Table of Contents

Introduction: How the Hero’s Quest Redraws the Shape of Brokenness

The Hero’s Quest doesn’t begin with strength. It begins with a crack in the world that mirrors the crack in the hero’s soul. When Arjuna stands frozen on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, paralyzed by doubt and moral confusion, his story doesn’t start with courage—it starts with complete emotional collapse. This moment of brokenness isn’t the problem the Hero’s Quest will solve. It’s the very engine that drives every step forward.

Modern storytelling techniques have forgotten this truth. We’ve turned the Hero’s Quest into a formula for fixing people, a narrative assembly line that takes broken characters and spits out whole ones. But the greatest stories—from Homer’s wounded Achilles to the shattered Frodo carrying his burden through Middle-earth—understand something deeper. The Hero’s Quest is not solely focused on mending brokenness. Rather, it emphasizes the importance of learning to coexist with it..

Joseph Campbell’s concept of the monomyth provided the foundational structure for the Hero’s Quest, yet it overlooked the deeper emotional significance. The real power of these stories lies not in their ability to restore heroes but in their capacity to transform how we understand what it means to be broken. Each stage of the journey reveals another facet of emotional fracture, another way that wounds become windows.

Consider how differently we might read these stories if we stopped looking for triumph and started looking for truth. Odysseus doesn’t return home healed—he returns home haunted, forever changed by what he’s seen and done. His brokenness isn’t a bug in the narrative system; it’s a feature. The Hero’s Quest teaches us that some wounds are too sacred to heal, too meaningful to abandon.

This exploration will examine six ways the Hero’s Quest redefines our relationship with emotional brokenness. From Jungian shadows to post-structuralist fragments, from trauma’s spiral patterns to the eloquence of silence, we’ll discover how the greatest stories don’t fix us—they show us how to carry our cracks with grace.

Table 1: Core Elements of Brokenness in Classical Hero’s Quest Narratives

| Hero | Source of Brokenness | Expression in Quest | Transformation Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arjuna | Moral paralysis and duty conflict | Withdrawal from battle | Acceptance of paradox |

| Achilles | Rage and loss of Patroclus | Excessive violence and grief | Integration of mortality |

| Odysseus | Hubris and divine punishment | Extended wandering and suffering | Humility through endurance |

| Frodo | Burden of the Ring’s corruption | Physical and spiritual deterioration | Sacrifice without healing |

| Hamlet | Betrayal and existential doubt | Madness and delayed action | Embrace of uncertainty |

1. The Hero’s Quest as Archetypal Griefwork

Jung understood something about stories that most readers miss. The Hero’s Quest isn’t really about the hero at all—it’s about the collective unconscious working through its deepest wounds. When we follow Arjuna into his dark night of the soul on the battlefield, we’re not watching one man’s crisis. We’re witnessing humanity’s eternal struggle with duty, mortality, and the weight of choice.

The archetypal figures that populate every Hero’s Quest—the wise mentor, the threshold guardian, the shadow—aren’t random story elements. They’re emotional territories mapped by centuries of human grief. The mentor represents our hunger for wisdom in the face of loss. The threshold guardian embodies our resistance to change. The shadow holds everything we cannot bear to acknowledge about ourselves.

Jung called this shadow work, and it explains why the Hero’s Quest feels both foreign and familiar. When Achilles drags Hector’s body around Troy’s walls, he’s not just expressing personal rage—he’s channeling the archetypal fury of every person who has lost someone irreplaceable. The story gives form to formless grief, making the unbearable somehow bearable through symbol and metaphor.

This archetypal dimension explains why broken heroes resonate across cultures and centuries. Odysseus struggling with the trauma of war speaks to modern veterans returning from combat. Hamlet’s paralysis in the face of impossible choices echoes in anyone who has stood at a crossroads with no good options. The specific details change, but the emotional architecture remains constant.

The cave, a recurring motif in Hero’s Quest stories, signifies more than just physical peril. It’s the archetypal space where conscious and unconscious meet, where the hero must confront not external enemies but internal shadows. Frodo’s journey into Mordor mirrors every human being’s descent into their own darkness. The Ring he carries isn’t just a magical object—it’s the archetypal burden of consciousness itself.

What makes this archetypal griefwork so powerful is its refusal to promise healing. Jung knew that some wounds don’t heal—they integrate. The Hero’s Quest doesn’t fix the hero’s brokenness; it transforms the hero’s relationship with that brokenness. Arjuna does not emerge from the dialogue in the Bhagavad Gita free from his moral dilemmas. Instead, he gains a new perspective on how to bear them.

Table 2: Jungian Archetypes and Their Emotional Functions in Hero’s Quest

| Archetype | Emotional Function | Example from Literature | Type of Brokenness Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Shadow | Confronting rejected aspects of self | Gollum in Lord of the Rings | Self-hatred and moral compromise |

| The Mentor | Providing wisdom for grief processing | Lord Krishna to Arjuna | Paralysis from overwhelming choice |

| The Threshold Guardian | Representing resistance to change | Sphinx in Oedipus myth | Fear of unknown consequences |

| The Shapeshifter | Embodying uncertainty and betrayal | Iago to Othello | Trust issues and paranoia |

| The Herald | Announcing the call to transformation | Gandalf to Frodo | Resistance to responsibility |

2. Emotional Currencies of the Hero’s Quest

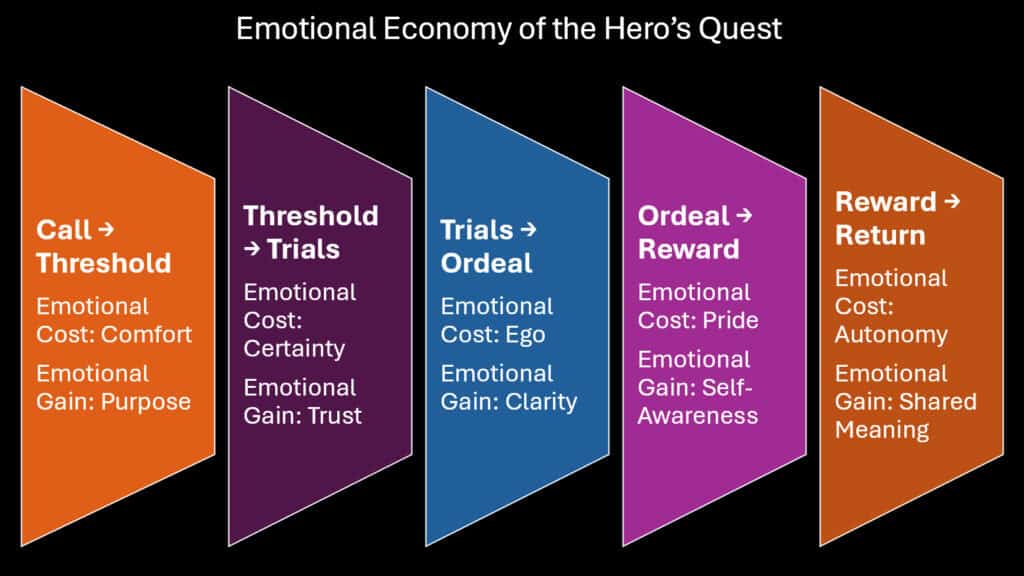

Every Hero’s Quest operates on an emotional economy that has nothing to do with gold or glory. The real currency is pain, and the exchange rate is brutal. Achilles pays for his moment of triumph over Hector with a lifetime of knowing he chose glory over longevity. Odysseus purchases each mile toward home with another piece of his innocence. The hero’s purse is always full of wounds.

This emotional currency system explains why physical action often feels hollow in Hero’s Quest narratives when it’s not backed by emotional weight. A sword fight without internal stakes is just choreography. But when that same sword fight represents a hero’s struggle with their own capacity for violence—as it does when Arjuna finally draws his bow at Kurukshetra—every blow carries the weight of a soul in conflict.

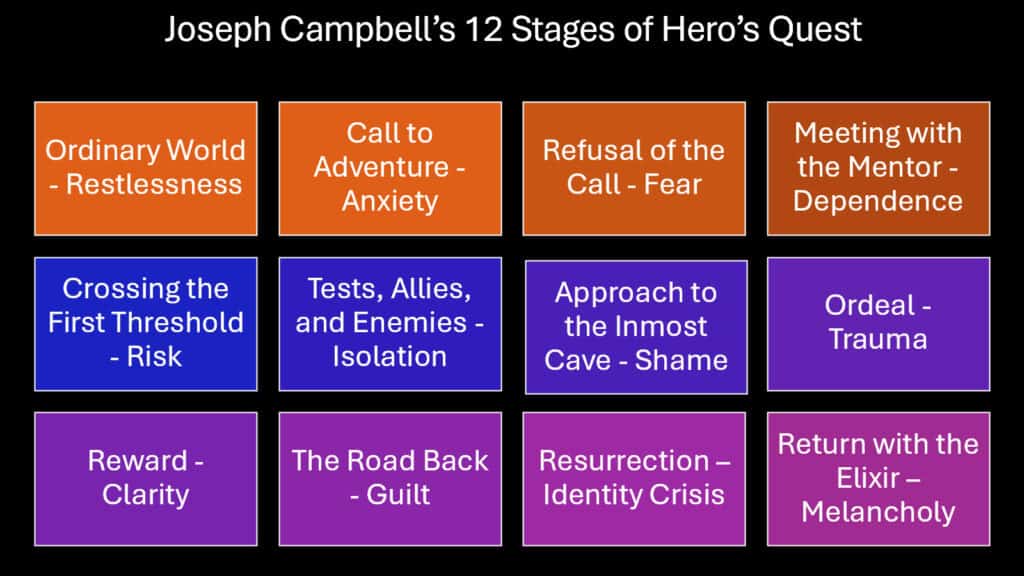

The stages of the Hero’s Quest can be mapped not by external events but by emotional transactions. The call to adventure costs the hero their comfortable ignorance. Crossing the threshold requires a sacrifice in the form of one’s familiar identity. Each trial along the way requires a different emotional coin—courage here, humility there, the willingness to be wrong somewhere else.

Consider how this emotional currency works in Homer’s Odyssey. Odysseus doesn’t just face physical challenges; he faces a series of emotional choices, each more costly than the last. When he blinds the Cyclops, he sacrifices his anonymity—his pride compels him to disclose his name, which results in Poseidon’s wrath being unleashed upon him. When he listens to the Sirens, he pays with his crew’s trust. When he finally reaches home, he must pay the ultimate price: the death of his old self.

The beauty of this system is that emotional currencies can’t be counterfeited. You can’t fake the kind of payment that true transformation requires. The hero either makes the genuine emotional exchange or the story stalls. This is why so many modern adaptations of classic Hero’s Quest narratives feel hollow—they preserve the external structure while gutting the emotional economy.

The return phase of the Hero’s Quest reveals the final cruel truth about emotional currencies: they don’t convert back. The wisdom purchased with suffering can’t be exchanged for the innocence that was lost. Frodo’s knowledge of the Ring’s weight can’t be traded for his old simple pleasure in the Shire. The hero comes back rich in ways that make them forever poor in others.

Table 3: Emotional Currency Exchanges in Major Hero’s Quest Stages

| Quest Stage | Emotional Currency Required | What Hero Gains | What Hero Loses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Call to Adventure | Comfort and security | Sense of purpose | Innocence and safety |

| Crossing Threshold | Familiar identity | Growth potential | Old sense of self |

| Tests and Trials | Pride and illusions | Wisdom and strength | Naive worldview |

| Death/Rebirth | Everything previously held dear | Transformed understanding | Original personality |

| Return Home | Ability to relate to old world | Integration of journey | Sense of belonging |

3. The Hero’s Quest and the Wound That Speaks

Trauma doesn’t move in straight lines. It spirals, circles back, revisits the same emotional territory from different angles. The Hero’s Quest, when understood through trauma theory, reveals itself as a narrative structure that mirrors this spiral pattern of healing—not the linear progression from wound to wholeness that popular psychology promises, but the complex dance of approach and avoidance that real recovery requires.

Cathy Caruth’s work on trauma theory illuminates something crucial about Hero’s Quest narratives: the stories that resonate most deeply are those that understand the impossibility of direct confrontation with certain kinds of wounds. Odysseus can’t simply sail home and forget about Troy. The trauma of war follows him, shapes every encounter, transforms every island into another battlefield where the past bleeds into the present.

The spiral structure of trauma processing appears throughout great Hero’s Quest narratives. Arjuna doesn’t resolve his moral crisis once and for all in his conversation with Lord Krishna. Throughout the Mahabharata, he returns again and again to questions of duty, righteousness, and the cost of action. Each return brings deeper understanding but never final resolution. The wound that speaks continues speaking, though its voice grows more nuanced with each spiral.

This is why the Hero’s Quest often feels repetitive to modern readers who expect linear character development. The protagonist appears to repeatedly learn the same lesson, confronting the same fears time and again. But trauma theory reveals this repetition as psychologically accurate. Healing happens not through single moments of insight but through countless small encounters with the wound, each one allowing a little more integration.

The unspeakable nature of trauma finds expression in the Hero’s Quest through symbols, dreams, and displacement. When Achilles encounters Patroclus in his dreams, pleading for a proper burial, the anguish of loss manifests in the only manner it can—indirectly, through images that possess emotional significance that the conscious mind cannot directly endure. The hero’s wound speaks through metaphor because direct speech would shatter the psyche.

Modern trauma theory’s emphasis on narrative healing—the idea that giving form to formless suffering is itself therapeutic—helps explain the enduring power of Hero’s Quest stories. These narratives don’t heal trauma by resolving it but by providing a structure within which trauma can be held, examined, and slowly integrated. The story becomes a container strong enough to hold what the individual psyche cannot bear alone.

Table 4: Trauma Theory Elements in Classic Hero’s Quest Narratives

| Trauma Theory Concept | Manifestation in Hero’s Quest | Literary Example | Healing Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repetition Compulsion | Hero faces similar challenges repeatedly | Odysseus encounters multiple sea monsters | Gradual mastery through repetition |

| Dissociation | Hero splits from normal identity | Jekyll and Hyde transformation | Integration of fractured self |

| Hypervigilance | Hero constantly scans for danger | Hamlet’s paranoid behavior | Learning to discern real threats |

| Narrative Fragmentation | Story told in non-linear fashion | Odyssey’s flashback structure | Piecing together coherent story |

| Somatic Memory | Body holds trauma beyond words | Achilles’ uncontrollable rage | Physical expression of emotional wound |

4. Silence as Storm: Emotional Subtext in the Hero’s Quest

The most powerful moments in any Hero’s Quest often happen in the spaces between words. When Arjuna sets down his bow and simply sits in his chariot, overwhelmed by the magnitude of the battle before him, his silence carries more emotional weight than any speech could bear. The pause contains everything—his love for his cousins, his duty as a warrior, his terror at the cost of righteousness.

This eloquence of silence appears throughout the greatest Hero’s Quest narratives, creating what might be called emotional subtext—the unspoken currents that carry the real story forward. In Homer’s Iliad, the most devastating moment isn’t Achilles’ rage-filled speeches but his silent weeping over Patroclus’ body. The absence of words creates space for grief too large for language.

Film adaptations often miss this crucial element, filling every pause with dialogue or action. But the literary Hero’s Quest understands that some emotions are too profound for direct expression. They require silence, stillness, the kind of pregnant pause that allows readers to feel the weight of what cannot be said. Think of Frodo’s long looks across Middle-earth, carrying meanings that would dissolve if spoken aloud.

The emotional subtext operates through what literary theorists call negative space—the areas where the story doesn’t go, the questions it doesn’t answer, the wounds it doesn’t probe directly. This negative space isn’t emptiness; it’s fullness that can’t be contained in language. When Odysseus finally reaches Ithaca and stands looking at his homeland after twenty years, the story doesn’t tell us what he’s thinking. It doesn’t need to. The silence says everything.

This technique appears across cultures in Hero’s Quest narratives. In Japanese storytelling, the concept of ma—meaningful pause or interval—serves similar functions. The hero’s journey includes not just action and dialogue but carefully orchestrated silences that allow emotional resonance to build. These pauses aren’t breaks in the story; they’re integral parts of its emotional architecture.

The power of emotional subtext lies in its ability to engage readers as co-creators of meaning. When the story leaves something unsaid, readers must fill that space with their own emotional understanding. This collaborative meaning-making creates deeper connection between reader and narrative, between individual experience and archetypal pattern. The silence becomes a bridge.

Table 5: Types of Meaningful Silence in Hero’s Quest Narratives

| Type of Silence | Emotional Function | Literary Example | Reader Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grief-struck Muteness | Processing overwhelming loss | Achilles over Patroclus’ body | Empathetic mourning |

| Moral Paralysis | Confronting impossible choices | Arjuna’s battlefield silence | Ethical contemplation |

| Awe-struck Wonder | Encountering the transcendent | Moses before burning bush | Spiritual recognition |

| Shame-filled Withdrawal | Dealing with moral failure | Peter’s denial aftermath | Self-examination |

| Exhausted Stillness | Reaching limits of endurance | Frodo in Mordor | Recognition of human limitation |

5. The Hero’s Quest as a Disintegrating Self

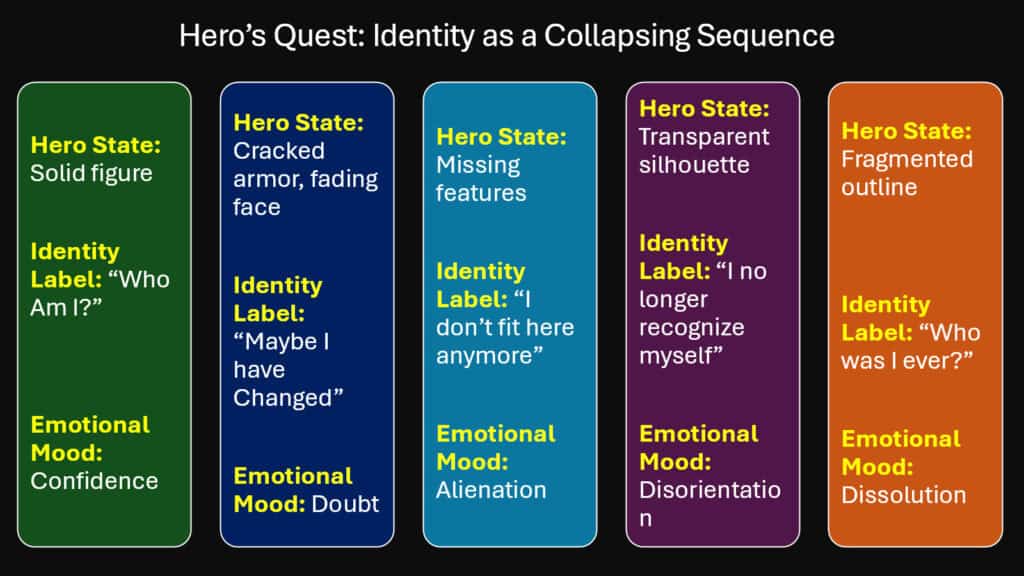

Post-structuralist theory shatters the comfortable myth of the unified self, and with it, the traditional reading of the Hero’s Quest as a journey toward wholeness. Instead of seeing heroes like Odysseus or Arjuna as individuals who overcome challenges to become complete, post-structuralism reveals them as fragmenting identities, collections of contradictory impulses and roles that can never fully cohere.

This lens transforms how we understand the Hero’s Quest’s emotional landscape. The journey doesn’t create a stronger, more integrated hero—it reveals the impossibility of integration itself. Achilles isn’t torn between competing desires for glory and survival; he is that tension, that unresolvable contradiction between mortal flesh and immortal ambition. His identity exists in the spaces between irreconcilable aspects of selfhood.

Jacques Derrida’s concept of différance—the idea that meaning is always deferred, never fully present—helps explain why Hero’s Quest narratives feel simultaneously conclusive and open-ended. Odysseus comes back to his homeland, yet the Odysseus who arrives is not the same individual who departed. The continuity of identity is revealed as linguistic convenience rather than psychological reality. The hero’s name remains constant while everything it signifies shifts.

This fragmentation creates a different kind of emotional power in Hero’s Quest narratives. Instead of the satisfaction of resolution, readers experience the vertigo of dissolution. When we follow Hamlet through his famous soliloquies, we’re not watching a character work through problems toward solutions—we’re watching selfhood unravel in real time, revealing the provisional nature of all identity.

The emotional weight in these stories comes not from the hero’s strength but from their instability. Each trial doesn’t strengthen the hero’s character so much as reveal new fault lines in the construction of selfhood. Frodo doesn’t become more heroic as he approaches Mount Doom—he becomes less coherent, more fragmented, until the self that began the journey has dissolved almost entirely.

Post-structuralist reading reveals why the return phase of the Hero’s Quest so often feels melancholy rather than triumphant. The hero comes back not as a integrated individual who has mastered their journey, but as a collection of traces, memories, and wounds that can never be assembled into a coherent whole. The return isn’t homecoming—it’s the final recognition that home, like self, was always already lost.

Table 6: Post-Structuralist Elements in Hero Identity Fragmentation

| Fragmentation Type | Theoretical Concept | Hero Example | Narrative Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Displacement | Identity across time | Odysseus (pre/post Troy) | Continuity illusion exposed |

| Role Multiplication | Multiple subject positions | Arjuna (son/warrior/student) | Unified self undermined |

| Linguistic Instability | Meaning always deferred | Hamlet’s wordplay | Communication breakdown |

| Cultural Dislocation | Identity tied to context | Moses between cultures | Belonging questioned |

| Moral Contradiction | Incompatible value systems | Achilles’ honor/vengeance | Ethical coherence impossible |

6. When the Elixir is Empty: The Final Emotional Paradox of the Hero’s Quest

The cruelest truth about the Hero’s Quest reveals itself at the moment of return. The hero comes back bearing what Campbell called the elixir—the wisdom or power that will heal the wounded land. But what happens when that elixir is empty? When the wisdom gained through suffering proves insufficient to the world’s wounds? When the hero’s transformation, complete and profound as it may be, cannot bridge the gap between who they have become and the world they left behind?

Frodo’s return to the Shire illuminates this final paradox most clearly. He has saved Middle-earth, completed the ultimate Hero’s Quest, but the Shire feels alien to him now. His sacrifice has been so complete that he can no longer inhabit the peace he has purchased for others. The elixir he brings back—wisdom about the true cost of good’s victory over evil—is too bitter for his neighbors to drink, too painful for him to bear.

This emotional paradox appears throughout great Hero’s Quest narratives, though it’s often overlooked in favor of more comfortable readings. Odysseus reaches Ithaca, but Homer’s poem ends with him slaughtering the suitors, transforming his homecoming into another battlefield. The hero who has learned the futility of violence through ten years of wandering immediately resorts to violence when faced with the mess his absence has created.

The empty elixir represents the most sophisticated understanding of what the Hero’s Quest actually offers: not solutions but deepened awareness of problems’ complexity. Arjuna doesn’t emerge from his conversation with Lord Krishna with clear answers about righteousness and duty. He emerges with a more nuanced understanding of how righteousness and duty can be irreconcilable, and the courage to act despite that irreconcilability.

This paradox explains why the greatest Hero’s Quest narratives often feel unsatisfying to modern readers trained to expect closure. The hero’s journey doesn’t end with problems solved but with problems transformed. The wound that initiated the quest may have healed, but healing has revealed new wounds, deeper complexities, more subtle forms of brokenness that require different kinds of attention.

The emotional power of this final paradox lies not in disappointment but in recognition. The Hero’s Quest reveals that some forms of knowledge are burdens rather than gifts, some kinds of growth are losses rather than gains. The hero returns not triumphant but transformed in ways that make triumph irrelevant. They carry not elixir but emptiness—and slowly, we learn that emptiness has its own kind of fullness.

Table 7: Manifestations of the Empty Elixir in Classical Narratives

| Hero | Expected Elixir | Actual Return | Emotional Paradox | Resolution Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frodo | Peace and healing | Inability to enjoy peace | Savior cannot be saved | Departure to Undying Lands |

| Odysseus | Restored kingdom | Continued violence | Wisdom doesn’t prevent repetition | Ongoing struggle |

| Achilles | Eternal glory | Regret in underworld | Fame feels hollow after death | Posthumous wisdom |

| Moses | Promised Land entry | Death before arrival | Leader excluded from destination | Sacrifice for others |

| Hamlet | Justice restored | Everyone dead | Truth’s cost exceeds value | Tragic recognition |

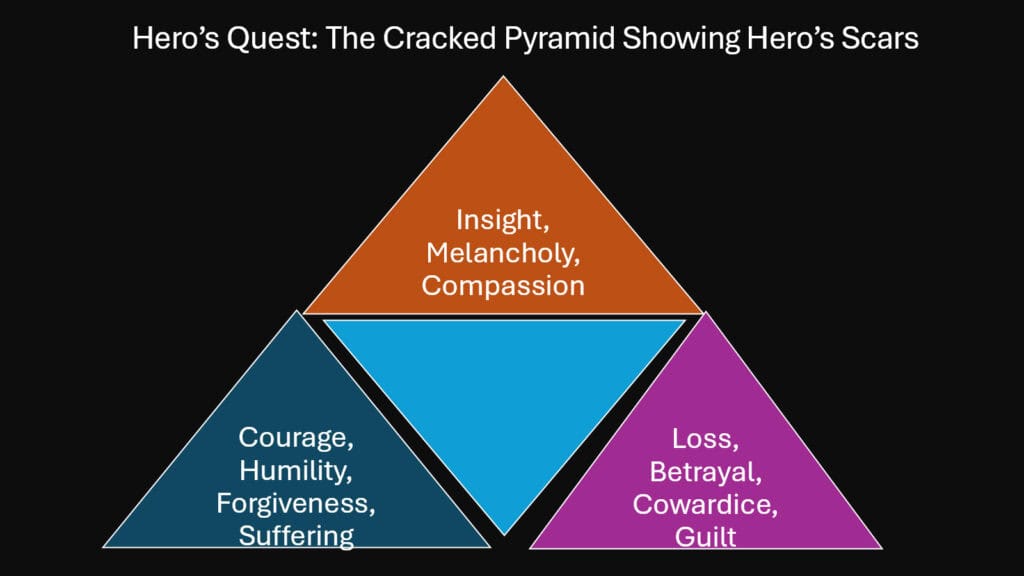

Conclusion: The Hero’s Quest and the Beauty of the Cracked Soul

The Hero’s Quest doesn’t teach us how to win. It teaches us how to lose beautifully, how to carry our defeats with dignity, how to find meaning in the spaces where meaning breaks down. Every hero we’ve examined—Arjuna paralyzed by moral complexity, Achilles consumed by grief-turned-rage, Odysseus haunted by the wages of pride, Frodo forever changed by burdens no one else can see—returns from their journey more broken than when they began, yet somehow more complete in their brokenness.

This is the radical wisdom that makes the Hero’s Quest perpetually relevant across cultures and centuries. It offers no false comfort, no easy answers, no promise that following the prescribed steps will result in healing or happiness. Instead, it provides something more valuable: a framework for understanding how brokenness can become a form of beauty, how wounds can become windows, how the very impossibility of wholeness can generate its own kind of perfection.

The six ways we’ve explored—archetypal griefwork, emotional currencies, trauma’s spiral pattern, the eloquence of silence, identity’s fragmentation, and the empty elixir—all point toward the same revolutionary insight. The Hero’s Quest succeeds not by solving the problem of human brokenness but by transforming our relationship to that brokenness. It teaches us to stop trying to fix ourselves and start learning to inhabit our cracks with grace.

This shift in perspective changes everything. When we stop reading these stories as blueprints for self-improvement and start reading them as meditations on the irreducible complexity of existence, they become not prescriptions but companions. They don’t tell us what to do; they sit with us in the difficulty of not knowing what to do. They don’t promise that courage will be rewarded; they demonstrate how courage can be its own reward, regardless of outcome.

The beauty of the cracked soul lies not in its potential for repair but in the way light moves through its fractures. Each break creates new possibilities for illumination, new angles from which to see old truths, new ways for inside and outside to meet. The Hero’s Quest maps these fault lines not as problems to be solved but as features of the landscape to be explored.

Perhaps this is why these ancient stories continue to speak to modern readers despite their archaic settings and seemingly outdated values. They address something in human experience that hasn’t changed: the fundamental challenge of being conscious in an unconscious universe, of seeking meaning in apparent meaninglessness, of loving in the face of inevitable loss. The Hero’s Quest offers no solutions to these challenges, but it provides invaluable company for those who must face them anyway.

Table 8: Integration of Brokenness Across Hero’s Quest Elements

| Quest Element | Type of Brokenness | Integration Method | Resulting Wisdom |

|---|---|---|---|

| Call to Adventure | Comfortable illusions shattered | Acceptance of reality’s complexity | Innocence transformed to experience |

| Mentor Encounter | Inadequacy of current knowledge | Humble openness to learning | Wisdom comes through not-knowing |

| Threshold Crossing | Old identity insufficient | Release of familiar self | Growth requires loss of previous self |

| Tests and Trials | Human limitations exposed | Perseverance despite weakness | Strength found in acknowledged vulnerability |

| Death and Rebirth | Total dissolution of ego | Surrender to transformation | New life requires death of old life |

| Return Home | Impossibility of going back | Creating new forms of belonging | Home becomes what we carry within |