest predictor of STEM success is not memory capacity. Studies tracking student performance reveal something counterintuitive. Learners who rush to memorize formulas often struggle when problems change format. Students who invest time in understanding underlying concepts solve unfamiliar problems with surprising ease.

Conceptual thinking means grasping why something works before worrying about calculations. In physics, this distinguishes students who understand conservation of energy as a fundamental principle from those who simply plug numbers into equations. The conceptual learner recognizes energy transformations across mechanical, thermal, and electromagnetic phenomena. The formula-focused learner freezes when problems deviate from textbook examples.

Mathematics education research documents this divide repeatedly. Students taught procedures without concepts can replicate worked examples but cannot adapt to novel situations. Those taught to understand mathematical structures develop problem-solving flexibility. They see calculus as the study of rates of change rather than derivative rules. They recognize linear algebra as the mathematics of transformations, not merely matrix operations.

Chemistry offers particularly clear examples. Memorizing that acids donate protons produces shallow knowledge. Understanding why electron distribution affects acidity creates deeper insight. When learners grasp electronegativity patterns and molecular structure relationships, they predict chemical behavior rather than recall it.

Computer science demonstrates the same principle through abstraction. Beginning programmers often memorize syntax and struggle when switching languages. Experienced programmers understand computational thinking concepts like loops, conditionals, and data structures. These concepts transcend specific programming languages.

Biology requires strong conceptual frameworks because living systems operate at multiple scales. Memorizing anatomical structures provides a limited understanding. Comprehending homeostasis, evolution, and cellular communication as organizing principles illuminates entire fields. A student who understands natural selection can reason through ecology, genetics, and behavior without memorizing isolated facts.

The cognitive mechanism behind conceptual learning involves building mental schemas. When learners construct robust conceptual models, new information integrates smoothly into existing frameworks. Memory becomes organized rather than fragmented. Problem-solving becomes reasoning rather than pattern matching.

STEM Learning Skills: Conceptual Understanding Versus Memorization Approaches

| Learning Approach | Outcome in STEM Disciplines |

|---|---|

| Memorizing physics equations without understanding | Cannot solve problems with unfamiliar contexts or variables; struggles with conceptual questions |

| Understanding energy conservation principles | Applies concepts across mechanics, thermodynamics, and electromagnetism; adapts to novel scenarios |

| Memorizing organic chemistry reactions | Forgets mechanisms quickly; cannot predict products for new reactions |

| Understanding electron flow and orbital theory | Predicts reaction outcomes; transfers knowledge to biochemistry and materials science |

| Memorizing calculus derivative rules | Fails when problems require conceptual interpretation or multiple-step reasoning |

| Understanding rates of change and limits | Applies calculus across physics, economics, and engineering; develops problem-solving intuition |

| Memorizing code syntax without logic | Struggles with debugging; cannot adapt when requirements change or languages switch |

| Understanding algorithms and data structures | Writes efficient code in any language; solves computational problems systematically |

2. STEM Learning Skills: Breaking Problems Into Smaller Systems

Credit: iken3

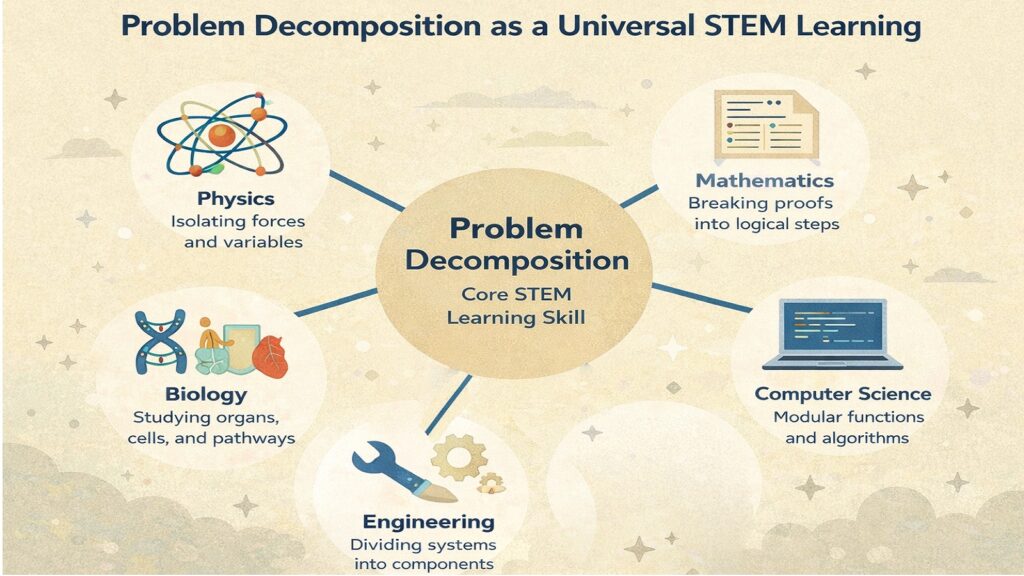

Complex problems paralyze many STEM learners. A multistep physics problem feels overwhelming. A lengthy proof seems impossible. High-performing students approach these challenges differently. They decompose complexity into manageable components.

Problem decomposition represents a fundamental cognitive strategy that successful learners apply universally. The specific techniques vary by discipline, but the underlying skill remains constant. Breaking systems into smaller parts reduces cognitive load and reveals solution pathways.

Engineers practice decomposition explicitly during design. A bridge becomes a structural element analyzed for specific loads. An aircraft separates into aerodynamic surfaces, propulsion systems, and control mechanisms. This modular thinking allows engineers to tackle enormous complexity by addressing one subsystem at a time.

Computer scientists build entire methodologies around decomposition. Functions encapsulate specific tasks. Classes organize related data and methods. This architectural thinking makes large software projects manageable. A programmer debugging complex code isolates individual functions, tests components separately, and verifies interfaces systematically.

Mathematicians decompose problems into lemmas and subproofs. A challenging theorem breaks into smaller claims, each proved independently before combining into a final argument. Algebraic problems separate into factorization, simplification, and solution steps.

Biology requires decomposition at multiple levels. Understanding human physiology means studying individual organ systems before examining interactions. Cellular biology examines organelles separately before considering cellular function holistically. Molecular biology reduces genetic processes to transcription, translation, and regulation as distinct mechanisms.

Physics problems naturally lend themselves to decomposition. Forces resolve into components. Complex motions separate into horizontal and vertical dimensions. Thermodynamic systems are divided into subsystems that exchange energy. Students who master this approach solve multistep problems efficiently.

Research in cognitive load theory explains why decomposition works. Working memory has a limited capacity. When problems exceed this capacity, comprehension deteriorates. Decomposition keeps cognitive demands within manageable limits. Each subsystem receives adequate mental resources for thorough processing.

STEM Learning Skills: Problem Decomposition Strategies Across Disciplines

| STEM Discipline | Decomposition Strategy Example |

|---|---|

| Mechanical Engineering | Breaking complex machines into subsystems (power transmission, control, structural support) for independent analysis |

| Software Development | Dividing programs into functions, classes, and modules that each handle specific tasks with defined interfaces |

| Organic Chemistry | Analyzing multi-step synthesis by examining each reaction mechanism separately before considering overall pathway |

| Physics Problem-Solving | Resolving forces into components, separating motion into dimensions, isolating energy transformations |

| Systems Biology | Studying metabolic pathways as connected reactions, each catalyzed by specific enzymes with individual kinetics |

| Mathematical Proofs | Breaking complex theorems into lemmas, proving smaller claims independently before combining results |

| Electrical Engineering | Analyzing circuits by examining individual components, nodes, and loops before synthesizing complete behavior |

| Environmental Science | Decomposing ecosystem analysis into population dynamics, energy flow, and nutrient cycling as separate processes |

3. STEM Learning Skills: Pattern Recognition Across Disciplines

Human brains excel at finding patterns. This cognitive strength becomes a powerful learning tool in STEM fields. Students who develop strong pattern recognition abilities learn faster and retain knowledge longer. They see connections that others miss.

Patterns appear everywhere in scientific disciplines. Physics reveals symmetries and conservation laws that repeat across phenomena. Chemistry shows periodic trends and reaction patterns. Biology displays evolutionary patterns and physiological cycles. Mathematics consists almost entirely of patterns made explicit through symbolic notation.

Physics education research demonstrates that pattern recognition separates novices from experts. Novices see individual problems as unique challenges. Experts recognize problem types and apply appropriate frameworks automatically. When an expert sees a mechanics problem, they immediately identify whether it involves energy conservation, momentum, or oscillation.

Chemistry’s periodic table represents pattern recognition made tangible. Elements in the same group share chemical properties because they have similar electron configurations. Students who recognize these patterns predict reactivity and bonding behavior without memorizing thousands of reactions. Organic chemistry becomes manageable when learners recognize functional group patterns and reaction mechanism types.

Biology depends heavily on recognizing patterns at multiple scales. Cell division follows predictable phases. Neural signals propagate through consistent mechanisms. Evolutionary adaptations produce similar solutions in unrelated species. Students who identify these patterns construct a coherent understanding rather than accumulating disconnected facts.

Computer science reveals patterns in algorithms, data structures, and design principles. Sorting algorithms share common strategies despite implementation differences. Experienced developers recognize when observer patterns, factory patterns, or strategy patterns solve design problems elegantly.

Engineering relies on recognizing patterns in system behavior. Feedback loops appear across control systems regardless of applications. Resonance phenomena occur in mechanical, electrical, and acoustic systems. Material properties follow patterns based on atomic structure and bonding characteristics.

Pattern recognition reduces cognitive load by chunking information. Instead of remembering thousands of isolated facts, learners store pattern templates that generate understanding on demand. Expert knowledge consists largely of rich pattern libraries accumulated through experience.

STEM Learning Skills: Common Patterns That Transfer Between Disciplines

| Pattern Types of STEM Learning Skills | Manifestation Across STEM Fields |

|---|---|

| Periodic Patterns | Chemical element properties, wave phenomena in physics, biological circadian rhythms, signal processing cycles |

| Hierarchical Organization | Biological taxonomies, mathematical proof structures, software architecture layers, engineering system levels |

| Symmetry Principles | Molecular geometry, physics conservation laws, mathematical group theory, crystal structures in materials science |

| Feedback Mechanisms | Homeostasis in biology, control systems in engineering, self-regulating chemical reactions, iterative algorithms |

| Exponential Growth/Decay | Population dynamics, radioactive decay, compound interest in applied math, signal attenuation in physics |

| Optimization Patterns | Natural selection in evolution, least-action principles in physics, efficiency in engineering design, algorithmic complexity |

| Network Structures | Neural connections, chemical reaction pathways, computer network topology, food webs in ecology |

| Conservation Laws | Energy and momentum in physics, mass conservation in chemistry, genetic information flow in biology, data integrity in computing |

4. STEM Learning Skills: Learning Through Feedback and Failure

Credit: iken3

Mistakes carry information. This principle distinguishes effective STEM learners from those who stagnate. When an experiment fails, skilled scientists analyze what went wrong. When code produces errors, competent programmers debug systematically. Each failure provides feedback that refines understanding.

Scientific progress itself depends on iterative refinement through failure. Laboratory experiments rarely succeed on the first attempt. Researchers adjust variables, modify procedures, and test alternatives based on previous results. Students who embrace this process during learning develop genuine scientific thinking.

Chemistry laboratories provide constant feedback. Reactions produce unexpected products. Measurements deviate from predictions. Each discrepancy demands explanation. Students who treat these failures as puzzles to solve develop chemical intuition.

Physics problem-solving offers immediate feedback through self-checking. Negative masses, speeds exceeding light, and energies violating conservation laws signal errors. Strong students recognize these impossible results as valuable information. They trace backward through calculations and verify reasoning.

Computer programming consists almost entirely of iterative debugging. Code rarely runs correctly initially. Experienced programmers welcome error messages as diagnostic tools. They read stack traces, test edge cases, and isolate problematic code sections.

Engineering education explicitly teaches iteration through failure. Design projects go through multiple prototypes. Each version reveals flaws that inform improvements. Students learn that initial designs always need refinement.

Cognitive science research on learning supports this approach. Studies show that retrieval practice with feedback produces stronger learning than passive review. The effort to recall information, discover errors, and correct misunderstandings strengthens memory and understanding.

The key distinction lies in how learners interpret failure. Those with growth mindsets view mistakes as information about current understanding and opportunities for improvement. This interpretation dramatically affects learning outcomes across all STEM disciplines.

STEM Learning Skills: Feedback Mechanisms That Drive Learning Progress

| STEM Domain | Feedback Method and Mechanism of STEM Learning Skills |

|---|---|

| Laboratory Chemistry | Yield calculations and product analysis reveal technique effectiveness and conceptual understanding of reactions |

| Physics Problem Solving | Impossible results (negative mass, excessive speed) indicate calculation errors or conceptual misunderstanding requiring analysis |

| Software Development | Compiler errors, runtime exceptions, and failed tests pinpoint specific issues in code logic and implementation |

| Mathematical Proofs | Logical inconsistencies and counterexamples expose flawed reasoning and guide correction of proof structure |

| Engineering Prototypes | Performance measurements and stress tests reveal design weaknesses requiring iterative modification |

| Biological Experiments | Unexpected organism responses or null results indicate confounding variables or flawed experimental design |

| Data Analysis | Model validation metrics and cross-validation reveal overfitting, bias, or inappropriate model selection |

| Scientific Research | Peer review, replication attempts, and anomalous results provide critical feedback that refines theories and methods |

5. STEM Learning Skills: Visualization and Mental Modeling

Abstract concepts become concrete through visualization. This transformation enables understanding that words and equations alone cannot provide. Successful STEM learners develop strong visualization skills that they apply across different disciplines.

Physics relies heavily on visual reasoning. Vector diagrams represent forces, velocities, and fields. Free-body diagrams isolate objects and show all forces acting on them. Students who draw these representations solve problems more accurately than those who work purely with abstract equations.

Molecular visualization revolutionized chemistry education. Three-dimensional models of molecules reveal bond angles, stereochemistry, and reactive sites that structural formulas obscure. Students who build and manipulate molecular models develop intuition about chemical behavior that memorization cannot provide.

Biology depends on visualization at every scale. A diagram of a cell shows organelle relationships. Anatomical illustrations reveal organ structures. Metabolic pathway maps connect biochemical reactions. These visual representations organize enormous complexity into comprehensible formats.

Mathematics becomes visual through graphs and geometric representations. Functions plotted on coordinate systems reveal behavior that equations hide. While mathematics ultimately rests on logical rigor, visualization provides crucial intuition that guides formal reasoning.

Computer science uses flowcharts, state diagrams, and algorithm visualizations. These tools make abstract computational processes concrete. Data structures become visual objects with clear relationships. Debugging becomes easier when programmers visualize program flow.

Engineering disciplines employ extensive visualization tools. CAD software renders three-dimensional designs. Circuit diagrams represent electrical systems. Finite element analysis visualizes stress distributions. These tools transform abstract specifications into concrete representations.

The act of creating visualizations forces clarity. A vague understanding becomes obvious when attempting to draw a diagram. This forcing function identifies gaps in knowledge that passive reading might miss.

Mental models extend visualization beyond external diagrams. Experienced scientists develop rich internal simulations of systems. A physicist imagines particle trajectories. A chemist visualizes electron redistribution. These internal models enable prediction and problem-solving without external aids.

STEM Learning Skills: Visualization Tools and Their Applications

| Visualization Type | Application Across STEM Fields |

|---|---|

| Diagrams and Schematics | Circuit analysis in electrical engineering, reaction mechanisms in chemistry, anatomical systems in biology |

| Graphs and Plots | Function behavior in mathematics, experimental data in physics, population dynamics in ecology |

| Three-Dimensional Models | Molecular structures in chemistry, protein folding in biochemistry, mechanical assemblies in engineering |

| Flowcharts and State Diagrams | Algorithm design in computer science, process flows in chemical engineering, physiological pathways in biology |

| Vector Representations | Force analysis in mechanics, electric fields in physics, velocity fields in fluid dynamics |

| Network Diagrams | Neural connectivity in neuroscience, food webs in ecology, circuit topology in electronics |

| Heat Maps and Contours | Electron density in chemistry, temperature distribution in thermodynamics, gene expression in molecular biology |

| Simulation Visualizations | Molecular dynamics in chemistry, structural stress in engineering, population models in biology |

6. STEM Learning Skills: Translating Between Language and Logic

STEM disciplines communicate through multiple languages simultaneously. Natural language describes phenomena. Mathematical notation expresses relationships precisely. Chemical formulas represent molecular structures. Code implements algorithms. Successful learners move fluidly between these representational systems.

This translation skill creates a major divide in STEM classrooms. Some students read a physics problem and immediately construct mental models with relevant equations. Others struggle to extract mathematical meaning from verbal descriptions. The difference lies not in mathematical ability but in translation competence.

Physics word problems challenge students precisely because they require translation. A paragraph describing motion must become velocity vectors and kinematic relationships. Students who translate accurately solve problems efficiently.

Mathematics education research identifies translation as a persistent difficulty. Students learn to manipulate equations but struggle when problems arrive in words. They can differentiate functions but cannot identify when rates of change appear in applied contexts.

Chemistry requires translating between names, formulas, structures, and reaction equations. A verbal description of a synthesis must become structural formulas showing electron flow. Students who master these translations navigate organic chemistry successfully.

Biology uses specialized vocabularies that require careful translation. Genetic information flows from DNA to RNA to protein, but understanding this requires translating between sequence notation, biochemical structures, and cellular processes.

Computer science demands constant translation between human-readable descriptions and executable code. Algorithm descriptions become functions with loops and conditionals. Programmers who translate accurately write correct code efficiently.

Engineering specifications arrive as verbal requirements with performance criteria. These must translate to mathematical constraints and design parameters. A bridge must support specific loads translates to stress calculations and structural dimensions.

The cognitive challenge involves maintaining meaning through translation. Students often lose information when moving between representations. Skilled learners maintain semantic connections across representational modes.

Successful STEM learners develop translation habits. They read problems multiple times, extracting different information with each pass. They annotate problems with diagrams and symbols. They verify that translations preserve meaning by checking units, magnitudes, and physical plausibility.

STEM Learning Skills: Translation Requirements Between Representational Systems

| Translation Challenge | STEM Context and Requirement |

|---|---|

| Verbal to Mathematical | Converting physics word problems describing motion into kinematic equations with correct variables and signs |

| Mathematical to Verbal | Explaining what a derivative means in practical terms of rates of change in applied science contexts |

| Structural to Symbolic | Translating drawn chemical structures to systematic nomenclature and molecular formulas with correct stereochemistry |

| Algorithmic to Code | Converting pseudocode descriptions of computational procedures into syntactically correct programming implementations |

| Data to Graphical | Transforming numerical datasets into appropriate visualizations that reveal patterns and relationships |

| Graphical to Mathematical | Extracting equations and parameters from plotted data in experimental sciences |

| Requirements to Specifications | Translating engineering design requirements in natural language to quantitative technical specifications |

| Biological Process to Model | Converting verbal descriptions of physiological systems into mathematical models with differential equations |

Conclusion: STEM Learning Skills – How These 6 Secrets Create Lasting Success

Credit: iken3

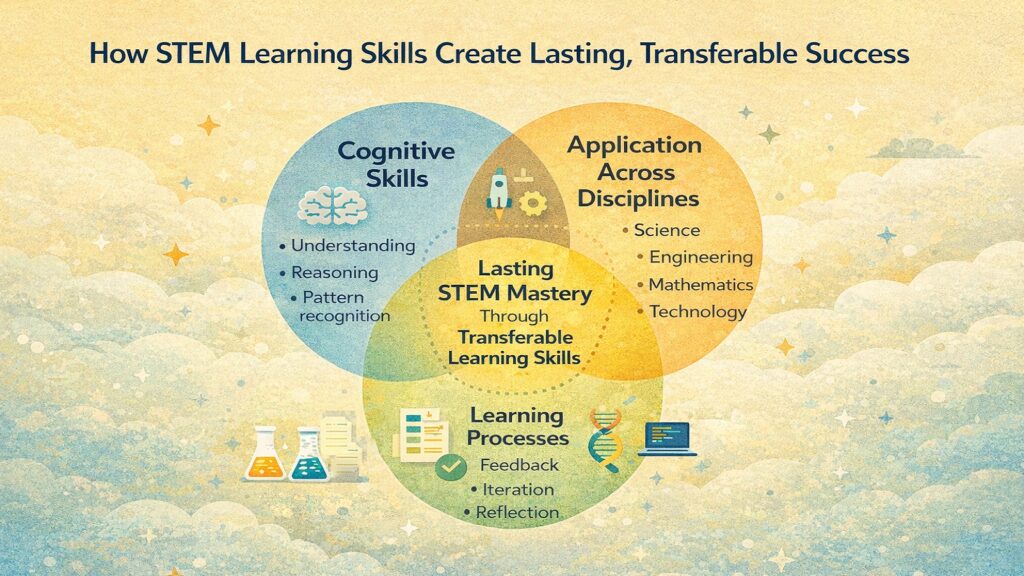

These six secrets of STEM learning skills create an integrated framework rather than isolated techniques. Conceptual thinking provides the foundation. Decomposition manages complexity. Pattern recognition accelerates learning. Feedback refines understanding. Visualization makes abstractions concrete. Translation connects different ways of knowing. Together, they constitute the deep structure of STEM competence.

Students who develop these STEM learning skills transcend subject boundaries. A biology student applies decomposition to analyze metabolic pathways and uses the same skill to debug code. An engineering student employs pattern recognition in structural analysis and transfers it to circuit design. The skills compound across disciplines.

Research in cognitive science consistently validates this skills-based approach. Studies tracking long-term academic success show that learning skills predict performance better than prior knowledge. Students who enter courses with strong STEM Learning Skills outperform peers with better content preparation but weaker learning strategies.

The transferability of STEM learning skills explains why some students excel across multiple STEM fields. Natural talent matters less than systematic approaches to learning. Intelligence provides raw capacity, but learning skills determine how effectively that capacity gets deployed.

These six secrets of STEM learning skills also explain why cramming produces temporary performance but poor retention. Memorization without conceptual understanding creates fragile knowledge. Problem-solving without decomposition produces cognitive overload. Learning without feedback perpetuates misconceptions. Sustainable success requires building genuine competence through proper learning skills.

The encouraging implication is that STEM Learning Skills are transferable and can be mastered. They develop through deliberate practice rather than innate talent. Students who currently struggle can adopt these approaches and transform their learning effectiveness.

These STEM Learning Skills create lasting success because they address how understanding actually forms in human minds. They align with cognitive architecture rather than fighting against it. They transform STEM education from a gauntlet that eliminates students into a pathway that develops capability.

STEM Learning Skills: Integration Framework for Sustained Excellence

| Learning Skill Combination | Synergistic Effect on STEM Competence |

|---|---|

| Conceptual Thinking + Pattern Recognition | Enables rapid identification of underlying principles in new contexts and immediate classification of problem types |

| Decomposition + Visualization | Transforms overwhelming complexity into manageable visual components that can be analyzed systematically |

| Feedback Analysis + Conceptual Understanding | Converts mistakes into precise corrections targeting actual misconceptions rather than surface errors |

| Translation + Mental Modeling | Allows seamless movement between verbal, visual, and symbolic representations while maintaining coherent understanding |

| Pattern Recognition + Decomposition | Identifies recurring structures within complex systems and reveals efficient solution pathways |

| Visualization + Translation | Bridges abstract symbols and concrete meanings through external representations that clarify relationships |

| All Six Skills Combined | Creates self-reinforcing learning cycle where each skill strengthens others and compounds over time |

| Sustained Practice Across Disciplines | Develops transferable expertise that adapts to new STEM fields and accelerates mastery of emerging topics |

Read More Science and Space Articles

- Universe Odyssey: 8 Essential Stages Of A Remarkable Journey

- Cosmic Giants: 8 Incredible Titans Shaping Our Universe

- Cosmic Forces: 8 Powerful Phenomena Shaping Our Universe

- God: 6 Powerful Scientific Insights That Reveal Human Belief

- Hawking Radiation: 6 Powerful Clues to Quantum Gravity

- Black Hole Singularity: 6 Mind-Blowing Truths Explained

- 6 Incredible Ways Missiles Obey The Laws of Physics

- Millisecond Pulsars: 6 Incredible Insights Driving Science