Table of Contents

Introduction: Tragedy and the Pulse of Real Stories

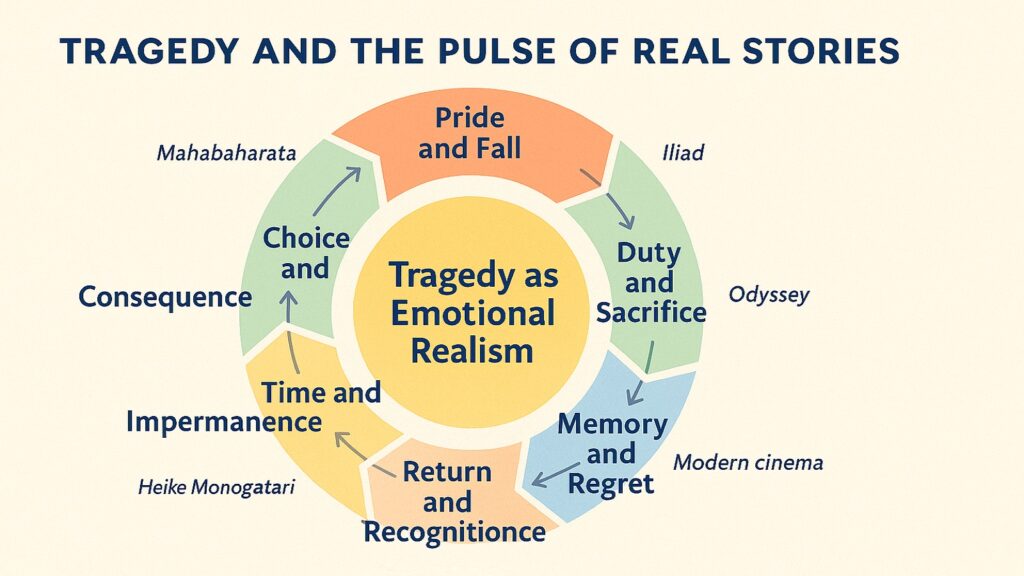

Tragedy is not about sadness. It is about truth. From the moral ruins scattered across the Mahabharata’s battlefield to the flawed heroes stumbling through modern cinema, tragedy exposes what makes us most human. It reveals the consequence that follows every choice, the weight that bends every noble intention, and the slow collapse that no amount of strength can prevent. Tragedy strips away the illusion that goodness guarantees safety or that power ensures permanence. What remains is emotional realism, the kind of storytelling that feels true because it mirrors the fragility we recognize in ourselves.

The ancient epics understood this. When Arjuna hesitates before battle, when Achilles chooses wrath over wisdom, when Rama upholds duty at the cost of his own happiness, these stories do not comfort us with easy victories. They show us the price of being alive. They remind us that every decision carries hidden doom, that pride invites collapse, and that memory does not fade but repeats until regret becomes its own prison. Modern storytelling has inherited this tradition. The craft has evolved, but the core remains unchanged. Tragedy still works because it forces audiences to witness the slow tightening of consequence, the quiet erosion of hope, and the painful recognition that some losses cannot be undone.

This article explores six aspects of tragedy that make stories feel real. Each section examines how myth and craft intertwine to create narratives that linger long after the final page. We begin with the tragedy of choice, where decisions shape destiny. We move through the tragedy of pride, where arrogance blinds even the greatest.

We examine the tragedy of duty, where virtue becomes a path to destruction. We explore the tragedy of memory, where the past haunts the present. We consider the tragedy of time, where everything built eventually crumbles. Finally, we confront the tragedy of return, where home is never what it was. Together, these elements reveal why tragedy endures as one of the most important story archetypes, a mirror that reflects our deepest truths.

Tragedy Compared with Other Story Archetypes

| Story Archetypes | Core Emotional Movement |

|---|---|

| Tragedy | Descent from stability to irreversible loss through consequence |

| Rags to Riches | Ascent from poverty or obscurity to prosperity and recognition |

| Quest For Meaning | Journey outward to discover purpose and return transformed |

| Voyage and Return | Departure into unfamiliar territory and safe return home |

| Overcoming The Monster | Confrontation with external threat leading to victory and restoration |

| Rebirth and Revelation | Transformation through suffering into renewed understanding or redemption |

1. Tragedy of Choice: When Decisions Shape Destiny

Tragedy often begins not with fate but with a choice. The moment Arjuna stands paralyzed on the battlefield in the Mahabharata, he faces a decision that will define everything. He sees his teachers, his cousins, his friends arrayed against him. Krishna urges him forward, but Arjuna hesitates. The choice is not between good and evil. It is between duty and love, between the rightness of war and the horror of killing those he cherishes. When he finally lifts his bow, the decision unleashes consequences that cannot be recalled. The battlefield will run red, and the victory will taste like ash.

Achilles in the Iliad makes a different choice, but the weight is the same. He chooses pride over peace, wrath over wisdom. He knows the prophecy. If he stays and fights, he will die young but earn eternal glory. If he leaves, he will live long but be forgotten. He chooses glory. He chooses rage. When Hector kills Patroclus, Achilles returns to battle not for honor but for vengeance. His choice leads to his own death, to the fall of Troy, to a cascade of suffering that spreads like poison through the story. The tragedy is not that fate forced his hand. The tragedy is that he chose this path knowing where it led.

Modern storytelling understands this dynamic. Foreshadowing and subtext hint that every decision carries hidden doom. A character’s choice to lie, to leave, to stay silent creates a moral tension that tightens with each scene. Audiences feel it. They sense the slow approach of consequence even when the characters cannot. This is what makes tragedy feel authentic.

We recognize the pattern because we have lived it. We have made choices that seemed right in the moment but unraveled into regret. We have watched others choose paths that led to their own destruction. Tragedy mirrors this truth. It shows that flawed choices make characters human, and that authenticity comes not from perfection but from the recognition that every decision is a gamble with invisible stakes.

The craft of storytelling amplifies this effect. Silence becomes as powerful as dialogue. A pause before an answer, a glance away, a hesitation before commitment all signal that the character senses the weight of the moment. The audience leans in. They understand that this choice matters, that the story will pivot here, that what comes next cannot be undone. This is the tragedy of choice. It is not about predestination. It is about freedom and the terrifying responsibility that comes with it. When tragedy works, it reminds us that we are the architects of our own downfall.

Tragedy of Choice in Classical and Modern Narratives

| Narrative Example | Tragedy and Choice Made and Its Consequence |

|---|---|

| Mahabharata (Arjuna) | Chooses duty over love, leading to victory shadowed by grief |

| Iliad (Achilles) | Chooses glory over long life, ensuring fame but inviting death |

| Oedipus Rex | Chooses to flee prophecy, unknowingly fulfilling it through that very flight |

| Hamlet | Chooses hesitation over action, prolonging suffering and multiplying deaths |

| Breaking Bad (Walter White) | Chooses pride over humility, transforming from teacher to monster |

| The Godfather (Michael Corleone) | Chooses family loyalty over innocence, losing his soul to power |

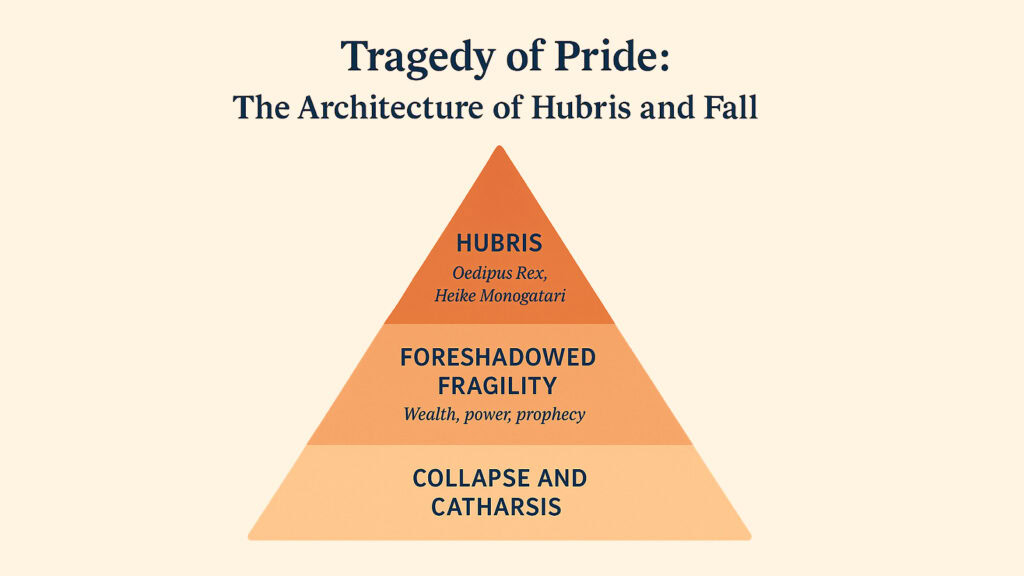

2. Tragedy of Pride: The Fall That Feels Deserved

Pride is the universal catalyst for collapse. The Heike Monogatari opens with a line that echoes through centuries: the proud do not endure. The sound of the Gion bell tolls for those who believe themselves invincible. The Japanese epic chronicles the rise and fall of the Taira clan, warriors who climbed so high they forgot the ground beneath them. Their arrogance invited rebellion. Their certainty blinded them to danger. When they fell, the fall felt not like injustice but like inevitability. The audience watches and understands. This is what happens when pride replaces humility, when power becomes its own justification.

Greek tragedy understood this pattern long before. Oedipus Rex stands as the archetype of hubris. Oedipus believes he can outrun prophecy through intelligence and will. He solves the riddle of the Sphinx. He becomes king. He rules with confidence and strength. But his pride blinds him to the truth unfolding before his eyes. When the revelation comes, when he realizes that every action taken to escape his fate has brought him closer to it, the collapse is total. He tears out his own eyes. The physical blindness mirrors the spiritual blindness that pride imposed all along. The tragedy feels deserved not because Oedipus is evil but because his arrogance made him refuse to see.

Foreshadowing and symbolic worldbuilding amplify this effect. The storyteller builds the height from which the character will fall. Palaces gleam with gold. Crowns rest heavy on confident brows. Armies march in perfect formation. The audience sees the symbols of power and understands that they are also markers of doom. The higher the climb, the harder the fall. This emotional contrast between invincibility and fragility is where tragedy lives. When the proud character stands at the peak, surveying their domain with satisfaction, the audience already feels the approach of collapse. The tragedy is not in the fall itself but in the recognition that pride made it inevitable.

Modern storytelling continues this tradition. Characters who believe themselves untouchable invite disaster. Corporate executives who ignore warning signs, political leaders who silence dissent, heroes who believe their strength makes them immune to consequence all follow the same arc. The craft of tragedy requires that the audience see the pride clearly even when the character cannot. This creates dramatic irony. We watch knowing what the character refuses to acknowledge. When the fall comes, it feels both shocking and expected. That paradox is the heart of tragedy. We know it is coming, but the impact still breaks something inside us.

Tragedy of Pride Across Cultures

| Cultural Example | Tragedy Throught Manifestation of Pride and Downfall |

|---|---|

| Heike Monogatari (Taira clan) | Military dominance breeds arrogance, leading to clan annihilation |

| Oedipus Rex | Intellectual pride blinds king to truth, resulting in self-mutilation |

| Macbeth | Ambition distorts judgment, transforming hero into tyrant and corpse |

| Ramayana (Ravana) | Demonic king’s pride in power leads to war and death |

| The Great Gatsby | Social climbing and obsession with image end in murder and isolation |

| Game of Thrones (Cersei) | Political arrogance ignores consequences, culminating in total destruction |

3. Tragedy of Duty: The Noble Path That Destroys

Some tragedies arise not from vice but from virtue misapplied. Rama in the Ramayana embodies this paradox. He is the perfect king, the ideal son, the warrior who never falters in his commitment to dharma. Yet this very commitment leads to his deepest sorrow. He sends Sita into exile because duty demands it, even though his heart breaks. He sacrifices personal happiness for the sake of public righteousness. The tragedy is quiet. There are no dramatic deaths, no battlefield horrors. There is only the slow erosion of joy beneath the weight of noble intent. The audience watches Rama walk the path of duty and understands that virtue, when followed without mercy or flexibility, can destroy as surely as vice.

Antigone offers a parallel from Greek tradition. She chooses to honor her brother with burial rites even though the king has forbidden it. Her choice is not selfish. It is rooted in religious duty, in the belief that some laws stand higher than human decree. She knows the cost. She faces death willingly. But the tragedy extends beyond her sacrifice. Her death triggers a cascade of suffering. Her fiancé kills himself. His mother follows. The king who ordered her execution is left alone with his grief. Antigone’s commitment to honor becomes the instrument of widespread destruction. The tragedy feels real because it shows that doing right can still lead to ruin.

The storytelling tools that make this work include emotional arc and subtext. The audience senses the erosion happening beneath the surface. A character speaks of duty with conviction, but their eyes betray exhaustion. They smile, but the smile does not reach their heart. The narrative arc bends slowly downward even as the character insists they are doing what must be done. This restraint makes the tragedy more powerful. There are no explosive confrontations, no moments of dramatic reversal. There is only the quiet recognition that the noble path has led somewhere dark and inescapable.

Modern narratives explore this pattern through characters who sacrifice everything for a cause or a principle. Soldiers who follow orders that destroy their conscience. Parents who work themselves to death for children who grow distant. Leaders who make impossible choices in service of the greater good. These stories feel painfully real because they mirror the dilemmas we face. We understand that virtue can become its own trap, that following the noble path does not guarantee a happy ending. Tragedy reminds us that sometimes the right choice still leads to loss, and that understanding this does not make the loss any easier to bear.

Tragedy of Duty in Epic and Modern Storytelling

| Narrative Example | Duty Upheld and Personal Cost Paid |

|---|---|

| Ramayana (Rama) | Upholds dharma by exiling Sita, losing marital happiness |

| Antigone | Honors divine law through burial, facing execution |

| Bhagavad Gita (Arjuna) | Accepts warrior duty despite moral anguish over violence |

| A Man for All Seasons (Thomas More) | Refuses to compromise conscience, leading to beheading |

| The Dark Knight (Batman) | Takes blame for murders to protect hope, becoming outcast |

| Schindler’s List | Saves lives through moral duty, haunted by those not saved |

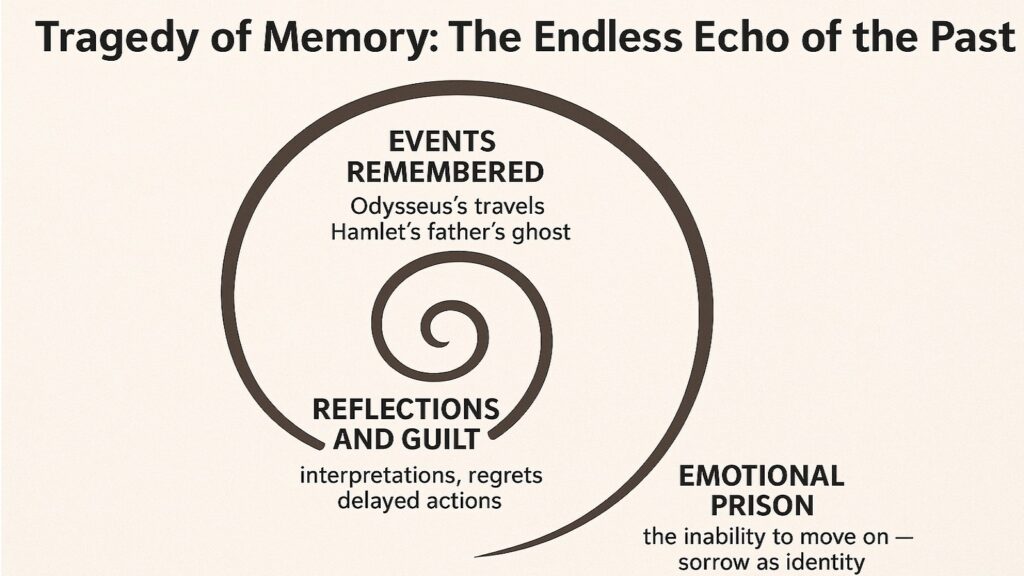

4. Tragedy of Memory: The Weight of What Cannot Be Undone

Memory in tragedy does not fade. It repeats, reframes, and reshapes until regret becomes its own form of imprisonment. Odysseus in the Odyssey spends years yearning for home. He survives monsters and gods, temptation and war. But the real tragedy is not the physical journey. It is the weight of memory that grows heavier with each passing season. He remembers Ithaca as it was, his wife as she was, his son as a child. When he finally returns, twenty years have passed. The home he remembers exists only in his mind. The memory has become both his anchor and his prison.

Hamlet offers another vision of this tragedy. He is paralyzed by remembrance. His father’s ghost demands vengeance, but Hamlet cannot act. He is trapped in the loop of memory, replaying his father’s death, questioning the ghost’s reality, doubting his own strength. The play within the play mirrors his paralysis. He stages his father’s murder to catch the king’s conscience, but in doing so he only deepens his own entrapment. Memory does not propel him toward resolution. It holds him suspended between past and future, unable to move forward because the past refuses to release him.

Storytellers use flashback and nonlinear narrative to make audiences relive these echoes of loss. A scene in the present triggers a memory from the past. The narrative jumps backward, showing what was lost, what was broken, what can never be repaired. The audience experiences the weight of memory as the character does. We understand that tragedy lingers not because the event is over but because memory keeps it alive. Every time the character remembers, the wound opens again. This is what makes tragedy feel real. It shows that time does not heal all wounds. Some wounds become permanent parts of who we are.

Modern cinema and literature continue to explore this dynamic. Characters haunted by war, by lost love, by mistakes they cannot undo. The past intrudes into the present through dreams, through involuntary memories, through moments that echo what was. The craft of tragedy requires that these memories feel specific and vivid. A smell that recalls a lost home. A song that brings back a dead lover. A photograph that captures a moment before everything fell apart. These details make the tragedy concrete. They show that memory is not abstract nostalgia but a lived experience that shapes every moment of the present.

Tragedy of Memory in Classical and Contemporary Works

| Narrative Example | Memory’s Role in Sustaining Tragedy |

|---|---|

| Odyssey (Odysseus) | Yearning for home sustained over decades, return reveals irreversible change |

| Hamlet | Father’s death paralyzes present action through obsessive remembrance |

| Aeneid (Aeneas) | Troy’s destruction haunts journey, past loss shadows future founding |

| Beloved (Toni Morrison) | Slavery’s trauma returns as ghost, memory refusing to stay buried |

| Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind | Attempts to erase painful memories reveal their essential role |

| Arrival | Knowledge of daughter’s death shapes every moment of life |

5. Tragedy of Time: The Slow Collapse of Everything Built

Nothing lasts. The Heike Monogatari opens with the sound of the Gion bell echoing across the centuries. The bell tolls for impermanence, for the Buddhist truth that all glory fades. The Taira clan rose to unimaginable power, but their dominance lasted barely a generation. This epic chronicles not just their political fall but the slow disintegration of everything they built. Fortresses crumble. Alliances dissolve. Warriors who once seemed invincible die in obscurity. The tragedy is not sudden. It is the gradual erosion that no amount of strength can prevent.

This pattern appears across cultures and centuries. Civilizations rise with confidence and optimism. They build monuments meant to last forever. They establish systems they believe are unshakeable. But time erodes everything. Worldbuilding in modern fiction mirrors this ancient insight. Cities decay. Relationships fracture under the pressure of years. Ideals that once seemed absolute become compromised, then forgotten. The craft of tragedy uses foreshadowing and suspense to show this erosion in progress. A crack in a wall. A moment of doubt in a relationship. A law that is bent once, then again, until it no longer holds any weight.

The tone of this tragedy should feel like slow disintegration. There is a strange beauty in watching something collapse gradually. The ruins of a great empire can be more moving than the empire at its height because they remind us that nothing escapes time. Storytellers who understand this create narratives that feel elegiac. Characters fight to preserve what they love, but the audience knows the fight is already lost. The suspense is not whether the collapse will come, but how the characters will face it when it does.

Modern narratives explore this through stories of aging, of obsolescence, of traditions that lose relevance. A family business that thrives for generations then fails in a changing economy. A relationship that withstands years of hardship but cannot survive the slow accumulation of small resentments. A political system that functions until it suddenly does not. These stories feel true because they mirror what we see around us. Everything we build will eventually fall. Tragedy does not flinch from this truth. It holds the mirror steady and asks us to look.

Tragedy of Time Across Narrative Traditions

| Narrative Example | Manifestation of Impermanence and Decay |

|---|---|

| Heike Monogatari | Clan dominance dissolves within a generation through war |

| Ozymandias (Shelley poem) | Shattered statue in desert mocks king’s claim to eternal power |

| One Hundred Years of Solitude | Family saga ends in apocalyptic dissolution across generations |

| Norse Ragnarok myths | Gods and world destined for destruction despite their power |

| The Wire | Institutions decay as corruption and indifference erode reform |

| There Will Be Blood | Oil empire built through ruthlessness ends in isolation |

6. Tragedy of Return: When Home Is Not What It Was

Some tragedies end not in death but in recognition. Odysseus finally reaches Ithaca after twenty years of wandering. He defeats the suitors. He reclaims his throne. But the home he returns to is not the home he left. His son is a stranger. His wife has aged. The island has changed. More than that, Odysseus himself has changed. He has become someone who cannot fully return to what he was. The recognition that home is not what it was, that return is not redemption, becomes its own form of loss.

The Mahabharata ends similarly. The war is won. The Pandavas rule. But the cost has been total. Almost everyone they loved is dead. The kingdom they fought for feels empty. Yudhishthira walks away from the throne eventually, recognizing that victory has brought only sorrow. The tragedy is not in the war but in the aftermath, in the slow realization that what was fought for no longer holds meaning. The return to power is not a return to joy.

Modern storytelling uses techniques like in medias res and narrative hook to pull readers into a world already broken. The Godfather begins with Michael Corleone as an outsider to his family’s criminal empire. By the end, he has become the godfather himself. He has returned to the family, but in doing so he has lost his innocence, his soul, his wife’s trust. The return is complete, but it is not redemptive. It is tragic. The audience understands that sometimes coming home means losing yourself.

The craft of tragedy requires showing this recognition clearly. A character walks through familiar streets but sees them differently. A reunion happens but without joy. The physical return is possible, but the emotional return is not. This creates a particular kind of heartbreak. The character has survived, has overcome obstacles, has reached the destination. But the destination is no longer what they hoped it would be. Tragedy teaches that return is an illusion, that innocence once lost cannot be reclaimed, that understanding this is both necessary and unbearable.

Tragedy of Return in Epic and Modern Cinema

| Narrative Example | Nature of Return and Its Tragic Recognition |

|---|---|

| Odyssey (Odysseus) | Physical return to Ithaca reveals emotional distance from past self |

| Mahabharata (Pandavas) | Victory in war yields kingdom emptied of joy and meaning |

| The Aeneid (Aeneas) | Founding of Rome requires abandoning beloved Dido and Trojan past |

| The Godfather (Michael) | Return to family transforms innocent son into ruthless patriarch |

| The Deer Hunter | Return from Vietnam reveals unbridgeable gap between past and present |

| No Country for Old Men | Sheriff retires recognizing world has changed beyond comprehension |

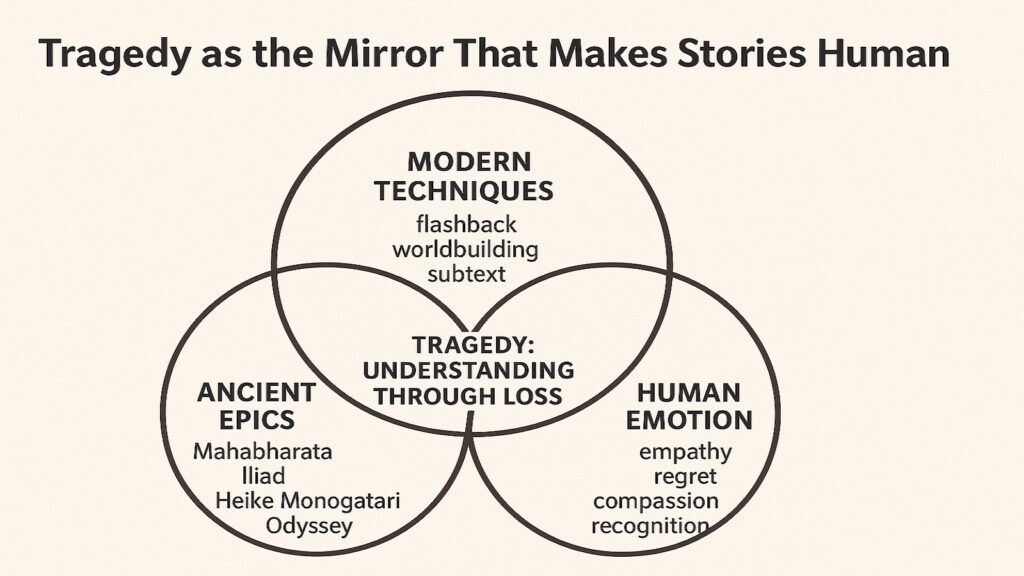

Conclusion: Tragedy as the Mirror That Makes Stories Human

Tragedy is not about despair. It is about understanding. When Arjuna lifts his bow, when Achilles returns to battle, when Rama sends Sita away, when Odysseus finally reaches home, these moments teach us something essential about what it means to be human. Tragedy shows that loss has meaning, that downfall reveals character, that even collapse can be beautiful if faced with honesty. The ancient epics understood this. They presented fate as divine, inescapable, woven into the fabric of existence itself. Modern stories have inherited this wisdom but transformed it. Today fate is psychological, rooted in choice and consequence rather than predetermined by gods. Yet the core remains unchanged.

Tragedy endures because it mirrors our deepest truth. We all make choices we cannot undo. We all carry pride that blinds us until it is too late. We all follow duties that cost more than we imagined. We all live with memories that will not fade. We all watch time erode what we built. We all discover that return is never simple. These are not abstractions. These are the experiences that define us. When we encounter them in stories, we recognize ourselves. That recognition is what makes tragedy feel real.

The craft matters. Foreshadowing creates the sense of approaching doom. Subtext reveals what characters cannot say. Emotional arc shows the slow descent from hope to recognition. Worldbuilding establishes what will be lost. Narrative structure controls when revelations hit hardest. But beneath all the craft is something simpler. Tragedy works because it refuses to lie. It does not promise that good people win or that hard work guarantees success. It does not suggest that love conquers all or that justice always prevails. Instead, it shows what happens when good people make terrible choices, when hard work leads to ruin, when love is not enough, when justice fails.

This honesty is what makes tragedy one of the most important story archetypes. It teaches empathy by forcing us to witness suffering without flinching. It reminds us that every story of loss is ultimately a story of what we dared to value. When tragedy is done well, when it shows consequence without melodrama and collapse without sentimentality, it becomes something close to sacred. It becomes a mirror that reflects not just characters on a page but ourselves, stripped of illusion, standing in the ruins of what we thought would last forever, still searching for meaning in the wreckage.

Tragedy’s Enduring Elements in Human Storytelling

| Tragic Element | Why It Resonates with Audiences |

|---|---|

| Inevitable consequence | Mirrors reality that actions have inescapable results |

| Flawed protagonists | Reflects our own imperfections and moral complexity |

| Recognition and reversal | Shows moment of understanding that comes too late |

| Emotional authenticity | Refuses comfort, demanding engagement with real pain |

| Universal themes | Explores pride, duty, memory, time that all humans face |

| Cathartic experience | Allows safe encounter with loss, preparing us for real grief |