Table of Contents

Introduction: The Hidden Architecture of Global Economic Governance

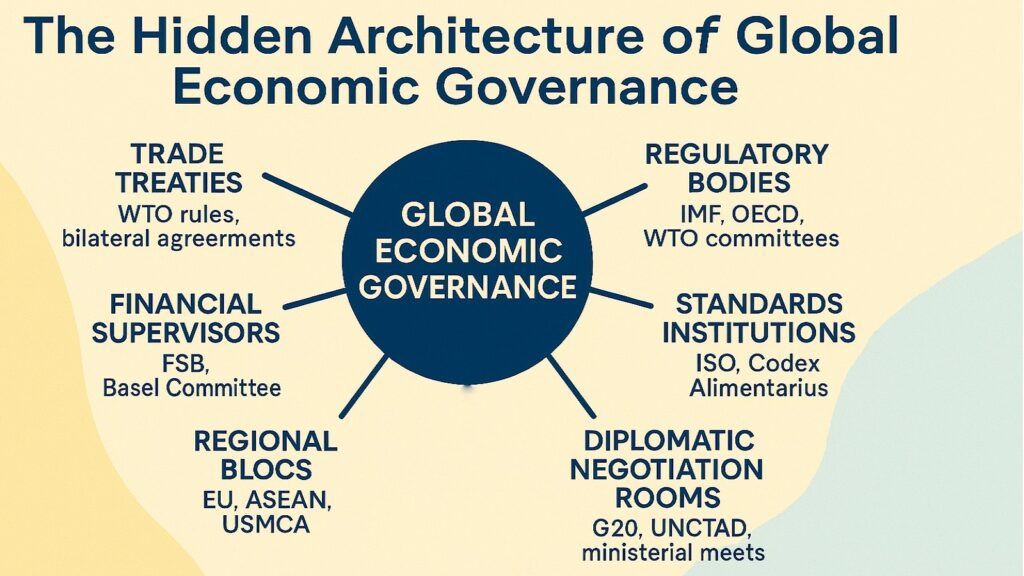

Behind every transaction that crosses a border lies an intricate web of rules most people never see. Global Economic Governance represents this invisible architecture. It shapes how nations trade, how businesses invest, and how markets function across continents. These frameworks emerge from treaties negotiated in quiet conference rooms, from regulations drafted by committees, and from standards agreed upon by technical experts. Yet their influence radiates outward, touching supply chains, employment patterns, and the prices consumers pay.

The system operates through layers. International institutions set baseline rules. Regional agreements carve out special arrangements. National governments translate broad principles into enforceable laws. This multi-tiered structure determines which goods flow freely and which face barriers, which services can be delivered across borders and which remain confined to domestic markets.

Understanding Global Economic Governance means recognizing how these forces interact with other building blocks of the global economy. Trade flows follow paths carved by governance structures. Financial systems operate within regulatory boundaries. Technology spreads through channels shaped by international agreements.

How Global Economic Governance Connects to The Core of Global Economic Building Blocks

| Building Block | Relationship to Global Economic Governance |

|---|---|

| Global Trade | Establishes tariff schedules, quotas, and dispute mechanisms determining cross-border flows |

| Labor Migration | Sets international labor standards and bilateral agreements shaping workforce mobility |

| Global Tech Innovation | Governs patent treaties, data transfer rules, and intellectual property protection |

| Natural Resources and Global Energy | Regulates resource extraction agreements and commodity pricing mechanisms |

| Global Financial Systems | Determines banking regulations, capital controls, and payment system standards |

| Global Supply Chain | Influences rules of origin, customs procedures, and logistics standards |

| Geopolitics | Reshapes trade patterns through strategic alliances and sanctions regimes |

| Demographics | Interacts with migration policies and labor market regulations |

| Climate and Sustainability | Functions through carbon pricing systems and environmental standards |

1. Global Economic Governance and the Power of Multilateral Institutions

Four organizations stand at the center of Global Economic Governance. The World Trade Organization writes the rulebook for international commerce. The International Monetary Fund acts as a lender and policy advisor during financial crises. The World Bank channels development finance toward infrastructure and poverty reduction. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development coordinates policy among advanced economies.

The WTO’s influence extends through its dispute settlement mechanism. When countries clash over trade practices, panels examine evidence and issue binding rulings. These decisions create precedents that guide future behavior. A ruling against agricultural subsidies affects farming policies worldwide. The system processes dozens of disputes annually, each one clarifying boundaries and refining interpretations.

The IMF’s role becomes most visible during crises. When nations face currency collapse or sovereign debt default, the Fund provides emergency loans tied to policy conditions. These conditions typically require fiscal austerity, structural reforms, and market liberalization. IMF programs affect millions of lives and reshape entire economies.

The World Bank operates differently, focusing on long-term development. It finances ports, power plants, education systems, and health programs in developing countries. This financing comes with governance requirements for environmental protection, social safeguards, and procurement procedures. These requirements effectively export governance norms from wealthy nations to poorer ones.

The OECD serves as a forum where rich countries coordinate policies. Its committees develop guidelines for taxation, competition policy, anti-bribery measures, and corporate governance. While technically non-binding, these guidelines carry weight because they represent consensus among major economies. Countries seeking foreign investment often adopt OECD standards to signal credibility.

Major Multilateral Institutions Shaping Global Economic Governance

| Institution | Core Governance Function |

|---|---|

| World Trade Organization | Administers trade agreements and resolves disputes across 164 member countries |

| International Monetary Fund | Provides crisis loans with policy reforms and monitors global financial stability |

| World Bank | Finances development projects while setting environmental and social standards |

| OECD | Develops policy guidelines on taxation, competition, and corporate governance |

| Bank for International Settlements | Coordinates banking regulations through Basel frameworks and capital standards |

| UNCTAD | Advocates for developing country interests in trade negotiations |

2. Global Economic Governance and Regulatory Harmonization Across Borders

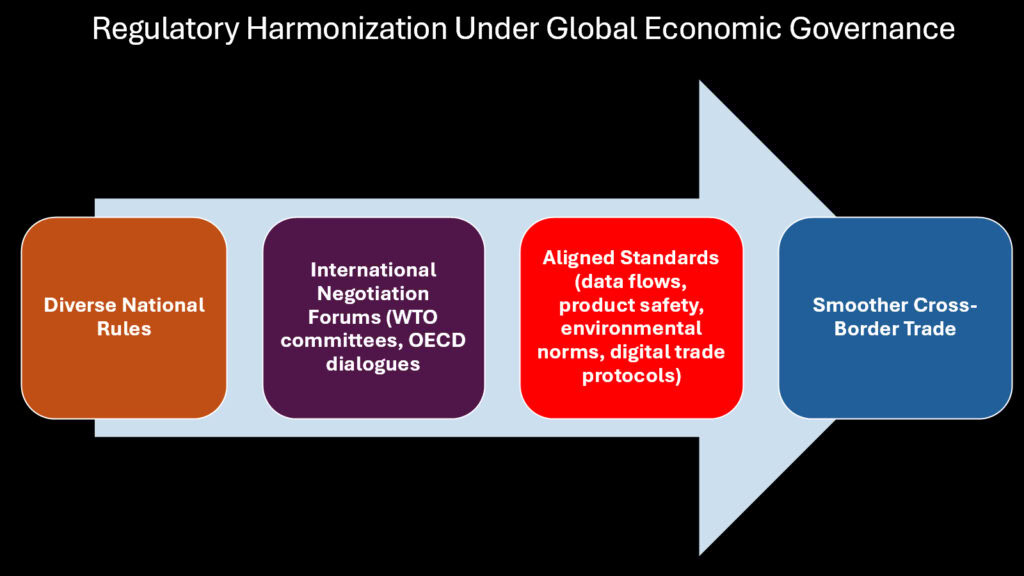

Products sold across borders must meet standards in every market they enter. A toy manufactured in Vietnam must comply with European safety requirements if sold in France, American regulations if sold in California, and Japanese standards if sold in Tokyo. This multiplicity creates costs. Harmonization addresses this problem by aligning standards across countries.

The process unfolds through technical committees and international standard-setting bodies. Engineers and scientists from different nations gather to debate specifications for everything from electrical connectors to food additives. They negotiate acceptable contamination levels, testing methodologies, and labeling requirements. The resulting standards become reference points that national regulators adopt.

Mutual recognition agreements offer an alternative approach. Rather than harmonizing standards, countries agree to accept each other’s certifications. A product approved by German regulators automatically gains approval in Australia. These agreements work best between countries with similar regulatory philosophies.

Data governance presents newer harmonization challenges. The European Union requires strict consent procedures and grants individuals extensive control over personal data. China mandates that certain data categories remain stored within national borders. The United States favors lighter-touch regulation. These differences fragment global digital markets.

Environmental standards show both promise and limits of harmonization. International agreements set baseline targets for emissions reductions, chemical safety, and waste management. Yet implementation varies dramatically. Some countries enforce standards strictly while others treat them as aspirational goals. This variation creates competitive distortions.

Key Areas of Regulatory Harmonization in Global Economic Governance

| Regulatory Domain | Harmonization Mechanism |

|---|---|

| Product Safety | ISO and IEC develop technical specifications reducing duplicate testing |

| Pharmaceutical Approval | ICH aligns drug development processes accelerating medicine access |

| Financial Services | Basel Committee establishes capital requirements across 70+ countries |

| Food Safety | Codex Alimentarius sets international food standards as WTO reference |

| Telecommunications | ITU coordinates wireless standards enabling global device interoperability |

| Chemical Management | GHS standardizes hazard communication facilitating safer chemical trade |

3. Global Economic Governance and the Rise of Digital Trade Rules

Digital commerce has outpaced the rules meant to govern it. When nations negotiated the WTO agreements in the 1990s, e-commerce barely existed. Cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and platform businesses were science fiction. Now these technologies drive economic growth and international trade.

Data represents the central tension. Companies argue that data must flow freely to enable efficient operations. Governments worry about national security, privacy protection, and domestic industry development. China restricts data transfers to maintain control over information. The European Union limits data exports to countries lacking adequate privacy protections. Each approach reflects different priorities and creates barriers.

E-commerce taxation illustrates governance gaps. When consumers buy digital products from foreign suppliers, who collects sales tax? Traditional rules assumed that physical presence determined tax jurisdiction. Digital businesses shattered this assumption. Many countries now require foreign digital companies to register for tax purposes, but implementation varies widely.

Payment systems face fragmented regulation. Moving money across borders triggers anti-money-laundering checks, foreign exchange controls, and consumer protection requirements. Digital payment platforms must obtain licenses in every market they enter. Some countries restrict foreign ownership of payment infrastructure.

Artificial intelligence regulation represents the newest frontier. The European Union’s AI Act categorizes applications by risk level and imposes requirements accordingly. China’s approach emphasizes government approval and algorithm registration. The United States favors sector-specific rules and industry self-regulation. These divergent frameworks will shape where AI companies locate operations.

Digital Trade Governance Frameworks in Global Economic Governance

| Framework Component | Implementation Challenge |

|---|---|

| Cross-Border Data Flows | EU GDPR limits transfers while 70+ countries impose localization requirements |

| Digital Services Taxation | OECD Two-Pillar Solution negotiated by 140+ jurisdictions on revenue allocation |

| E-Commerce Consumer Protection | UNCITRAL Model Law provides framework but enforcement remains weak |

| Digital Copyright | WIPO Internet Treaties address online rights though piracy enforcement lags |

| Cybersecurity Standards | NIST framework widely adopted but incident reporting requirements differ |

| Platform Liability | EU Digital Services Act contrasts sharply with US Section 230 safe harbors |

4. Global Economic Governance and Supply Chain Security Frameworks

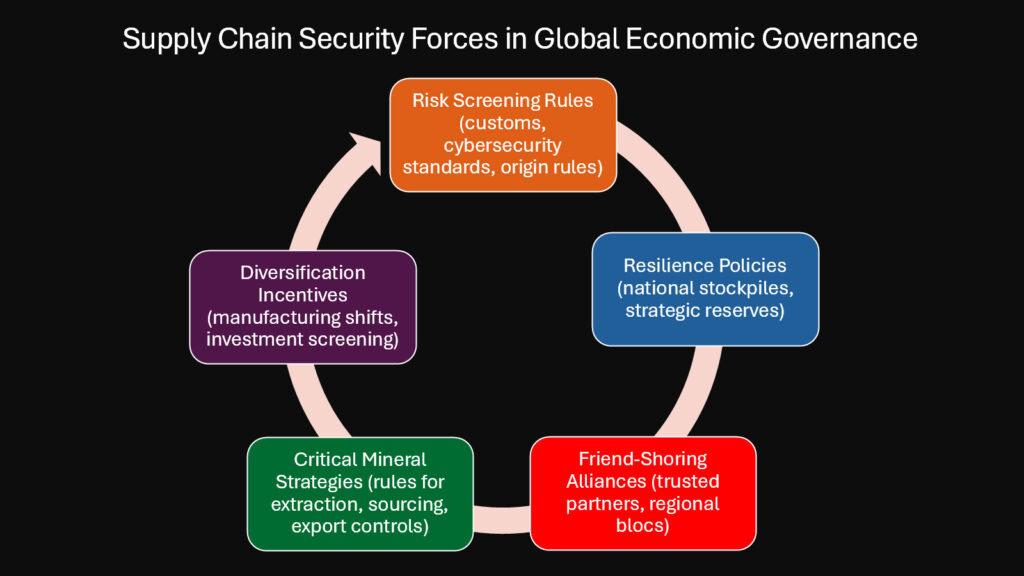

Supply chains span continents, linking raw material extraction in one region to component manufacturing in another and final assembly in a third. This geographic dispersion creates efficiency but also vulnerability. Pandemic disruptions revealed how quickly shortages cascade globally. Nations now redesign supply chains with resilience and security as priorities.

Friend-shoring represents one strategic response. Instead of sourcing from the lowest-cost supplier regardless of location, companies prioritize suppliers in allied countries. The United States encourages semiconductor manufacturers to build facilities domestically or in partner nations. The European Union seeks to reduce dependence on Chinese suppliers for batteries and renewable energy components.

Critical minerals present acute governance challenges. Electric vehicles, renewable energy systems, and advanced electronics depend on lithium, cobalt, rare earths, and other materials concentrated in few locations. China dominates processing of many critical minerals even when deposits exist elsewhere. Alternative supply chains require coordinating mining, processing, and manufacturing across multiple countries.

Screening mechanisms for foreign investment grew more stringent. Many countries now review acquisitions of domestic companies by foreign investors, particularly in sectors deemed strategically important. Technology, infrastructure, defense, and critical materials face heightened scrutiny.

Export controls on advanced technologies expanded beyond traditional military applications. The United States restricts sales of cutting-edge semiconductors and chip-making equipment to China. The Netherlands and Japan joined these controls despite economic costs. These restrictions fragment global technology markets.

Supply Chain Security Mechanisms in Global Economic Governance

| Security Mechanism | Implementation Impact |

|---|---|

| Foreign Investment Screening | CFIUS reviews 200+ transactions annually; EU coordinates through FDI Regulation |

| Critical Minerals Partnerships | 14-country Minerals Security Partnership coordinates lithium and rare earth investments |

| Export Control Coordination | Wassenaar Arrangement among 42 countries harmonizes dual-use technology controls |

| Supply Chain Due Diligence | EU Directive requires companies to identify forced labor and environmental risks |

| Port Security Initiatives | Container Security Initiative pre-screens cargo at 80+ ports worldwide |

| Semiconductor Alliances | CHIPS Act and EU Chips Act provide $100+ billion to reshore production |

5. Global Economic Governance and the Influence of ESG & Sustainability Standards

Environmental, social, and governance standards once operated at the margins of business decision-making. That world has changed. ESG considerations now affect access to capital, supply chain relationships, and market entry. What began as voluntary corporate social responsibility evolved into a governance framework with teeth.

Climate disclosure requirements lead this transformation. Stock exchanges and securities regulators increasingly mandate that companies report greenhouse gas emissions, climate risks, and transition plans. The European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive requires detailed environmental and social disclosures from large companies. Global standards from the International Sustainability Standards Board provide a framework many jurisdictions will adopt.

Carbon pricing mechanisms translate environmental goals into economic signals. The European Union’s Emissions Trading System caps total emissions from covered sectors and allows companies to trade allowances. China operates the world’s largest carbon market covering power generation. Canada implements federal carbon pricing with revenues returned to households.

Carbon border adjustments extend carbon pricing internationally. The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism imposes fees on imports of cement, steel, aluminum, fertilizer, electricity, and hydrogen based on their carbon intensity. It aims to prevent carbon leakage where production shifts to jurisdictions without carbon pricing.

Labor standards increasingly function as trade conditions. Trade agreements now routinely include labor chapters requiring signatories to uphold core International Labour Organization conventions. The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement includes rapid response mechanisms allowing investigation of labor violations at specific facilities.

Supply chain transparency requirements push ESG obligations upstream. Laws in several jurisdictions require companies to identify and address forced labor, child labor, and environmental damage in their supply chains. The EU’s deforestation regulation bans products linked to forest destruction.

ESG Standards as Global Economic Governance Mechanisms

| ESG Domain | Governance Instrument |

|---|---|

| Climate Disclosure | ISSB framework adopted by jurisdictions representing 40%+ of global GDP |

| Carbon Pricing | 75 initiatives worldwide cover 24% of global emissions; EU permits exceed €80/ton |

| Deforestation | EU regulation requires importers verify coffee, cocoa, soy, palm oil sourcing |

| Forced Labor | India uses the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976 as a key legal instrument to prohibit forced labour, free bonded workers, and penalize those who exploit them. |

| Green Finance | EU Taxonomy defines sustainable activities influencing trillions in investment |

| Scope 3 Emissions | California requires reporting indirect supply chain and product use emissions |

6. Global Economic Governance and the Geopolitical Forces Redefining Trade

Trade rules reflect power relationships. When the United States and its allies dominated the global economy after World War II, they designed institutions serving their interests. Rising powers like China now challenge this order. Strategic competition reshapes commercial relationships. The fiction that economics and politics operate separately has dissolved.

Sanctions weaponize economic interdependence. The United States leverages the dollar’s role in international finance to enforce sanctions against Iran, Russia, North Korea, and other adversaries. Banks worldwide avoid sanctioned entities to preserve access to the American financial system. Russia’s exclusion from SWIFT payment messaging after its invasion of Ukraine demonstrated the power of financial sanctions.

Export controls on advanced technologies intensify. The United States restricts sales of cutting-edge semiconductors and chip-making equipment to China, aiming to slow its military modernization. The Netherlands and Japan joined these controls. China responds by restricting exports of gallium and germanium, materials critical for advanced electronics.

Regional trade agreements multiply as multilateral negotiations stall. The WTO has not concluded a major trade round since the 1990s. Instead, countries negotiate preferential deals with select partners. The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership links eleven Pacific Rim nations. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership connects fifteen Asia-Pacific economies.

Technology standards become geopolitical battlegrounds. The competition between Chinese and Western telecommunications equipment suppliers concerns more than market share. It determines which technical standards govern next-generation networks. Similar contests play out in artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and biotechnology.

Investment screening politicizes capital flows. During the era of economic integration, cross-border investment was mostly welcomed. Now major economies carefully scrutinize foreign investment for strategic implications. Chinese acquisitions of Western technology companies face tough reviews.

Geopolitical Instruments Reshaping Global Economic Governance

| Geopolitical Tool | Strategic Application |

|---|---|

| Financial Sanctions | US OFAC maintains 30+ programs affecting thousands of entities globally |

| Technology Export Controls | BIS restrictions on semiconductors and AI systems fragment technology supply chains |

| Strategic Trade Partnerships | Indo-Pacific Economic Framework brings 14 countries representing 40% of global GDP |

| Infrastructure Security | Five Eyes alliance coordinates on limiting Chinese telecom equipment in 60+ countries |

| Resource Export Restrictions | China controls 80%+ of rare earth processing; Indonesia banned nickel ore exports |

| Regional Development Finance | China’s Belt and Road Initiative financed $1+ trillion in infrastructure across 150 countries |

Conclusion: The Future Path of Global Economic Governance in a Fragmenting World

The architecture of Global Economic Governance stands at an inflection point. For decades, the trajectory seemed clear: deeper integration, lower barriers, more harmonized rules, and stronger multilateral institutions. That vision no longer commands consensus. Instead, multiple models compete. Strategic considerations override efficiency arguments.

Climate change demands unprecedented international cooperation precisely when geopolitical tensions undermine trust. Digital technologies require harmonized rules across jurisdictions even as nations jealously guard data sectors. Supply chain resilience needs diversification at odds with efficiency-maximizing concentration. These contradictions ensure that Global Economic Governance will remain contested terrain.

The institutions built after World War II struggle to accommodate new powers and new challenges. The WTO’s dispute settlement system has been paralyzed. The IMF’s governance structure still reflects the economic balance of 1945. Reform proves difficult because those who benefit from current arrangements resist change.

Regional and plurilateral arrangements will likely fill governance gaps that multilateral institutions cannot address. Climate clubs linking countries with similar ambitions can move faster than consensus negotiations. Digital trade agreements among like-minded partners can establish rules while broader frameworks remain elusive. This variable geometry approach allows progress but creates complexity.

The next generation of Global Economic Governance will likely feature more conditional openness, more explicit reciprocity, and more differentiation among partners. Market access will depend increasingly on meeting standards for labor, environment, data protection, and security. The invisible architecture that shapes global commerce will become more visible as it grows more complex and contested.

Emerging Governance Challenges for Economic Governance

| Challenge Domain | Key Governance Gap |

|---|---|

| Digital Currency Regulation | 130+ countries developing CBDCs require interoperability standards currently lacking |

| Artificial Intelligence | Divergent EU, China, US approaches threaten to fragment global AI markets |

| Space Economy | Limited governance on resource extraction and debris management beyond Earth |

| Bioeconomy Standards | Synthetic biology raises novel questions about ownership and organism movement |

| Climate Adaptation Finance | Developing countries need trillions but allocation mechanisms remain incomplete |

| Geoeconomic Competition | Subsidy races in semiconductors and batteries exceed $500 billion without WTO disciplines |