Table of Contents

Introduction: The Psychology of Subtext in Storytelling

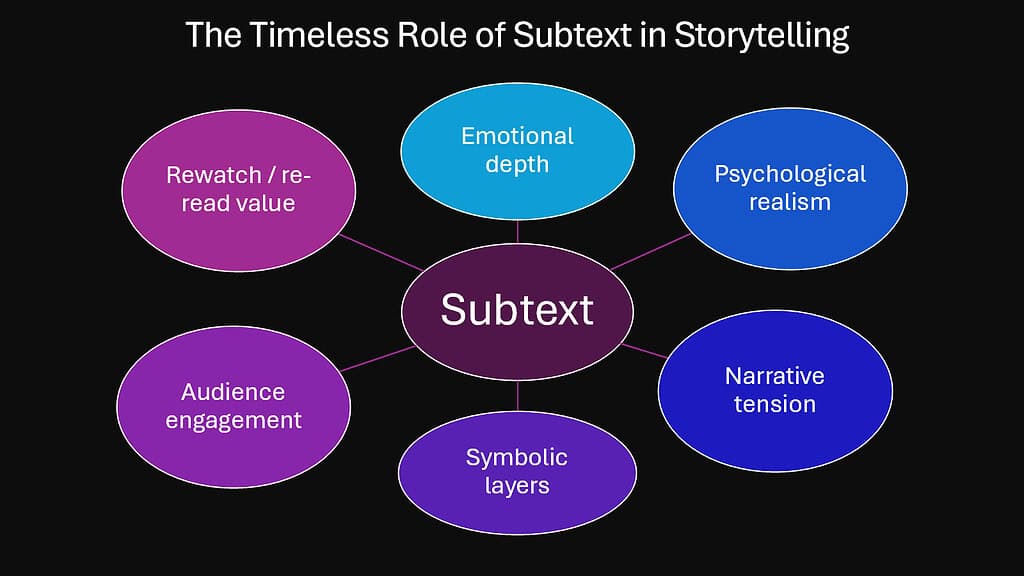

Every great story holds two narratives. One lives on the surface, spoken through dialogue and action. The other breathes underneath, carried through silence, gesture, and the weight of what remains unsaid. This hidden layer is subtext, and it stands as one of the most powerful storytelling psychologies available to writers.

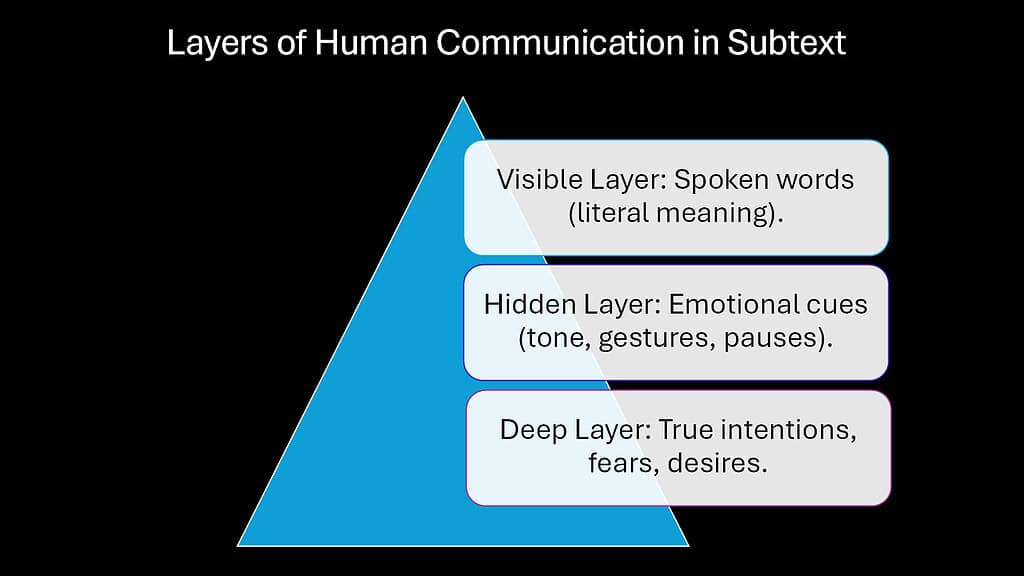

Subtext works because it mirrors how humans actually communicate. We rarely say exactly what we mean. A compliment might carry jealousy. A question might hide an accusation. When someone says they’re fine, they might be breaking inside. Writers who master this technique tap into this fundamental truth about human nature. They create characters who feel real because they behave like real people, hiding fears and desires beneath polite conversation.

Readers are drawn to hidden meaning because discovery feels rewarding. When we uncover what a character truly feels beneath their words, we become active participants rather than passive observers. Subtext creates emotional depth by adding layers that resonate long after the story ends. It transforms simple exchanges into complex psychological portraits. The surface meaning entertains us, but the buried meaning haunts us.

This article explores six brilliant examples of subtext across film and literature. From Casablanca to Get Out, these stories demonstrate how this technique operates across genres and eras. Each example reveals different techniques for embedding hidden meaning into dialogue, silence, and behavior. Writers who study these examples gain tools to elevate their own storytelling from competent to unforgettable.

Before diving into specific examples, it helps to understand where subtext fits among other storytelling psychologies. Each technique serves different purposes, but subtext offers unique advantages in creating layered meaning.

Table 1: Subtext Compared to Other Storytelling Psychologies

| Storytelling Psychologies | Primary Function | Reader Experience | Subtext’s Distinction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrative Hook | Captures immediate attention through compelling opening | Creates instant curiosity and engagement | Subtext builds gradual discovery rather than immediate impact |

| Emotional Arc | Maps character’s emotional journey from beginning to end | Provides satisfying transformation and growth | Subtext adds hidden emotional layers beneath visible arc |

| Mirror Effects | Reflects reader’s own experiences and emotions | Creates personal connection and recognition | Subtext requires interpretation, making discovery feel earned |

| Plot Twists | Subverts expectations through surprise revelations | Delivers shock and recontextualization | Subtext offers continuous layered meaning rather than single revelation |

| Worldbuilding | Establishes setting, rules, and cultural context | Provides immersive environment and believability | Subtext operates through character psychology rather than external world |

| Suspense | Builds anticipation through delayed resolution | Creates tension and keeps readers engaged | Subtext works through implication rather than explicit setup |

| Moral Framing | Establishes ethical questions and themes | Guides reader toward philosophical reflection | Subtext embeds meaning subtly rather than stating themes directly |

1. Subtext Magic in Casablanca: Love and Loss Beneath Words

Rick Blaine repeats a simple phrase throughout Casablanca that carries an ocean of unspoken emotion. When he tells Ilsa, “Here’s looking at you, kid,” the words seem casual, almost throwaway. Yet each repetition adds weight, accumulating meaning like sediment building into rock. The phrase begins as playful affection in their Paris flashbacks, transforms into bitter nostalgia in their Casablanca reunion, and finally becomes a tragic farewell when Rick sends her away.

Director Michael Curtiz and screenwriters Julius and Philip Epstein understood that the most profound emotions often hide behind the simplest words. Rick never declares his devastation at being abandoned in Paris. He never explicitly states that his cynicism masks heartbreak. He never announces that sacrificing Ilsa for the resistance breaks him again. The phrase does all this work through accumulation and context. Each time Rick says those words, we hear everything he cannot say.

The subtext operates on multiple levels simultaneously. On the surface, Rick appears tough and indifferent. He claims to stick his neck out for nobody. Yet his actions contradict his words at every turn. This gap between what Rick says and what Rick does creates dramatic irony that audiences find irresistible. We know his heart before he admits it to himself. When he finally helps Victor Laszlo escape with Ilsa, the subtext becomes text, but the emotional payoff only works because of the buried longing we’ve sensed throughout.

Casablanca demonstrates how subtext transforms familiar dialogue into memorable art. Many characters in many films say goodbye to lost loves. Few goodbyes carry the weight of Rick’s final scene with Ilsa because few films build such careful layers of unspoken emotion. The techniques here remain relevant for modern writers. Simple repeated phrases gain power through context. Characters who hide emotions create depth. Contradictions between words and actions reveal truth more effectively than exposition.

Table 2: Layers of Meaning in Rick’s Signature Phrase

| Context of Usage | Surface Meaning | Subtext Layer | Emotional Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paris flashback scenes | Playful toast between lovers | Expression of genuine intimacy and hope | Establishes their authentic connection before tragedy |

| Rick’s Cafe confrontation | Bitter acknowledgment of shared past | Weaponized nostalgia expressing betrayal | Shows pain masked as detachment |

| Airport sacrifice scene | Final farewell gesture | Acknowledgment of enduring love despite loss | Transforms bitterness into noble heartbreak |

| Throughout repeated usage | Casual affectionate expression | Shield protecting vulnerability from exposure | Creates pattern revealing character defense mechanism |

2. Subtext Magic in The Godfather: Civility as Menace

Don Corleone speaks with impeccable politeness when he explains that he will make someone an offer they cannot refuse. The words sound almost friendly. He frames his threats as favors, his violence as reasonable business. This gap between courteous delivery and brutal meaning defines the Mafia’s power in Francis Ford Coppola’s masterpiece. The Godfather family never shouts or threatens directly. They smile while destroying lives.

Mario Puzo’s novel and Coppola’s screenplay understand that true power whispers rather than yells. When Don Corleone discusses business, he uses euphemism and indirection. People who cross him simply disappear. Horses’ heads appear in beds without explanation. The family discusses murder over pasta dinners with the same tone others use for weather. This calculated understatement makes the violence more disturbing rather than less. The subtext screams what the dialogue refuses to acknowledge.

The famous phrase about offers that cannot be refused works because it sounds like generosity, while meaning coercion. Don Corleone presents himself as a helper solving problems. Only through subtext do we understand that he creates the problems he claims to solve. His courteous tone implies that violence is simply an unfortunate consequence of someone else’s poor choices. This rhetorical sleight of hand shifts blame while maintaining his civilized facade.

Modern crime dramas learned from The Godfather that an unstated threat carries more weight than explicit menace. When powerful people speak in code, they demonstrate their power through the very act of coding. Only the powerless must speak plainly. The Corleones signal their dominance through their ability to avoid directness. Everyone understands what they mean without them needing to say it. This remains relevant for writers creating any character with power, whether criminal, political, or social.

Table 3: Subtext as Power Dynamic in The Godfather

| Dialogue Pattern | Literal Meaning | Underlying Threat | Power Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Requests framed as favors | Suggesting mutual benefit | Implying consequences of refusal | Creates false choice while maintaining polite surface |

| Business euphemisms for violence | Discussing professional matters | Normalizing murder as transaction | Removes moral weight through linguistic distancing |

| Family-focused rhetoric | Emphasizing loyalty and protection | Demanding absolute obedience | Uses intimacy language to justify control |

| Quiet measured tone | Projecting calm reasonableness | Demonstrating confidence in inevitable compliance | Shows power through lack of need to raise voice |

3. Subtext Magic in Lost in Translation: Silence That Speaks

Ernest Hemingway believed the best writing resembled an iceberg, with most meaning hidden beneath the surface. He called this the Iceberg Theory, suggesting that writers should omit information to strengthen stories. Sofia Coppola applies this principle masterfully in Lost in Translation when Bob whispers something to Charlotte at the film’s end. We never hear his words. The camera pulls away. The moment exists entirely as subtext.

This final whisper carries the entire emotional weight of their relationship. Throughout the film, Bob and Charlotte struggle to articulate their connection. He faces a midlife crisis in a foreign country. She questions her marriage and identity. They find unexpected understanding in each other, but their circumstances make any conventional resolution impossible. The whisper becomes everything they cannot say, everything the relationship means despite its impossibility.

Hemingway’s theory suggests that readers feel more when writers show restraint. Coppola proves this by denying audiences the one thing they most want to hear. Countless viewers have tried to read Bob’s lips or enhance the audio. This frustration becomes part of the experience. We lean forward, straining to catch the words, exactly as Charlotte leans in to hear them. The film makes us feel her hunger for connection by creating our own hunger for information.

The subtext works because the specific words matter less than the gesture itself. Bob returns to find Charlotte. He crosses through Tokyo crowds to say goodbye properly. The whisper represents acknowledgment, closure, and intimate understanding. Whatever he actually says, the meaning remains clear. Some connections transcend circumstances even when circumstances prevent their full expression. Writers can learn from this restraint. Sometimes the most powerful moments come from what we choose not to reveal.

Table 4: Hemingway’s Iceberg Theory Applied to Lost in Translation

| Visible Element (Above Surface) | Hidden Element (Below Surface) | Effect on Audience |

|---|---|---|

| Brief Tokyo encounter between strangers | Profound existential loneliness and search for meaning | Creates emotional resonance through recognition of universal isolation |

| Unclear words in final whisper | Acknowledgment of impossible love and meaningful connection | Generates active interpretation and personal investment |

| Casual conversations about mundane topics | Deep philosophical questions about identity and purpose | Allows viewers to project their own existential concerns |

| Cultural displacement and jet lag | Fundamental disconnection from one’s own life | Makes literal displacement metaphor for emotional state |

| Platonic friendship maintained | Unspoken desire and romantic possibility | Creates tension through what remains unacted upon |

4. Subtext Magic in Pulp Fiction: Banter as Veiled Tension

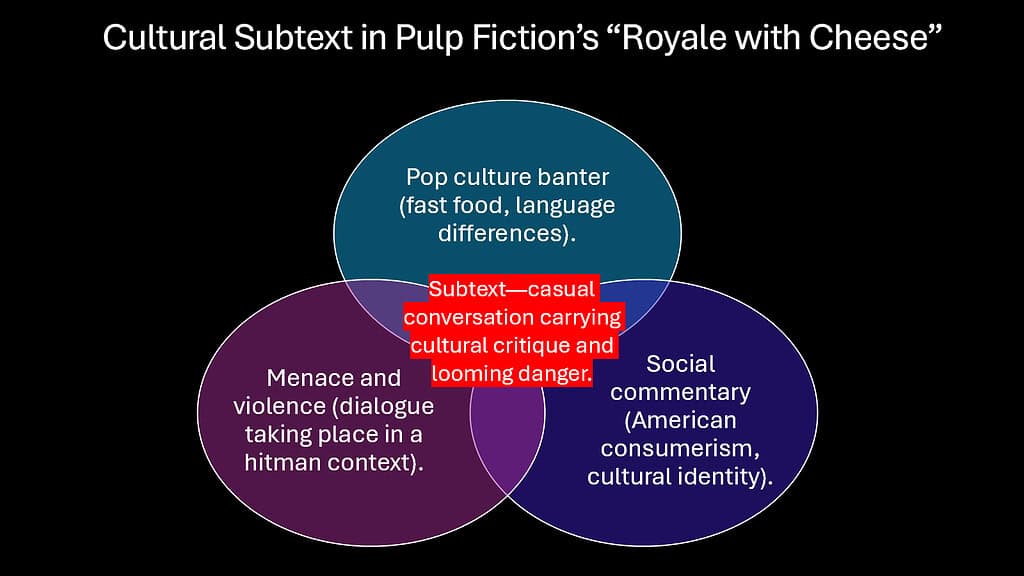

Vincent and Jules discuss hamburgers while driving to commit murder. They debate whether a Quarter Pounder with Cheese becomes a Royale with Cheese in France due to the metric system. Quentin Tarantino fills this seemingly trivial conversation with layered subtext about culture, class, and casual violence. The ordinariness of their banter while approaching extraordinary violence creates a disturbing contrast.

The dialogue works on multiple levels simultaneously. On the surface, two coworkers chat about fast food. Slightly beneath, the conversation reveals class differences and cultural awareness. Jules traveled to Europe and noticed how American products adapt abroad. Vincent stayed American and remains provincially unaware. This small detail sketches entire worldviews. Deeper still, the casual tone while approaching a hit normalizes violence. These men discuss hamburgers because murder has become so routine that it requires no emotional preparation.

Tarantino understood that subtext often emerges from a mismatch between tone and situation. Most films about hitmen would show them psyching themselves up or discussing strategy. Pulp Fiction subverts this by making violence just another day at work. The burger conversation becomes more disturbing than any amount of tough-guy posturing precisely because of its mundanity. The subtext screams about moral numbness, while the text discusses mayonnaise.

This technique remains influential because it reveals character through unexpected juxtaposition. Writers often make the mistake of having characters discuss what they’re about to do. Tarantino shows that characters reveal more by discussing anything except what they’re about to do. The avoidance itself becomes revealing. Normal people would be nervous before violence. Vincent and Jules chat about metric systems. This gap tells us everything about who they’ve become through their profession.

Table 5: Layers of Subtext in the Royale with Cheese Scene

| Dialogue Layer | Content Focus | Character Revelation | Thematic Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface conversation | Fast food menu differences in France | Jules’s worldliness versus Vincent’s provincialism | Establishes character contrast through mundane topic |

| Cultural observation | American versus European standards | Awareness of cultural relativity and adaptation | Suggests broader themes about perspective and context |

| Class marker | Who travels internationally versus who doesn’t | Economic and experiential differences between them | Adds dimension to their professional partnership |

| Tonal dissonance | Casual chat before commission of violence | Complete moral desensitization to their profession | Creates disturbing normalization of extraordinary acts |

5. Subtext Magic in A Streetcar Named Desire: Desire and Denial

Blanche DuBois insists on soft lighting throughout Tennessee Williams’s play. She avoids bright bulbs, preferring dimness and shadows. She claims this preference as simple vanity about her aging appearance. Freudian psychoanalysis reveals much deeper subtext. Sigmund Freud argued that the unconscious mind hides uncomfortable truths from consciousness through defense mechanisms. Blanche’s obsession with light becomes an elaborate metaphor for her desperate denial of reality.

Williams creates a character drowning in repression. Blanche lost her family estate, Belle Reve, which translates from French as beautiful dream. She worked as a teacher until the scandal destroyed her reputation. She engaged in affairs seeking connection, but found only deeper shame. Now she arrives at her sister Stella’s home in New Orleans, clinging to aristocratic pretensions that no longer match her circumstances. Every refined gesture and cultured reference functions as a defense against acknowledging what she has become.

Freud identified several defense mechanisms the ego uses to protect itself. Blanche employs nearly all of them. She uses denial, refusing to acknowledge her drinking or her past. She employs projection, accusing others of qualities she possesses. She relies on repression, burying traumatic memories beneath performative gentility. Most significantly, she uses sublimation, channeling sexual desire into elaborate romantic fantasies. Her constant references to death and desire reveal the unconscious breaking through despite her efforts.

The light itself becomes Freud’s unconscious made visible on stage. Harsh light reveals truth. Darkness permits fantasy. Blanche desperately controls the lighting because she desperately controls what can be seen and acknowledged. When Stanley finally tears the paper lantern off the light bulb, he symbolically strips away her defenses. The subtext becomes text in that brutal moment, but the power comes from Williams building the metaphor carefully throughout. Modern writers can learn how physical details become psychological revelation through consistent symbolic development.

Table 6: Freudian Defense Mechanisms as Subtext in Streetcar

| Defense Mechanism | Blanche’s Behavior | Surface Explanation | Subtext Revelation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denial | Refuses to acknowledge alcoholism and past | Claims refined ladies drink occasionally | Unconscious rejection of trauma and loss |

| Projection | Accuses others of vulgarity and baseness | Maintains aristocratic superiority | Displaces her own shame onto others |

| Repression | Avoids discussing husband’s suicide | Presents herself as tragic widow | Buries guilt and unresolved trauma |

| Sublimation | Romanticizes strangers as potential saviors | Expresses need for protection and love | Channels sexual desire into fantasy of rescue |

| Reaction Formation | Performs exaggerated refinement and modesty | Displays Southern belle propriety | Overcompensates for sexual history and scandal |

6. Subtext Magic in Get Out: Horror Beyond the Surface

Jordan Peele’s Get Out transforms social horror into literal horror through brilliant deployment of subtext. When white characters tell Chris, “I would have voted for Obama for a third term” or ask, “Is it better?”, they believe they’re demonstrating progressive values. The subtext reveals something far more sinister. These microaggressions function as coded power assertions disguised as friendliness.

Peele understands that modern racism rarely announces itself through explicit slurs. Instead, it operates through subtle signals, uncomfortable questions, and boundary violations framed as compliments. Dean Armitage’s insistence that he would have voted for Obama sounds like allyship but functions as defensive credential-flaunting. It reduces Obama to a shield against accusations of racism. It makes Chris responsible for absolving Dean’s potential bias. The seemingly innocent comment carries complex power dynamics in its subtext.

The phrase “Is it better?” when referring to Chris being Black operates similarly. The white characters treat Blackness as an exotic condition to be examined and discussed. They objectify Chris while maintaining polite smiles. The subtext reveals their inability to see him as simply human rather than fundamentally other. This casual dehumanization prepares audiences for the literal objectification that the plot will reveal.

Peele’s genius lies in making subtext text through the horror genre. The Armitage family’s polite racism literally masks their intention to steal Black bodies. The metaphor becomes reality. Every uncomfortable microaggression Chris experiences foreshadows the ultimate violation. The film works as social commentary and horror simultaneously because Peele understands that subtext about power, race, and objectification can be externalized through genre conventions while remaining psychologically true.

Table 7: Microaggressions as Subtext in Get Out

| Surface Interaction | Apparent Intent | Subtext Meaning | Horror Genre Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obama voting comment | Establishing progressive credentials | Defensive deflection using Black figure as shield | Foreshadows appropriation of Black identity |

| Questions about athletic ability | Expressing admiration | Reducing person to physical stereotypes | Prepares for literal body commodification |

| Touching hair without permission | Showing curiosity and interest | Violating bodily autonomy through entitlement | Previews ultimate violation of physical agency |

| Comments about strength and genetics | Offering compliments | Objectifying and dehumanizing through exoticization | Reveals eugenic thinking behind family’s plot |

Conclusion: Why Subtext Remains the Soul of Storytelling

Great stories live in the space between what is said and what is meant. From Casablanca’s nostalgic farewell to Get Out’s horror of objectification, subtext creates the emotional resonance that makes narratives unforgettable. The six examples explored here span decades and genres, yet they share a fundamental understanding of human psychology. People rarely say exactly what they mean. The gap between surface and depth creates the territory where meaningful storytelling happens.

Subtext works because it mirrors how we actually live. We navigate social situations through implication and code. We hide vulnerability behind casual conversation. We express love through gestures rather than declarations. Writers who master subtext tap into these universal human patterns. They create characters who feel authentic because they communicate like real people, with layers of meaning beneath their words.

The psychological power of subtext cannot be overstated. It transforms readers from passive consumers into active participants. When we decode hidden meaning, we invest ourselves in the story. We feel smart for catching implications. We feel connected to characters whose inner lives we’ve worked to understand. This active engagement creates memories that outlast plot details. We might forget what happened in a story, but we remember how subtext made us feel.

Different techniques create subtext across different forms. Hemingway’s Iceberg Theory advocates strategic omission. Freudian frameworks reveal how repression creates meaning beneath behavior. Genre conventions externalize psychological subtext into plot. Every writer must find approaches that suit their voice and story. The common thread remains commitment to layered meaning rather than surface simplicity.

Writers who embrace subtext move beyond competent storytelling into artistry. The difference between good writing and great writing often lives in what remains unspoken. Simple dialogue becomes charged with history. Casual gestures reveal hidden emotion. Silence speaks volumes. Mastering subtext requires patience and restraint. It demands trusting readers to do interpretive work. It means resisting the urge to explain everything explicitly.

The examples here offer starting points for developing subtext in your own work. Study how repeated phrases accumulate meaning. Notice how tone and content create productive dissonance. Observe how silence and omission can carry more weight than exposition. Practice embedding meaning in ordinary conversation and simple actions. The more you work with subtext, the more naturally it flows into your storytelling.

Table 8: Key Subtext Techniques Across Examples

| Story Example | Primary Technique | Psychological Effect | Application for Writers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casablanca | Repeated phrase with shifting context | Accumulates emotional weight through pattern | Use simple language that gains meaning through repetition and circumstance |

| The Godfather | Euphemism and tonal dissonance | Creates menace through understated civility | Make characters reveal power through what they avoid saying directly |

| Lost in Translation | Strategic omission and silence | Generates active audience participation | Trust readers to interpret meaning from gesture and context |

| Pulp Fiction | Mundane conversation in extreme situation | Reveals character through tonal mismatch | Contrast dialogue content with situational gravity |

| Streetcar Named Desire | Physical metaphor for psychological state | Externalizes internal conflict | Use consistent symbols that embody character psychology |

| Get Out | Social subtext made literal through genre | Transforms metaphor into plot reality | Layer social commentary beneath genre conventions |

Subtext remains the soul of storytelling because it honors the complexity of human experience. We are never one thing. We always carry contradictions, secrets, and layers. Stories that acknowledge this complexity through subtext achieve depth that straightforward narratives cannot match. The challenge for every writer is finding the courage to leave things unsaid, trusting that the silence will speak.

As you develop your own stories, ask yourself what your characters hide. What do they refuse to acknowledge? What gaps exist between their words and their feelings? What would they never say directly? These questions lead to the rich territory where subtext lives. The answers transform simple scenes into moments that resonate long after the story ends. Master subtext, and you master the psychology that makes storytelling unforgettable.