Table of Contents

Universe Introduction: Setting the Stage for a Remarkable Odyssey

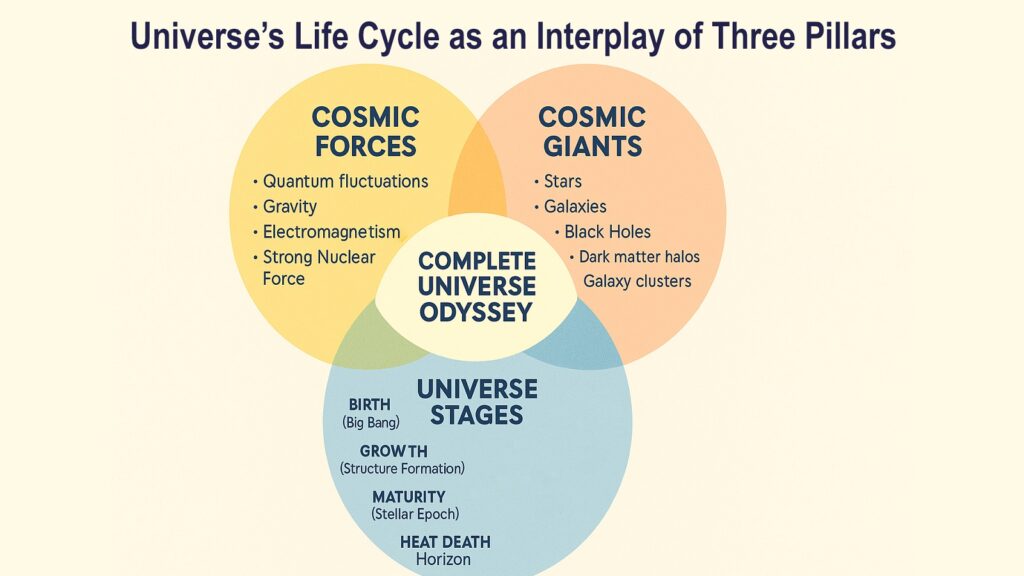

The Universe we inhabit is not a static backdrop but a living, breathing system that has evolved across billions of years. From its violent birth to its eventual quiet end, the Universe follows a path shaped by forces we can measure and giants we can observe. This cosmic drama unfolds through the interplay of fundamental forces and massive structures that together write the story of existence itself.

Cosmic forces include the quantum fluctuations that sparked creation, the inflationary expansion that stretched space, gravity that pulls matter together, and the four fundamental forces that govern all interactions. These invisible hands molded the Universe from its earliest moments. Meanwhile, cosmic giants emerged as the visible players in this drama: stars that forge elements, galaxies that house billions of suns, black holes that warp space and time, and dark matter that provides the scaffolding for everything we see.

The Universe has its own life cycle, much like any living system. It was born in a flash of energy. It grew through periods of rapid expansion and steady accumulation. It transformed as new structures emerged and old ones faded. Now it ages as dark energy pulls it apart, and eventually it will drift into a state of maximum disorder and minimum usable energy. This heat death represents not an explosion but a whimper, a slow fade into uniform darkness.

Understanding this journey requires seeing how cosmic forces and cosmic giants work together at every stage. Forces without giants would be mere mathematical abstractions. Giants without forces would have no means to form or evolve. Together they create the Universe we observe, a place where quantum mechanics meets galactic clusters, where microscopic particles shape the fate of structures spanning millions of light-years.

Overview of Cosmic Forces and Cosmic Giants

| Cosmic Element | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Quantum Fluctuations | Tiny energy variations that seeded all structure in the early Universe |

| Inflation | Exponential expansion that smoothed space while preserving density variations |

| Gravity | Attractive force that assembles matter into stars, galaxies, and clusters |

| Fundamental Forces | Electromagnetic, strong nuclear, weak nuclear, and gravitational interactions |

| Stars | Nuclear furnaces that create heavy elements through fusion reactions |

| Galaxies | Collections of billions of stars held together by gravity and dark matter |

| Black Holes | Regions where gravity becomes so intense that nothing can escape |

| Dark Matter | Invisible matter providing the gravitational framework for visible structures |

1. Universe Stage One: The Big Bang and the Primordial Quantum Spark

The Universe began approximately 13.7 billion years ago in a state of unimaginable density and temperature. This moment, known as the Big Bang, was not an explosion in space but an expansion of space itself. Everything that exists now was compressed into a volume smaller than a single atom, a singularity where our current laws of physics break down completely.

In the first fraction of a second, quantum fluctuations danced across this tiny realm. These fluctuations were not random noise but the seeds of every galaxy and star that would later form. As the Universe expanded, these microscopic variations in energy density were stretched and amplified, creating the blueprint for all future structure. Without these early quantum ripples, the Universe would have remained perfectly smooth, unable to form any of the cosmic giants we observe today.

During this primordial phase, the four fundamental forces separated from a unified state. Initially, all forces were one, but as the Universe cooled, symmetry broke, and they split into distinct interactions. First, gravity separated, then the strong nuclear force, and finally the electromagnetic and weak nuclear forces diverged. This symmetry breaking determined how particles would interact for the rest of cosmic history.

The temperature during these first moments exceeded trillions of degrees. Particles and antiparticles are constantly created and annihilated each other in a roiling soup of energy. A slight imbalance between matter and antimatter meant that when the annihilation ended, some matter remained. This leftover matter would become everything we see: every planet, every star, every living thing.

The forces unleashed during the Big Bang set the stage for cosmic giants to emerge. Gravity would pull matter together into clumps. The strong nuclear force would bind protons and neutrons into atomic nuclei. The electromagnetic force would hold electrons around nuclei, forming atoms. And the weak nuclear force would govern radioactive decay and certain stellar processes. Each force played its role in building the Universe we know.

Key Events in the Big Bang Era

| Event | Significance |

|---|---|

| Singularity | All matter and energy compressed into an infinitely small point |

| Quantum Fluctuations | Microscopic variations that seeded all cosmic structure |

| Symmetry Breaking | Separation of unified force into four distinct fundamental forces |

| Particle Creation | Formation of quarks, leptons, and force-carrying particles |

| Matter-Antimatter Imbalance | Slight excess of matter over antimatter allowed Universe to persist |

| First Protons and Neutrons | Quarks combined to form the building blocks of atomic nuclei |

| Temperature Extremes | Conditions exceeding trillions of degrees in the first microseconds |

| Spacetime Emergence | The fabric of reality itself began expanding from a point |

2. Universe Stage Two: Inflation and the First Architecture of Space-Time

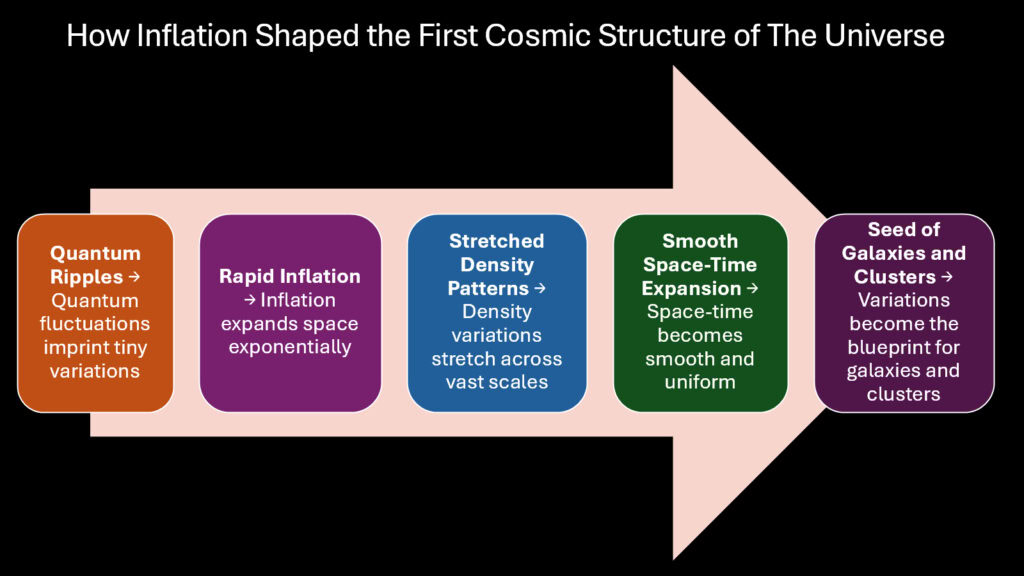

Within the first fraction of a second after the Big Bang, the Universe underwent a period of exponential expansion known as inflation. During this brief moment, space grew by a factor of at least 1026, increasing from subatomic to macroscopic scales in less time than it takes light to cross an atom. This violent stretching solved several puzzles about why the Universe appears so uniform yet contains the variations needed for structure.

Inflation smoothed out most irregularities in the early Universe, explaining why regions separated by vast distances have nearly identical properties today. These regions could never have exchanged information at light speed, yet they share the same temperature and density. Inflation solves this by having them start from a tiny connected region that was then stretched apart faster than light could travel between the emerging sections.

Yet inflation did not smooth everything perfectly. The quantum fluctuations from the Big Bang era were also stretched during this expansion. What started as microscopic energy variations became cosmic-scale density differences. These stretched fluctuations created slightly denser and less dense regions across space. Gravity would later amplify these small differences, turning them into galaxies, galaxy clusters, and the vast cosmic web we observe today.

The patterns created during inflation determined where cosmic giants would eventually form. Denser regions attracted more matter through gravity, while less dense regions became voids. The cosmic web emerged from this blueprint: long filaments of galaxies connected by thin bridges, surrounding enormous empty spaces. Superclusters containing thousands of galaxies formed where multiple filaments intersected, while voids hundreds of millions of light-years across remained nearly empty.

Space-time itself took on its large-scale geometry during inflation. The Universe became remarkably flat, meaning parallel lines remain parallel across cosmic distances rather than converging or diverging. This flatness requires an incredibly precise balance of matter, energy, and expansion rate. Even a tiny deviation would have created a Universe that collapsed back on itself or expanded so fast that no structures could form.

The inflationary period ended as suddenly as it began, transitioning into a slower expansion driven by radiation and matter. The energy that powered inflation converted into a hot soup of particles that filled the newly enlarged space. From this point forward, the Universe would cool and expand at a more measured pace, allowing the processes that create stars and galaxies to unfold over billions of years.

Characteristics of the Inflationary Epoch

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Duration | Approximately 10-35 seconds |

| Expansion Rate | Space grew by a factor exceeding 1026 |

| Quantum Stretching | Microscopic fluctuations expanded to cosmic scales |

| Horizon Problem Solution | Previously connected regions stretched beyond communication distance |

| Flatness | Universe geometry became nearly perfectly Euclidean |

| Density Variations | Tiny differences in matter distribution seeded future structure |

| Energy Conversion | Inflaton field energy transformed into matter and radiation |

| Cosmic Web Blueprint | Large-scale patterns determined where galaxies would later form |

3. Universe Stage Three: The Birth of Light and the First Atoms

After inflation ended, the Universe continued expanding and cooling for several hundred thousand years. During this time, the cosmos was opaque, filled with a hot plasma where electrons and photons constantly interacted. Light could not travel freely because photons scattered off the free electrons in every direction, trapped in an endless game of collision and redirection.

Around three hundred eighty thousand years after the Big Bang, the Universe cooled enough for a crucial transition called recombination. Electrons combined with protons to form neutral hydrogen atoms, with a smaller amount of helium also forming. This process removed most free electrons from space, allowing photons to travel unimpeded for the first time. The Universe became transparent, and light began its journey across cosmic distances.

The light released during recombination still fills the Universe today as the cosmic microwave background radiation. Originally visible and ultraviolet, this light has been stretched by the expansion of space into microwave wavelengths. Astronomers can detect it coming from every direction in the sky, a faint afterglow from when the Universe was less than one percent of its current age. The tiny temperature variations in this background radiation map the density differences that would grow into galaxies.

Dark matter played a crucial role during this era, even though it does not interact with light. Dark matter had already begun clumping under its own gravity, forming invisible halos that would later attract ordinary matter. These dark matter structures provided the gravitational wells where gas could collect and cool. Without dark matter, the ordinary matter we observe would not have had enough gravity to overcome the expansion of space and form the first stars.

Gravity worked patiently during this period, amplifying the small density variations inherited from inflation. Regions that started even slightly denser attracted more matter, becoming denser still. This process of gravitational collapse accelerated over time, creating a hierarchy of structures. Small clumps merged into larger ones, which merged into still larger formations, building up the cosmic architecture from the bottom up.

The atomic matter created during recombination was almost entirely hydrogen and helium, with trace amounts of lithium and beryllium. No heavy elements existed yet because those require the intense temperatures and pressures found inside stars. The Universe at this stage was chemically simple, lacking the carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and iron that would later prove essential for planets and life. Stars would need to ignite and die before the periodic table could be filled out.

Key Developments in the Era of Recombination

| Process | Impact on Universe Evolution |

|---|---|

| Plasma Era | Electrons and photons constantly interacted, making space opaque |

| Cooling Threshold | Temperature dropped below three thousand degrees Kelvin |

| Neutral Atom Formation | Electrons and protons combined into hydrogen and helium atoms |

| Photon Decoupling | Light traveled freely for the first time in cosmic history |

| Cosmic Microwave Background | Primordial light stretched into microwave radiation we detect today |

| Dark Matter Halos | Invisible structures began concentrating under gravity |

| Gravitational Amplification | Density variations grew through matter accumulation |

| Chemical Simplicity | Only lightest elements existed before stellar nucleosynthesis began |

4. Universe Stage Four: The Rise of Stars and the First Cosmic Giants

Within the dark matter halos scattered across the Universe, clouds of hydrogen and helium gas began to collapse under gravity. As these clouds contracted, their centers grew hotter and denser. Eventually, the temperature and pressure reached levels where nuclear fusion could ignite. The first stars blazed to life roughly one hundred to two hundred million years after the Big Bang, ending the cosmic dark ages and beginning the era of cosmic giants.

These earliest stars differed dramatically from the Sun and other modern stars. Composed almost entirely of hydrogen and helium, they lacked the heavier elements that help regulate temperature in contemporary stars. As a result, many first-generation stars grew to enormous masses, perhaps one hundred or even several hundred times the mass of the Sun. They burned ferociously hot and died quickly, living only a few million years before exploding as supernovae.

Nuclear fusion in stellar cores converts lighter elements into heavier ones through a process that releases tremendous energy. Inside stars, hydrogen fuses into helium, releasing the energy that makes stars shine. In more massive stars, helium fuses into carbon and oxygen. Even heavier stars can create neon, magnesium, silicon, and eventually iron through successive fusion stages. Each step requires higher temperatures and pressures than the last.

When massive stars exploded as supernovae, they scattered these newly created elements across space. The shockwaves from these explosions compressed nearby gas clouds, triggering new rounds of star formation. Each generation of stars incorporated some of the heavy elements from previous generations, gradually enriching the cosmic chemical inventory. After billions of years of stellar cycling, space contained enough carbon, oxygen, silicon, and iron to build rocky planets like Earth.

Stellar radiation also transformed the Universe in fundamental ways. Ultraviolet light from the first stars reionized the hydrogen atoms that had formed during recombination, stripping electrons away once more. This reionization created bubbles of ionized gas around each star and galaxy, which gradually merged as more stars ignited. By about one billion years after the Big Bang, the entire Universe had been reionized, returning to a state where free electrons could interact with photons.

The life cycles of stars became a cosmic recycling system. Stars form from collapsing gas clouds, shine for millions or billions of years through fusion, then return much of their material to space through stellar winds or explosive deaths. This material mixes with pristine hydrogen and helium to seed new star formation. The cycle continues, with each iteration creating a more chemically complex Universe capable of supporting planets and eventually life.

Stellar Evolution and Nucleosynthesis

| Stellar Process | Cosmic Consequence |

|---|---|

| Gravitational Collapse | Gas clouds contracted until fusion ignited in their cores |

| Hydrogen Fusion | Primary energy source converting mass into light and heat |

| Helium Burning | Creation of carbon and oxygen in stellar cores |

| Heavy Element Production | Successive fusion stages built elements up to iron |

| Supernova Explosions | Scattered newly forged elements across interstellar space |

| Reionization | Stellar ultraviolet light stripped electrons from hydrogen atoms |

| Chemical Enrichment | Each stellar generation increased heavy element abundance |

| Cosmic Recycling | Material cycled between stars and interstellar medium |

5. Universe Stage Five: Galaxies, Black Holes, and the Growth of Structure

As stars began forming across the Universe, they did not appear randomly but gathered into larger structures called galaxies. These galaxies formed along the scaffolding provided by dark matter, which outweighs ordinary matter by a factor of five to one. Dark matter’s gravity pulled ordinary matter into its invisible halos, where gas could cool and condense into stars. The result was a cosmic web of galaxies connected by filaments and separated by voids.

The first galaxies were small by modern standards, containing perhaps millions of stars rather than the hundreds of billions found in large galaxies today. These early galaxies collided and merged frequently, growing larger through cosmic cannibalism. When galaxies merge, their stars rarely collide directly because the distances between stars are so vast. Instead, the galaxies’ shapes distort, their gas clouds compress and trigger new star formation, and their central black holes eventually combine.

At the centers of most large galaxies lurk supermassive black holes containing millions or billions of solar masses. These objects grew through two main processes: accretion of surrounding matter and mergers with other black holes. When matter falls toward a black hole, it forms a swirling disk that heats up to millions of degrees, emitting intense radiation. This active galactic nucleus can outshine all the stars in the galaxy combined, visible across billions of light-years.

Galaxy clusters represent the largest gravitationally bound structures in the Universe. They contain hundreds or thousands of individual galaxies held together by their mutual gravitational attraction and embedded in dark matter halos. Between the galaxies flows hot gas at temperatures of tens of millions of degrees, emitting X-rays as it collides with itself. This intracluster medium contains more ordinary matter than all the stars in all the galaxies combined.

On even larger scales, galaxy clusters group into superclusters, though these structures are not gravitationally bound. They represent the statistical clustering of matter along the densest filaments of the cosmic web. The Milky Way belongs to the Local Group of galaxies, which forms part of the Virgo Supercluster, which in turn belongs to the even larger Laniakea Supercluster spanning half a billion light-years.

The growth of structure follows a bottom-up pattern where small objects form first and merge into larger ones over time. This hierarchical assembly means the Universe becomes more structured and complex as it ages. Dwarf galaxies merge to form spiral and elliptical galaxies. These merge to form galaxy groups and clusters. The cosmic web becomes more pronounced as matter flows from voids into filaments and from filaments into clusters.

Angular momentum plays a crucial role in shaping galaxies. As a collapsing gas cloud rotates, conservation of angular momentum causes it to spin faster as it contracts. This rotation prevents the cloud from collapsing into a single point. Instead, it forms a rotating disk where stars form in spiral patterns. Elliptical galaxies form when galaxies merge and their orderly rotation gets scrambled into random stellar motions.

Structure Formation in the Cosmic Web

| Structure Type | Key Properties |

|---|---|

| Dark Matter Halos | Invisible gravitational wells that concentrate ordinary matter |

| Dwarf Galaxies | Early small galaxies containing millions of stars |

| Spiral Galaxies | Rotating disk galaxies with ongoing star formation |

| Elliptical Galaxies | Non-rotating galaxies formed through mergers |

| Supermassive Black Holes | Central engines containing millions to billions of solar masses |

| Galaxy Clusters | Groups of hundreds to thousands of galaxies bound by gravity |

| Intracluster Medium | Hot gas filling space between galaxies in clusters |

| Cosmic Web Filaments | Chains of galaxies connecting dense nodes across space |

6. Universe Stage Six: Dark Energy and the Accelerating Expansion

For billions of years after the Big Bang, gravity worked to slow the expansion of the Universe. The mutual gravitational attraction between all matter and energy acted as a brake, though it could not stop the expansion entirely. Astronomers expected to measure how much this deceleration had occurred by observing distant supernovae. Instead, in the late 1990s, they discovered something completely unexpected.

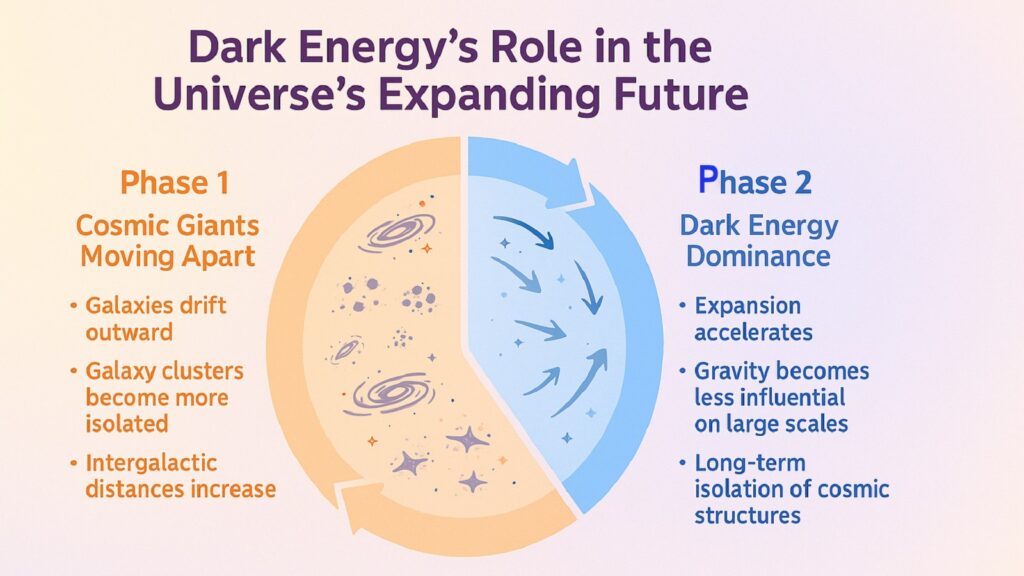

The Universe is not just expanding but accelerating. Distant galaxies are moving away from us faster than they were in the past, and the expansion rate continues to increase over time. This acceleration requires a repulsive force that overwhelms gravity on cosmic scales. Physicists call this mysterious component dark energy, and it now dominates the Universe’s energy budget, accounting for roughly sixty-eight percent of everything that exists.

The nature of dark energy remains one of the deepest puzzles in physics. The leading explanation treats it as a cosmological constant, an intrinsic energy density of empty space itself. This vacuum energy does not dilute as the Universe expands because new space comes with its own allocation of dark energy. As the Universe grows larger, the total amount of dark energy increases, while the density of matter decreases through dilution.

Dark energy began dominating the Universe’s evolution roughly six billion years ago, about the same time the Sun and Earth formed. Before this transition, matter density was high enough that gravity controlled cosmic dynamics, allowing structures to form and grow. After dark energy took over, the accelerating expansion began pulling unbound structures apart, limiting further growth of the cosmic web.

This acceleration fundamentally changes the long-term fate of cosmic giants. Galaxy clusters that are gravitationally bound will remain together, but clusters not bound to each other will separate forever. The Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies will still collide and merge because they are gravitationally bound, but most other galaxies will gradually recede beyond our ability to observe them as space expands faster between us.

The cosmic horizon represents the maximum distance from which light can reach us, given the Universe’s age and expansion rate. As dark energy accelerates the expansion, this horizon will eventually stop growing and even shrink in terms of the physical structures we can observe. Galaxies beyond a certain distance are moving away so fast that their light will never reach us, no matter how long we wait. Future astronomers, billions of years from now, will observe a lonelier cosmos with fewer visible galaxies.

Dark energy’s dominance marks a phase transition in cosmic evolution, from an era of growth and complexity to an era of dissipation and isolation. While gravity built up structures over the first nine billion years, dark energy will spend the rest of cosmic history tearing those structures apart. This represents a fundamental shift in the balance between cosmic forces, with profound implications for the Universe’s ultimate fate.

Dark Energy and The Cosmic Acceleration

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Discovery Era | Observations of distant supernovae in 1998 |

| Energy Density | Comprises approximately sixty-eight percent of total cosmic content |

| Vacuum Energy | Possible explanation as intrinsic energy of empty space |

| Cosmological Constant | Mathematical representation of unchanging energy density |

| Acceleration Onset | Dark energy began dominating about six billion years ago |

| Expansion Rate | Currently increasing over time rather than decreasing |

| Structure Growth Limit | Prevents formation of new gravitationally bound clusters |

| Cosmic Horizon | Maximum observable distance will eventually shrink |

7. Universe Stage Seven: The Long Twilight of Stars and Galactic Decline

Looking into the deep future, the Universe will enter an era of gradual decline as star formation winds down. New stars form when gas clouds collapse under gravity, but the raw materials for this process are finite. Each generation of stars locks up some material in stellar remnants like white dwarfs, neutron stars, and black holes. Some gas escapes from galaxies into intergalactic space, where it becomes too diffuse to collapse. Over trillions of years, galaxies will exhaust their star-forming fuel.

The last stars to shine will be red dwarfs, the smallest and longest-lived members of the stellar family. These stars burn their hydrogen fuel so slowly that they can shine for trillions of years, far longer than the current age of the Universe. A red dwarf with a tenth of the Sun’s mass might live for ten trillion years, while the Sun itself will die after only ten billion years total. By the time the last red dwarfs flicker out, the Universe will be one hundred trillion years old.

As star formation ends, galaxies will grow dimmer with each passing billion years. The bright blue stars that illuminate spiral arms will die first, followed by yellow stars like the Sun, and eventually even the long-lived red dwarfs. Dead stars will outnumber living ones by vast margins. White dwarfs and neutron stars will cool gradually, radiating away their residual heat into space until they match the background temperature of the cosmos.

Black holes will continue to grow by consuming any matter that strays too close. In dense galactic centers, black holes may merge with each other, creating even more massive objects. But as galaxies empty of gas and stars spread out through stellar evolution and gravitational interactions, even black holes will run short of food. They will enter a quiet period of slow growth through occasional captures.

Galactic collisions will continue in gravitationally bound clusters, but the resulting merged galaxies will be dark, containing mostly stellar remnants rather than shining stars. These collisions will scramble stellar orbits, occasionally flinging stars out of galaxies entirely into intergalactic space. Over time, galaxies will dissolve partially through this evaporation process, while their cores become denser.

Brown dwarfs, objects too small to sustain hydrogen fusion, will cool from red to black, becoming invisible except through their gravitational effects. Planets will continue orbiting dead stars, frozen and dark. Any remaining atmospheres will snow out onto their surfaces. The Universe will become a dark, cold place where most matter is locked up in dead objects that emit little or no radiation.

The expansion of space continues throughout this era, accelerated by dark energy. Galaxies outside the Local Group will have receded beyond the cosmic horizon, disappearing from view. Observers in the far future will see a Universe containing only their own merged galaxy cluster, surrounded by darkness in every direction. The rich cosmic web visible today will be invisible to them, erased not by time but by expansion.

The Era of Stellar Decline

| Phenomenon | Timeline and Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Star Formation Cessation | Gas supplies exhausted over trillions of years |

| Red Dwarf Dominance | Smallest stars become only active sources of light |

| White Dwarf Cooling | Dead stellar cores radiate away residual heat |

| Black Hole Growth | Central massive objects continue growing through accretion |

| Galactic Evaporation | Stars ejected from galaxies through gravitational interactions |

| Brown Dwarf Cooling | Failed stars fade from red to complete darkness |

| Planetary Freezing | Worlds locked in orbit around dead stars cool to near absolute zero |

| Cosmic Horizon Shrinkage | Accelerating expansion removes distant galaxies from view |

8. Universe Stage Eight: The Final Drift Toward Heat Death

In the extremely distant future, perhaps 10100 years from now, the Universe will enter its final phase of evolution. The concept of heat death, also called the Big Freeze, describes a state where all usable energy has dissipated, and the Universe reaches maximum entropy. This represents equilibrium at the coldest possible temperature, with no energy gradients remaining to drive any processes.

White dwarfs and neutron stars will have cooled to the background temperature of space, becoming black dwarfs and black neutron stars, respectively. These objects will be nearly impossible to detect because they emit virtually no radiation. They will persist as cold, dark lumps of matter, gravitationally bound but thermally inert. If proton decay occurs, even these remnants will eventually dissolve into lighter particles and radiation.

The question of proton decay remains uncertain. Some theories of particle physics predict that protons should decay into lighter particles over timescales of 1034 years or longer. If this occurs, all atomic nuclei will eventually disintegrate, transforming matter into positrons, photons, and neutrinos. The last structures made of ordinary matter would vanish, leaving only black holes and diffuse radiation.

Black holes themselves are not eternal. Stephen Hawking showed that quantum effects near the event horizon cause black holes to emit radiation and slowly evaporate. The rate of this Hawking radiation is inversely proportional to the black hole’s mass, so larger black holes evaporate more slowly. A solar-mass black hole would take 1067 years to evaporate, while supermassive black holes might persist for 10100 years.

As black holes evaporate, they release their mass as radiation, returning it to the Universe in a final burst of energy. The largest black holes in the Universe will be the last structures to dissolve. When they finally evaporate, the Universe will contain nothing but an increasingly dilute sea of photons, neutrinos, and other particles, all stretched to longer and longer wavelengths by cosmic expansion.

Entropy increases throughout this process, moving the Universe toward a state of maximum disorder. Temperature differences vanish as hot objects cool and energy spreads uniformly across space. Without temperature gradients, no engines can operate, no work can be extracted, and no processes can run in any preferred direction. The arrow of time becomes meaningless in a universe at perfect equilibrium.

The final state represents the triumph of the second law of thermodynamics on cosmic scales. All the complexity built up over billions of years through the action of gravity, nuclear fusion, and structure formation will dissolve into featureless uniformity. The cosmic forces that shaped our cosmos will have completed their work, transforming a state of high energy density and low entropy into a state of low energy density and maximum entropy.

Ultimate Fate of Cosmic Structures

| Structure | Final State |

|---|---|

| White Dwarfs | Cool to black dwarfs at background temperature |

| Neutron Stars | Become black neutron stars emitting no detectable radiation |

| Proton Decay | Possible disintegration of atomic nuclei over immense timescales |

| Black Hole Evaporation | Hawking radiation causes gradual mass loss and eventual disappearance |

| Supermassive Black Holes | Last structures to evaporate after 10100 years |

| Photon Sea | Radiation stretched to infinite wavelengths by expansion |

| Entropy Maximum | Universe reaches state of complete thermal equilibrium |

| Heat Death | No usable energy remains to drive any processes |

Universe Conclusion: Reflecting on a Journey Across Deep Time

The Universe’s journey from the Big Bang to heat death spans an almost incomprehensible range of timescales, from the first fraction of a second to the unimaginable eons of the final era. Throughout this odyssey, the interplay between cosmic forces and cosmic giants shapes every transition, every structure, every moment of cosmic evolution. Forces provide the rules, and giants embody the results, together creating the rich tapestry we observe and study.

In the beginning, quantum fluctuations and inflation set the stage for everything that followed. These cosmic forces created the density variations that gravity would amplify into cosmic giants. The fundamental forces separated and defined how particles could interact, while the Big Bang’s expansion gave space itself room to evolve. From pure energy emerged matter, from matter emerged atoms, from atoms emerged stars.

Stars became the first true cosmic giants, transforming the Universe from a simple place of hydrogen and helium into a complex realm containing the full periodic table. Through nuclear fusion and supernova explosions, stars manufactured the elements needed for planets and life. They reionized space with their radiation and organized themselves into galaxies under gravity’s patient guidance.

Galaxies and black holes represent cosmic architecture at its grandest. The cosmic web spans billions of light-years, connecting galaxy clusters through filaments while isolating vast voids between them. Dark matter provides the invisible scaffolding for this structure, while dark energy works to tear it apart. The tension between gravity assembling and dark energy dispersing defines the Universe’s current era.

Looking forward, the Universe faces a long decline from complexity toward simplicity. Star formation will end, galaxies will darken, black holes will evaporate, and entropy will increase until nothing remains but cold, dispersed radiation. Yet even this dissolution follows from the same forces that created structure in the first place. Thermodynamics demands that energy spread out, and space’s expansion ensures that spreading continues forever.

This three-part journey through cosmic forces, cosmic giants, and the Universe’s stages reveals a unified story. Forces create conditions, giants emerge from those conditions, and together they evolve the Universe from one state to another. Each article in this trilogy illuminates a different aspect of the same cosmic narrative, showing how the fundamental rules of physics give rise to spectacular structures that eventually return to formless equilibrium.

The Universe’s story reminds us that complexity arises from simplicity and eventually returns to it. Between these two states of minimal structure lies the brief flourishing of stars, galaxies, planets, and perhaps consciousness itself. We exist in the middle chapters of a story that began with quantum foam and will end with diffuse radiation. Understanding this context helps us appreciate both the Universe’s grandeur and its transience.

The Universe Through Time

| Era | Defining Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Big Bang Birth | Quantum fluctuations and symmetry breaking created the seeds of structure |

| Inflationary Expansion | Exponential growth stretched tiny variations into cosmic-scale patterns |

| Atomic Formation | Electrons and nuclei combined, releasing light as the microwave background |

| Stellar Ignition | First stars forged heavy elements and reionized space |

| Galactic Assembly | Galaxies formed along dark matter scaffolding in the cosmic web |

| Dark Energy Dominance | Accelerating expansion began pulling unbound structures apart |

| Twilight Decline | Star formation ended and galaxies dimmed over trillions of years |

| Heat Death Approach | Black hole evaporation and entropy increase toward final equilibrium |