Table of Contents

Introduction: Dilution Refrigerator as the Hidden Architect of Quantum Design

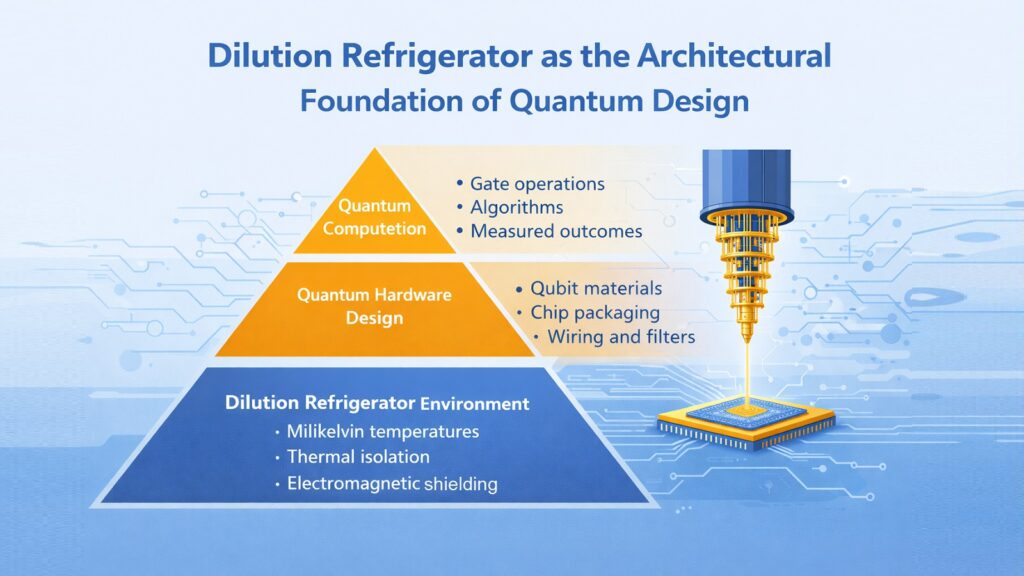

The design of quantum computers does not begin with qubits. It begins with the chamber that shapes their existence. The dilution refrigerator stands as the architectural constraint around which every quantum system must bend. Engineers do not first design a quantum processor and then find a way to cool it. They design around the refrigerator itself, accepting its geometry, its cooling limits, and its internal staging as the primary conditions of possibility. Quantum computing is not merely enabled by extreme cold. It is fundamentally structured by it.

The dilution refrigerator creates an environment approximately ten millikelvin above absolute zero. At this threshold, superconducting circuits lose resistance and quantum states stabilize long enough for computation. This is not incidental infrastructure. The refrigerator determines how many qubits can exist, where they can be placed, and how they can communicate with the outside world. Design choices that seem purely electronic or algorithmic are in fact thermal choices, dictated by the refrigerator’s capacity to remove heat without adding noise.

Understanding quantum design means understanding how refrigeration shapes scale, density, wiring, and layout. The quantum processor is not independent. It is an artifact of cryogenic engineering.

Dilution Refrigerator and Essential Pillars of Quantum Computer

| Component | Role in Quantum Computer |

|---|---|

| Dilution Refrigerator | Maintains millikelvin temperatures to enable superconductivity and suppress thermal noise across all quantum hardware stages |

| Qubits | Store and process quantum information through superposition and entanglement states at cryogenic temperatures |

| Microwave Control Lines | Transmit radiofrequency signals from room temperature to quantum chips while minimizing heat transfer through attenuation stages |

| Processor Chip | Houses physical qubits and coupling structures in superconducting circuits fabricated with nanometer precision |

| Vacuum and Shielding Systems | Isolate quantum hardware from electromagnetic interference, vibrations, and external radiation within cryogenic enclosures |

| Quantum Computer Gates | Manipulate qubit states through carefully timed microwave pulses calibrated to operate at millikelvin stability |

| Measurement Hardware | Amplifies weak quantum signals using cryogenic amplifiers positioned at multiple refrigerator temperature stages |

| Classical Control Systems | Generate precise timing and waveforms at room temperature while coordinating with cryogenic quantum hardware through filtered interfaces |

1. Dilution Refrigerator Sets the Physical Scale of Quantum Computers

Quantum computers are not built around their processors. They are built around the vessels that cool them. The size and internal structure of a dilution refrigerator establish the physical boundaries within which all quantum hardware must fit. Standard commercial dilution refrigerators offer between point four and point seven cubic meters of experimental volume at millikelvin temperatures. Larger systems under development push this to five cubic meters, but these remain rare. Every cubic meter matters because it determines how much quantum hardware can operate simultaneously.

The internal architecture consists of thermal stages descending from room temperature to the mixing chamber. Each stage operates at a progressively lower temperature: fifty kelvin, four kelvin, one hundred millikelvin, and finally the base temperature around ten millikelvin. Qubits must reside at the coldest stage, while supporting electronics are distributed across warmer plates according to their heat generation. This vertical staging is not flexible. It defines the modular structure of quantum systems. Engineers design processor modules to fit specific plates at specific temperatures. The refrigerator’s geometry forces a layered approach to quantum architecture rather than a horizontal scaling strategy.

Scale limitations become visceral when considering qubit counts. IBM’s Goldeneye system provides one point seven cubic meters of volume and can theoretically support around one thousand qubits with existing wiring technology. Fermilab’s Colossus offers five cubic meters and targets thousands of qubits. But volume alone does not determine capacity. Heat removal becomes the limiting factor. Commercial dilution refrigerators typically provide one milliwatt of cooling power at one hundred millikelvin. This constrains not just qubit count but the entire electronic ecosystem needed to control them. The refrigerator sets the scale before the first qubit is designed.

Dilution Refrigerator Physical Constraints on Quantum Scale

| Physical Parameter | Design Impact |

|---|---|

| Experimental Volume | Standard systems offer point four to point seven cubic meters at base temperature, limiting total hardware density and qubit packaging options |

| Thermal Stage Configuration | Multiple temperature plates from fifty kelvin to ten millikelvin force vertical component distribution across cooling stages |

| Mixing Chamber Dimensions | Typical three hundred to three hundred sixty millimeter diameter cold plates determine maximum processor chip and packaging sizes |

| Height and Access Geometry | Cylindrical or rectangular formats between two and four meters tall constrain wiring pathways and component accessibility |

| Cooling Power Budget | One milliwatt at one hundred millikelvin in commercial systems limits total allowable heat dissipation from all quantum hardware |

| Modular Insert Capacity | Side-loading secondary inserts accommodate wiring assemblies but add spatial constraints that restrict simultaneous qubit module expansion |

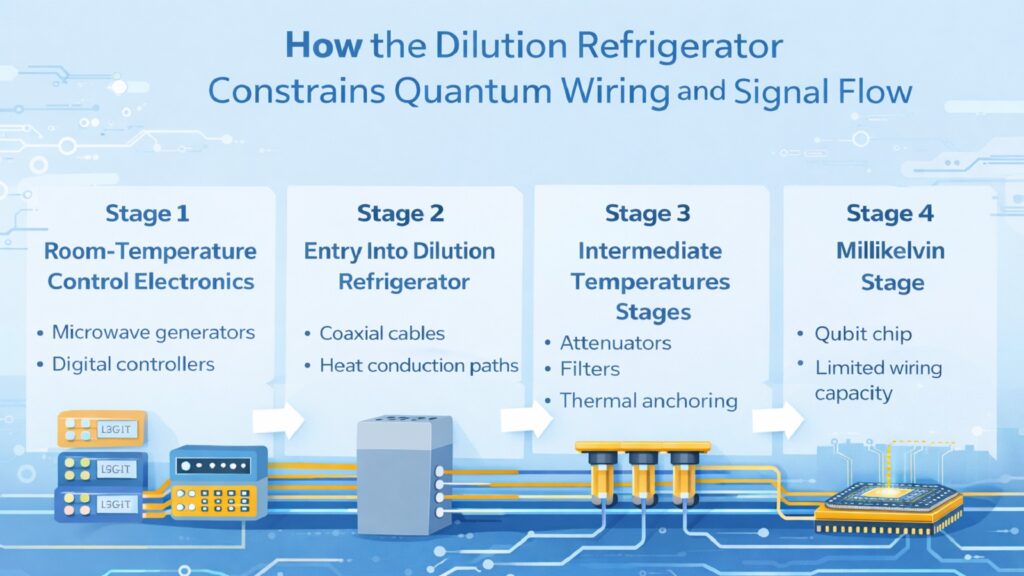

2. Dilution Refrigerator Dictates Wiring Density and Signal Routing

Every signal entering a dilution refrigerator carries heat. This simple fact dominates quantum computer design more than any other consideration. Control lines run from room temperature electronics down through multiple thermal stages to reach qubits at millikelvin temperatures. Each wire conducts thermal energy along its length. Add too many wires and the refrigerator loses its ability to maintain base temperature. The cooling system fails before the quantum computer scales.

A typical superconducting qubit requires two to three control lines. One for drive signals, one for flux tuning, and shared readout infrastructure. Multiply this by hundreds or thousands of qubits, and the thermal budget collapses. Research from recent thermal modeling studies shows that approximately one hundred fifty qubits can operate within the cooling capacity of standard dilution refrigerators when using conventional wiring approaches. Beyond this threshold, either the wiring density must improve, or multiple refrigerators become necessary. Both paths reshape quantum architecture fundamentally.

Solutions involve sophisticated cable engineering. High-density flexible wiring systems using phosphor bronze coated with superconducting materials reduce thermal conductivity while maintaining signal integrity. Multiplexing allows multiple qubits to share readout lines, cutting wire counts by factors of six or more. Researchers have demonstrated systems with nearly seven hundred control lines maintaining stable eight millikelvin base temperatures, but this required extensive thermal anchoring and custom attenuator placement at each stage. The dilution refrigerator does not merely cool. It enforces a strict energy accounting that limits complexity directly. Quantum scaling depends on solving wiring heat loads as much as improving qubit coherence.

Dilution Refrigerator Wiring Thermal Constraints

| Wiring Challenge | Design Consequence |

|---|---|

| Thermal Conductivity Limits | Each coaxial cable conducts heat proportional to its length and material, requiring careful selection between stainless steel and niobium-titanium based on temperature stage |

| Attenuation Heat Load | Signal attenuators must be distributed across multiple thermal stages to prevent concentration of dissipated power at cold plates |

| Control Line Density | Approximately one hundred fifty qubits can be wired conventionally before exceeding one milliwatt cooling power at one hundred millikelvin |

| Multiplexing Trade-offs | Readout line sharing reduces wire count by six-fold but introduces circuit complexity and potential crosstalk between qubit signals |

| Cable Routing Pathways | Physical space for cable bundles competes with sample holders, requiring custom wiring harnesses designed around refrigerator internal geometry |

| Active Heat Generation | Ohmic heating from signal transmission adds dynamic thermal loads that scale with qubit operation frequency and power levels |

3. Dilution Refrigerator Shapes Qubit Layout and Chip Architecture

Quantum processor chips do not occupy a neutral space. They exist within a thermal gradient imposed by the dilution refrigerator. The mixing chamber plate represents the coldest point, but temperature uniformity across its surface cannot be assumed. Thermal anchoring strategies determine where chips mount and how qubits distribute across the processor. Poor thermal contact raises local temperatures above design specifications, degrading qubit performance. Chip packaging and mounting hardware must account for thermal management before addressing any electrical considerations.

Qubit spacing reflects thermal realities as much as electromagnetic coupling requirements. Densely packed qubits generate local heat that accumulates faster than the refrigerator can remove it. This forces architectural choices about processor topology. Two-dimensional grid layouts maximize connectivity but create thermal hot spots. One-dimensional chain structures spread heat more effectively but limit gate operations between distant qubits. IBM’s heavy-hexagonal lattice represents a compromise, balancing coupling flexibility against thermal distribution. The refrigerator’s cooling profile shapes these fundamental design patterns.

Packaging strategies have evolved specifically around cryogenic constraints. Early quantum chips used simple wire bonding to printed circuit boards. Modern approaches employ multi-layer packaging with careful attention to thermal pathways. Beryllium copper mounting hardware provides both electrical grounding and heat conduction to the cold plate. Gold plating prevents oxidation that would create thermal resistance. Superconducting aluminum enclosures shield against radiation while operating below the one kelvin transition temperature. Every packaging detail serves thermal management because the dilution refrigerator demands it. Chip architecture follows from refrigeration first, then quantum mechanics second.

Dilution Refrigerator Influence on Qubit Chip Layout

| Thermal Design Factor | Architectural Response |

|---|---|

| Temperature Gradient Control | Processor chips mount on mixing chamber plates with beryllium copper hardware to ensure uniform ten to twenty millikelvin operation |

| Local Heat Accumulation | Qubit spacing must distribute active power dissipation to prevent thermal hot spots that degrade coherence times |

| Packaging Thermal Pathways | Multi-layer chip carriers use gold-plated surfaces and superconducting shields to manage heat flow while minimizing electromagnetic interference |

| Cold Plate Geometry | Three hundred millimeter diameter standard plates constrain maximum chip dimensions and force modular processor designs |

| Thermal Anchoring Requirements | Every signal line and structural element connecting to the chip requires thermal bonding at multiple refrigerator stages |

| Cryogenic Material Selection | Chip substrates, bonding materials, and enclosures must maintain properties at millikelvin temperatures while avoiding thermal contraction mismatches |

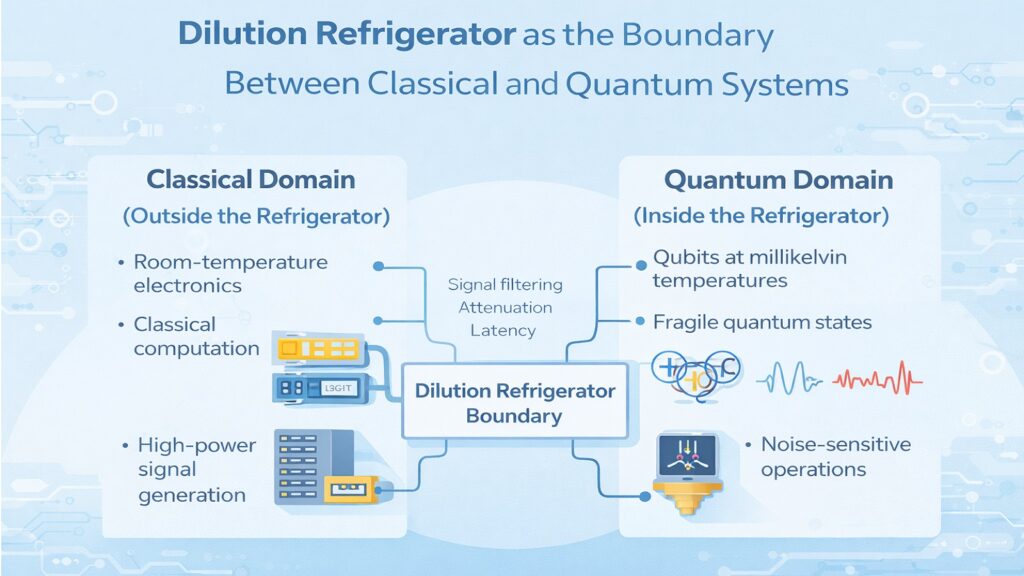

4. Dilution Refrigerator Separates Classical Control from Quantum Logic

The dilution refrigerator creates an absolute boundary between two computational domains. Room temperature electronics generate the signals that control qubits. Millikelvin hardware executes quantum operations. Between these realms lies a series of thermal stages that filter, attenuate, and condition every signal crossing the temperature divide. This separation is not merely physical. It represents a fundamental architectural constraint that shapes how quantum computers communicate with the classical world.

Signal degradation accumulates as control pulses traverse the refrigerator. Each thermal stage requires attenuators to reduce noise and prevent thermal radiation from reaching cold qubits. Attenuation at fifty kelvin, four kelvin, and mixing chamber stages can total thirty to forty decibels. This massive reduction means room temperature electronics must generate much stronger signals than qubits actually receive. The dilution refrigerator acts as a signal transformer, conditioning classical inputs into quantum-compatible forms. But this transformation introduces latency and constrains timing precision.

The reverse path from quantum hardware to classical readout faces different challenges. Weak qubit signals must be amplified without adding noise. Cryogenic amplifiers positioned at the mixing chamber provide initial gain at quantum-limited noise levels. Subsequent amplification at four kelvin and room temperature stages boosts signals to detectable levels. This cascade of amplification stages exists because the dilution refrigerator separates quantum from classical domains across multiple temperature zones. Control architectures must account for these fixed boundaries. Hybrid systems, placing some electronics at four kelvin, reduce wiring and improve latency, but the fundamental separation imposed by cryogenic staging remains. Quantum design must always negotiate with this imposed structure.

Dilution Refrigerator Control-Quantum Hardware Separation

| Boundary Condition | System Design Requirement |

|---|---|

| Temperature Stage Filtering | Signals cross four to six thermal stages requiring attenuators and filters at each level to block noise propagation |

| Latency Accumulation | Signal travel time through cable lengths and component chains introduces nanosecond-scale delays affecting gate timing precision |

| Amplification Cascade | Quantum readout requires three-stage amplification with traveling wave parametric amplifiers at mixing chamber and semiconductor amplifiers at four kelvin |

| Signal Conditioning | Room temperature electronics must pre-compensate for cable dispersion and thermal effects occurring across refrigerator stages |

| Power Budget Partitioning | Control electronics dissipating more than one milliwatt must remain at warmer stages, forcing distributed architecture designs |

| Classical-Quantum Interface | Hybrid control chips operating at four kelvin mediate between room temperature systems and millikelvin qubits to reduce wiring bottlenecks |

5. Dilution Refrigerator Limits Quantum Scaling and Expansion

Scaling quantum computers confronts a hard physical limit. The dilution refrigerator’s cooling power determines maximum system size. This constraint operates differently from classical computing bottlenecks. Adding more qubits does not merely increase cost or complexity. It fundamentally threatens the thermal equilibrium needed for quantum operation. Standard commercial dilution refrigerators cannot support fault-tolerant quantum computing, which requires millions of physical qubits. The refrigeration technology itself must evolve before quantum computers reach practical utility.

Consider the mathematics of heat removal. Each qubit contributes passive thermal load through its control wiring. Active load comes from signal dissipation during gate operations. Sum these across one thousand qubits and the total approaches or exceeds the one milliwatt cooling capacity at one hundred millikelvin. Beyond this point, base temperature rises. Qubit coherence degrades. The system fails. Researchers developing larger refrigerators like Fermilab’s Colossus target ten times more cooling power specifically to overcome this scaling barrier. But even these systems face limits. Doubling cooling capacity does not double usable qubits because wiring density and space constraints compound.

Alternative approaches involve connecting multiple dilution refrigerators. Oxford Instruments developed patented technology for joining rectangular refrigerators into unified systems with shared vacuum space and connected cold plates. This allows quantum processors in separate refrigerators to interact without routing signals through room temperature interfaces. Such multi-refrigerator architectures acknowledge that single-vessel scaling has physical limits. Quantum computing may require distributed refrigeration at scale, with networks of cooled chambers rather than ever-larger single units. The dilution refrigerator defines both the promise and the ceiling of quantum scaling simultaneously.

Dilution Refrigerator Scaling Limitations

| Scaling Constraint | Impact on Quantum Expansion |

|---|---|

| Cooling Power Ceiling | One milliwatt at one hundred millikelvin in standard systems limits total qubit count to hundreds before thermal capacity exhausts |

| Heat Load Accumulation | Passive wiring thermal loads plus active signal dissipation scale linearly with qubit number, overwhelming fixed cooling power |

| Volume vs Cooling Trade-off | Larger experimental volumes require proportionally greater cooling capacity, making single-refrigerator scaling increasingly inefficient |

| Multi-Refrigerator Coordination | Connecting qubits across separate dilution refrigerators requires microwave-optical transduction or cryogenic interconnects with associated losses |

| Fault-Tolerant Requirements | Quantum error correction demands millions of physical qubits, exceeding any foreseeable single-refrigerator cooling capacity by orders of magnitude |

| Cryogenic Infrastructure Cost | Scaling cooling power beyond ten milliwatts requires custom systems costing millions of dollars, limiting accessibility and deployment scenarios |

6. Dilution Refrigerator Reduces Noise Before Error Correction Begins

Quantum error correction operates on assumptions that depend entirely on the dilution refrigerator. Error correction algorithms assume that qubits maintain coherence long enough for multiple correction cycles to complete. They assume thermal noise remains below thresholds where correction codes can outpace error accumulation. These assumptions only hold because dilution refrigerators suppress environmental interference before software-level correction begins. The refrigerator provides the foundation upon which error correction becomes mathematically viable.

Thermal noise at room temperature would excite superconducting qubits out of their ground states immediately. At three hundred kelvin, thermal energy is twenty-five millielectronvolts. Qubit transition energies are only a few gigahertz, corresponding to microelectronvolts. Without refrigeration, thermal occupation numbers would be enormous. Qubits would randomize faster than any gate operation could complete. Cooling to ten millikelvin reduces thermal energy by thirty thousand times. This brings thermal photon numbers below point zero one, creating an environment where quantum states persist long enough to be useful.

Error correction cannot compensate for overwhelming thermal noise. It corrects residual errors that survive despite refrigeration. Recent experiments achieving coherence times exceeding four hundred microseconds still required dilution refrigerator temperatures. These long coherence times enable surface codes and other topological error correction schemes. But the math works only because the refrigerator already suppressed noise to levels where correction overhead remains reasonable. Quantum design must treat refrigeration as the primary error suppression mechanism. Software correction extends what refrigeration makes possible. It does not replace it. The dilution refrigerator shapes quantum computing at the most fundamental layer by making error correction tractable rather than impossible.

Dilution Refrigerator Noise Suppression for Error Correction

| Noise Reduction Mechanism | Error Correction Enablement |

|---|---|

| Thermal Photon Suppression | Cooling to ten millikelvin reduces thermal occupation numbers to less than point zero one, preventing random qubit excitation |

| Coherence Time Extension | Millikelvin operation enables transmon coherence times exceeding two hundred microseconds, allowing multiple error correction cycles |

| Decoherence Rate Reduction | Ultra-low temperatures minimize energy relaxation and dephasing rates to thresholds where quantum error correction overhead remains feasible |

| Background Noise Floor | Cryogenic environment lowers electromagnetic and vibrational noise below qubit sensitivity, creating stable baseline for error detection |

| Qubit Lifetime Enhancement | Superconducting circuits achieve quality factors above five million at dilution refrigerator temperatures, providing extended operational windows |

| Error Correction Threshold Reach | Physical error rates drop below one percent when thermal noise suppression combines with electromagnetic shielding at millikelvin temperatures |

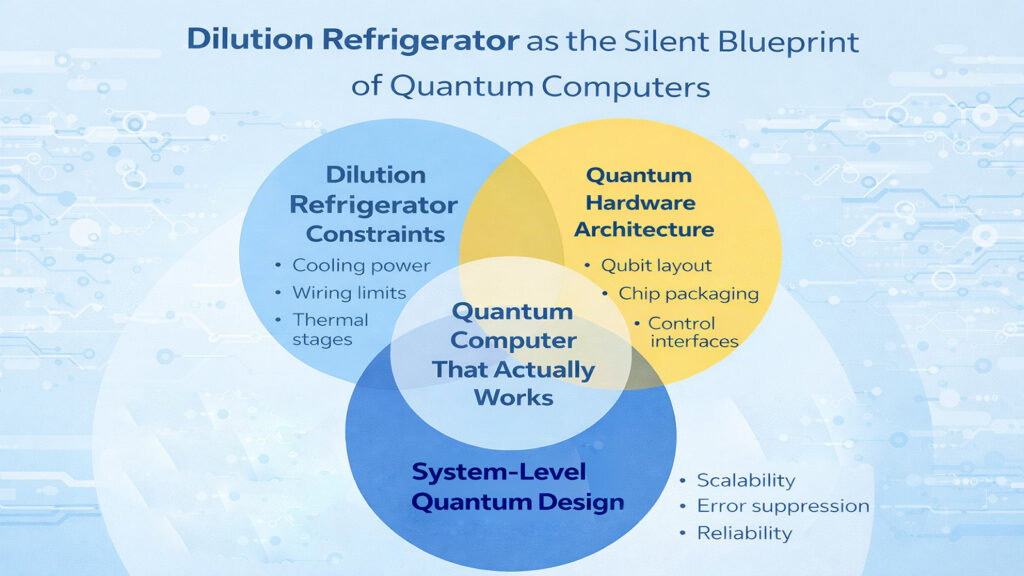

Conclusion: Dilution Refrigerator as the Silent Blueprint of Quantum Design

Quantum computers are not cooled by dilution refrigerators. They are essentially shaped by them. The refrigerator’s geometry determines scale. Its cooling power limits complexity. Its thermal stages impose control architecture. Its wiring capacity constrains qubit count. Every aspect of quantum design responds to refrigeration requirements before addressing considerations of quantum mechanics. The processor is not independent of its vessel. It is an artifact of cryogenic engineering realized within specific thermal boundaries.

This reality will intensify as quantum computing advances. Current systems operate hundreds of qubits within existing refrigerator technology. Fault-tolerant quantum computing requires millions. No single refrigerator can provide this capacity. Future architectures will likely involve refrigerator networks, distributed cooling, and entirely new cryogenic approaches. Quantum scaling depends on refrigeration innovation as much as qubit improvement. The two cannot be separated.

The dilution refrigerator stands as the hidden architect. It shapes what quantum computers look like, how they operate, and what scales they can reach. Breakthroughs in quantum computing will increasingly come from cryogenic engineering rather than quantum theory alone. Understanding this relationship clarifies why quantum design proceeds as it does. The refrigerator came first. Everything else followed.

Dilution Refrigerator as Foundation of Future Quantum Design

| Design Evolution | Refrigeration Innovation Requirement |

|---|---|

| Scaling Beyond Thousands of Qubits | Connected multi-refrigerator systems with shared vacuum and cold plate integration to distribute thermal loads |

| Reduced System Footprint | Modular rectangular geometries replacing cylindrical designs to enable data center deployment and maintenance efficiency |

| Higher Cooling Power | Custom dilution systems providing ten to fifty milliwatts at mixing chamber to support fault-tolerant quantum processors |

| Improved Wiring Density | Superconducting flex cables and high-density interconnects reducing per-qubit thermal contribution by orders of magnitude |

| Cryogenic Control Integration | Quantum control electronics operating at four kelvin or below to minimize room-temperature interface requirements |

| Long-Term Stability | Refrigeration systems maintaining millikelvin temperatures for months without interruption to support continuous quantum operations |

Read More Tech Articles

- Intelligent Robotics: 6 Powerful Ways AI Comes Alive

- Natural Language Processing: 6 Powerful Ways AI Reads

- Machine Learning in AI: 6 Powerful Ways AI Learns

- Artificial Intelligence: 8 Powerful Insights You Must Know

- Quantum Computing: 6 Powerful Concepts Driving Innovation

- 8 Powerful Smart Devices To Brighten Your Life

- 8 E-Readers: Epic Characters in a Library Adventure

- Smart TV Brands: 8 Epic Directors for Screen Magic

- Tablet Brands as Superheroes: 8 Amazing Tech Avengers

- Discover 8 Smart Speaker Brands As Motivational Speakers

- 8 Amazing Fitness Tracker Brands as Story Characters

- Laptop Brands as Celebrities: Meet 8 Alluring Stars