Table of Contents

God and the Human Mind: An Introduction to Scientific Curiosity

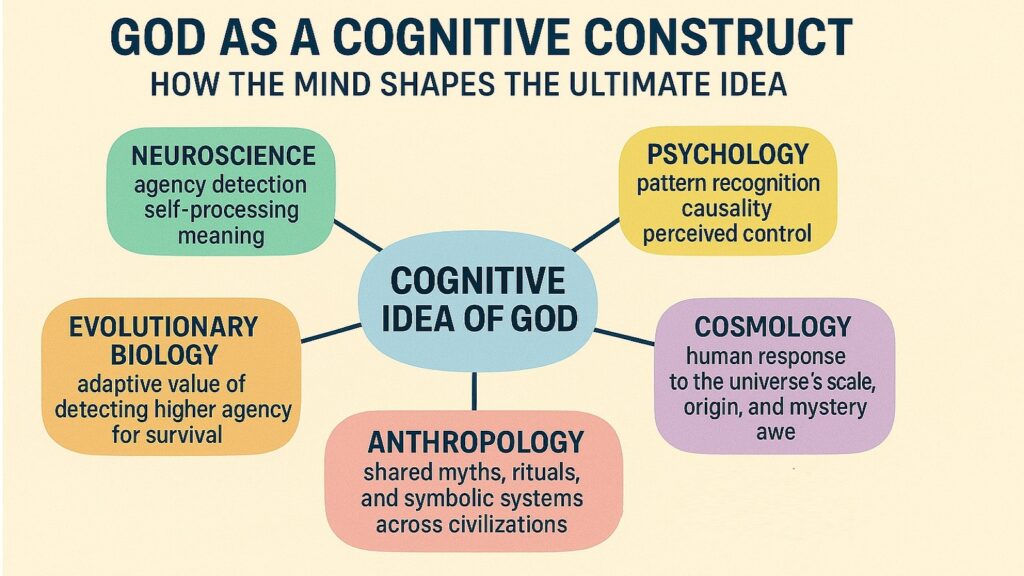

Every culture across human history has formed ideas about God. From ancient Mesopotamia to modern metropolises, the concept appears again and again. This pattern raises a fascinating question for science: Why does the human mind naturally construct notions of higher powers? The answer lies not in theology or debate about existence, but in understanding how our brains work.

This exploration uses neuroscience, psychology, anthropology, and evolutionary biology to examine God as a cognitive phenomenon. The word God here refers to the universal idea that emerges from human thought and culture. It represents how we process the world around us, not the doctrines of specific religions. Scientists study this concept the way they study language, music, or art—as something distinctly human that reveals truths about our minds.

The brain creates models of reality. It seeks patterns, assigns meaning, and builds narratives. When early humans looked at lightning or heard thunder, their minds searched for causes. When they gazed at stars or felt awe before mountains, their consciousness responded in specific ways. These responses, repeated across millennia and continents, shaped how civilizations imagined forces beyond themselves.

Understanding God through science does not diminish personal faith or spirituality. Rather, it adds another lens through which we can appreciate the remarkable architecture of human consciousness. The scientific perspective complements other ways of knowing. It shows us that certain cognitive features unite all people, regardless of where or when they lived.

Scientific Disciplines That Study the God Concept

| Discipline | Focus Area |

|---|---|

| Neuroscience | Brain regions activated during religious experiences and transcendent states |

| Evolutionary Psychology | How belief systems enhanced survival and group cooperation in early humans |

| Anthropology | Universal patterns of God concepts across diverse cultures and time periods |

| Cognitive Science | Mental processes involved in attributing agency and detecting patterns |

| Social Psychology | How belief in higher powers affects community bonding and moral behavior |

| Cosmology | Human responses to vastness, deep time, and existential questions about origins |

1. God and Human Pattern-Seeking: Why the Brain Detects Meaning Everywhere

The human brain evolved to find patterns. This ability kept our ancestors alive. A rustling in tall grass might mean wind, or it might mean a predator. Those who assumed agency—who thought something caused the movement—survived more often. This tendency, called hyperactive agency detection, remains wired into modern minds.

Pareidolia describes how we see faces in clouds or hear voices in the wind. The brain takes incomplete information and fills gaps with familiar shapes. Ancient people applied this same process to natural phenomena. Storms became angry gods. Sunshine became divine favor. Droughts meant displeasure from above. The pattern-seeking mind transformed random events into purposeful actions.

Predictive processing theory explains that brains constantly generate hypotheses about what comes next. We use past experiences to predict future events. When something unexpected happens, the mind searches for explanations. Early humans lacked scientific frameworks to explain earthquakes, eclipses, or disease outbreaks. The brain’s natural response was to attribute these events to intentional beings with greater power.

This cognitive tendency appears universal. Studies using brain imaging show that specific neural networks get activated when people detect patterns or assign agency. The temporoparietal junction and medial prefrontal cortex light up during these processes. These regions help us understand the intentions and predict the behaviors of others. When extended beyond visible agents, they create space for imagining unseen powers.

The preference for meaningful causes over randomness runs deep. Research shows people feel more comfortable believing events happen for reasons rather than by chance. A child’s illness becomes a test. A narrow escape becomes divine intervention. The mind resists accepting that randomness governs important outcomes. This resistance to chaos likely contributed to early God concepts that provided order and explanation.

Pattern recognition served crucial functions. It helped humans predict seasons, navigate by stars, and understand animal behavior. But this powerful tool also generated beliefs in supernatural agency. The same circuits that let us read social cues and anticipate threats also made us prone to seeing intention where none existed. God’s ideas emerged partly from this fundamental feature of cognition.

Pattern Recognition and Belief Formation

| Cognitive Mechanism | Function in Survival | Role in God Concepts |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperactive Agency Detection | Identified potential threats in environment even with limited information | Led humans to attribute natural events to intentional supernatural agents |

| Pareidolia | Quickly recognized important patterns like faces and familiar objects | Created perception of divine presence in natural formations and phenomena |

| Predictive Processing | Anticipated future events based on past experiences and patterns | Generated expectations of divine intervention and cosmic order |

| Causal Attribution | Explained why events occurred to learn and adapt behavior | Assigned natural disasters and fortune to actions of higher powers |

| Preference for Meaning | Maintained psychological stability by finding purpose in experiences | Transformed random events into meaningful divine communication or tests |

| Social Cognition Networks | Understood intentions and emotions of other people in groups | Extended to imagine emotions and intentions of invisible cosmic beings |

2. God and the Neuroscience of Awe: How the Brain Responds to the Cosmos

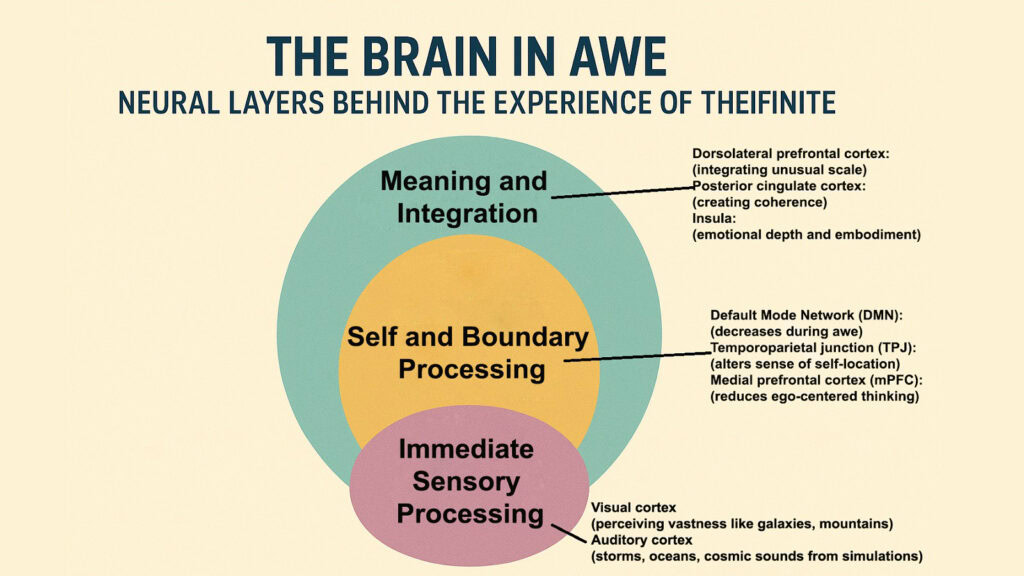

Awe represents a unique emotional state. It arises when encountering something vast that challenges our mental frameworks. Standing beneath a starry sky, viewing the Grand Canyon, or contemplating deep time—these experiences trigger specific brain responses. Neuroscience shows that awe physically alters how we perceive ourselves and the world.

Research by psychologist Dacher Keltner and others reveals that awe activates the prefrontal cortex while quieting the default mode network. The default mode network handles self-referential thinking—our constant internal narrative about “me” and “mine.” When awe reduces this network’s activity, people report feeling smaller, less focused on personal concerns, and more connected to something larger.

Brain imaging studies show that experiencing awe increases activity in regions associated with reward, attention, and processing of complex stimuli. The anterior cingulate cortex, which helps regulate emotions and make meaning, becomes more engaged. These neural changes correlate with reports of transcendence, unity, and connection to forces beyond individual existence.

Early humans experienced awe regularly. They watched lightning split the sky. They witnessed total solar eclipses. They stood beneath auroras dancing across polar nights. Without scientific explanations, these overwhelming experiences demanded interpretation. The brain’s response to vastness—the feeling of encountering something greater—naturally led to concepts of higher powers or divine presence.

Modern research confirms that awe experiences increase belief in supernatural explanations. When people feel small before cosmic vastness, they become more likely to embrace ideas about God or universal consciousness. This correlation appears across cultures and belief systems. The neurological state of awe seems to prepare the mind for transcendent thinking.

The connection between awe and God concepts makes evolutionary sense. Awe experiences often occurred during significant events—eclipses that predicted seasons, storms that brought needed rain, or migrations of animals that meant food. Associating these moments with higher powers created frameworks for understanding and preparing for them. The emotional intensity of awe also strengthened memory, ensuring important patterns got remembered and transmitted.

Neuroscience of Awe and Transcendent Experience

| Brain Region or Network | Normal Function | Changes During Awe |

|---|---|---|

| Default Mode Network | Maintains self-referential thought and personal narrative generation | Reduced activity leading to decreased sense of separate self |

| Prefrontal Cortex | Handles complex thinking, planning, and meaning-making processes | Increased activation during processing of vast or overwhelming stimuli |

| Anterior Cingulate Cortex | Regulates emotional responses and helps assign significance to events | Enhanced engagement when encountering experiences that challenge worldviews |

| Reward Processing Areas | Responds to pleasurable or significant stimuli with dopamine release | Activated during awe, creating positive associations with transcendent moments |

| Visual Processing Centers | Analyzes spatial information and perceives scale of environment | Heightened activity when confronting vastness like starry skies or mountains |

| Temporal Lobe Regions | Involved in memory formation and emotional experiences | Shows increased activity during mystical experiences and religious contemplation |

3. God and Evolutionary Psychology: How Belief Enhanced Early Human Survival

Human evolution favored groups over isolated individuals. Cooperation determined which communities thrived and which perished. Evolutionary psychologists have identified belief systems, including God concepts, as powerful tools that strengthened group cohesion. These beliefs were not evolutionary accidents but features that provided real advantages.

Shared beliefs in higher powers created common ground. When a community believed the same God watched over them, members felt connected through invisible bonds. This shared framework reduced conflict over resources and increased willingness to help strangers within the group. Research shows that people who believe others share their moral foundations trust them more readily.

Costly signaling theory explains how religious practices demonstrate commitment to the group. Fasting, pilgrimages, and rituals required sacrifice. These acts signaled that individuals valued the community enough to pay personal costs. Groups whose members displayed such commitment functioned more efficiently. They could coordinate large projects and mount stronger defenses against threats.

Belief in observing deities also affected behavior. Studies demonstrate that people act more cooperatively when they believe supernatural agents watch them. Even subtle religious primes—like images of eyes or words related to God—increase prosocial behavior in experiments. Early humans who believed Gods monitored their actions likely treated each other more fairly, strengthening community bonds.

Anxiety reduction represents another evolutionary advantage. The human brain, with its capacity for abstract thought, can imagine countless threats. Worry about death, disease, or disaster could paralyze action. Beliefs in protective higher powers helped regulate this anxiety. When people trusted that Gods controlled outcomes, they could function despite uncertainty.

Mortality management theory, developed by researchers studying mortality awareness, shows that belief systems help humans cope with knowledge of their own death. This unique awareness creates existential dread that must be managed. God concepts provided frameworks that made death comprehensible and less terrifying. Communities with effective anxiety-reduction mechanisms likely outperformed those without them.

Evolutionary Advantages of Belief Systems

| Evolutionary Pressure | Survival Challenge | How God Concepts Helped |

|---|---|---|

| Group Cohesion | Maintaining cooperation among genetically unrelated individuals | Shared beliefs created common identity and reduced internal conflict |

| Trust Among Strangers | Coordinating with community members outside family units | Belief in same higher power signaled shared values and moral codes |

| Resource Management | Distributing limited food, water, and shelter fairly | Divine commandments provided accepted rules that reduced disputes |

| Anxiety Regulation | Managing fear of death, disease, and uncertain future | Trust in protective deities reduced paralyzing existential dread |

| Costly Signaling | Identifying committed versus opportunistic group members | Religious practices required sacrifice that proved genuine group loyalty |

| Moral Enforcement | Ensuring cooperation even when not being watched by others | Belief in observing Gods increased prosocial behavior and fairness |

4. God and Anthropological Universality: Why Every Civilization Imagined a Higher Power

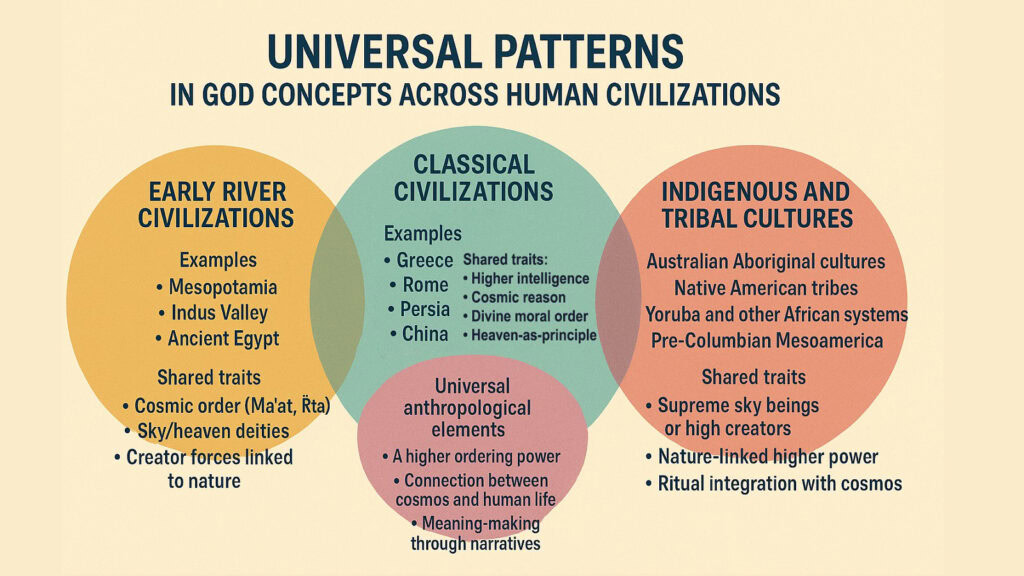

Archaeological evidence reveals that God concepts emerged independently across continents. Ancient Sumerians wrote about An and Enlil. Egyptians worshipped Ra and Osiris. The Indus Valley civilization left seals suggesting reverence for divine figures. Mesoamerican cultures developed pantheons without contact with Old World religions. Indigenous Australian peoples maintained dreamtime narratives for tens of thousands of years.

This universality suggests something fundamental about human cognition rather than cultural borrowing. Anthropologists note that while specific beliefs vary enormously, the underlying pattern—imagining powers beyond human control—appears everywhere. Even societies separated by oceans and millennia developed similar frameworks for understanding their place in the cosmos.

The archaeological record shows God concepts dating back at least forty thousand years. Cave paintings, burial practices with grave goods, and carved figurines all point to beliefs in existence beyond death and forces beyond visibility. These practices required significant effort and resources, indicating that such beliefs held deep importance for ancient communities.

Comparative mythology reveals striking parallels. Creation stories often involve emergence from chaos or the void. Flood narratives appear across cultures from Mesopotamia to the Americas. Sky gods and earth mothers recur in distant regions. These similarities likely reflect universal human experiences—everyone witnesses storms, depends on earth’s fertility, and wonders about origins.

Anthropologist Pascal Boyer argues that God concepts succeed because they violate intuitive physics in minimal, memorable ways. A god who knows everything violates normal information constraints but remains person-like in other respects. These counterintuitive elements make the concept sticky—easy to remember and transmit. Purely ordinary concepts or completely bizarre ones spread less effectively.

The persistence of God’s ideas across cultural evolution demonstrates their adaptive value. Societies that developed cohesive belief systems could coordinate larger projects, from irrigation systems to defensive walls. They could maintain order across growing populations. The archaeological record shows that complex civilizations consistently developed organized religious structures alongside other institutions.

God Concepts Across Ancient Civilizations

| Civilization | Time Period | Key Features of God Concepts |

|---|---|---|

| Sumerian (Mesopotamia) | 4500-1900 BCE | Pantheon of nature deities controlling storms, fertility, and cosmic order |

| Ancient Egyptian | 3100-30 BCE | Gods associated with sun, death, and afterlife; pharaohs as divine intermediaries |

| Indus Valley | 3300-1300 BCE | Possible proto-Shiva figures and mother goddess representations in artifacts |

| Ancient Greek | 800-146 BCE | Anthropomorphic gods with human emotions governing natural and social domains |

| Mesoamerican (Maya, Aztec) | 2000 BCE-1500 CE | Complex calendrical deities linked to agricultural cycles and cosmic forces |

| Indigenous Australian | 65000 BCE-present | Dreamtime beings who shaped landscape and established social laws |

5. God and the Theory of Mind: How Humans Imagine Conscious Intent Beyond Themselves

Theory of mind represents a crucial cognitive ability. It lets us understand that other people have thoughts, feelings, and intentions different from our own. This capacity typically develops in children around age four. Without it, social interaction becomes nearly impossible. We constantly use the theory of mind to predict what others will do, feel empathy, and navigate complex relationships.

Humans appear unique in the extent of this ability. While some primates show a rudimentary theory of mind, humans take it much further. We can imagine what someone else thinks about a third person’s beliefs—a level of complexity that requires sophisticated neural machinery. The medial prefrontal cortex, temporoparietal junction, and precuneus all contribute to these mental simulations.

Importantly, the theory of mind does not limit itself to visible agents. Once the brain develops this capacity, it can project intentionality onto anything. Children talk to stuffed animals as if they have desires. Adults address pets as if they understand complex language. This tendency to over-attribute mind and agency extends naturally to invisible forces.

Psychologist Justin Barrett coined the term “hypersensitive agency detection device” to describe how readily humans perceive intentional agents. Research shows that even adults see purposeful action in simple geometric shapes moving on screens if the movement suggests goal-directedness. This hair-trigger agency detection helped ancestors avoid predators but also made them prone to imagining conscious beings in natural processes.

God concepts represent an extension of the theory of mind beyond its original scope. Early humans experienced events—storms, illness, fortune—that demanded explanation. The cognitive tools available for making sense of the world involved understanding intentions and emotions. Applying these tools to natural phenomena naturally produced ideas of conscious agents behind them.

Developmental psychology shows that children readily adopt God concepts. Studies across cultures find that young children attribute broad knowledge and power to divine figures more easily than adults. Their developing theory of mind naturally accommodates beliefs in minds that differ from human limitations. This developmental pattern suggests that God concepts align well with how young brains process agency and intention.

Theory of Mind and Divine Agency

| Cognitive Capacity | Typical Human Use | Extension to God Concepts |

|---|---|---|

| Intention Attribution | Understanding that others act based on goals and desires | Assigning purposeful intent to natural events and cosmic patterns |

| Belief-Desire Psychology | Predicting behavior based on what others know and want | Imagining divine plans, wishes, and knowledge beyond human limits |

| Emotional Recognition | Identifying and responding to feelings in other people | Attributing emotions like anger, love, or mercy to higher powers |

| Perspective Taking | Seeing situations from another person’s viewpoint | Contemplating divine perspective on human actions and morality |

| Mental State Reasoning | Tracking what different people know versus what is hidden | Conceiving omniscient beings who know hidden thoughts and future events |

| Social Relationship Models | Maintaining complex networks of obligations and alliances | Developing personal relationships with deities through prayer and devotion |

6. God and the Need for Meaning: Why Humans Seek Purpose in a Vast Universe

Humans create narratives. We structure experience into stories with beginnings, middles, and ends. This narrative capacity helps us learn from the past and plan for the future. But it also generates existential questions. Why are we here? What is our purpose? Does existence have direction or significance? These questions arise naturally from a brain built to find patterns and meanings.

Cognitive science shows that meaning-making serves psychological functions. Studies demonstrate that people with a strong sense of purpose experience better mental health and physical wellbeing. Those who see their lives as meaningful report less anxiety and depression. The brain appears to need coherent frameworks that organize experience into comprehensible wholes.

God concepts provide powerful meaning-making structures. They answer ultimate questions about origins, purpose, and destiny. They transform individual existence from a random occurrence into a part of a larger design. Viktor Frankl, who studied meaning and survival, noted that people endure tremendous suffering when they believe it serves some purpose. Belief systems that frame hardship as meaningful help people persevere.

The cosmos presents challenges to meaning-making. Space extends billions of light-years. Earth orbits an ordinary star in an unremarkable galaxy. Human existence occupies a vanishingly brief moment in cosmic time. These facts can make an individual’s life feel insignificant. God concepts counteract this by asserting that human existence matters within a larger framework.

Psychological research on meaning identifies several sources: connection to others, contribution to something beyond self, comprehension of one’s life, and coherence between beliefs and actions. Religious and spiritual frameworks address all these elements simultaneously. They connect individuals to communities, provide missions that transcend personal gain, offer explanatory narratives, and establish moral codes that guide behavior.

Mortality management theory demonstrates that when reminded of mortality, people cling more tightly to meaning-making systems. This suggests that God concepts help manage the anxiety generated by awareness of death. Unlike other animals, humans know they will die. This knowledge creates a psychological burden that requires management. Beliefs in the afterlife, cosmic justice, or transcendent purpose ease this burden.

Psychological Functions of Meaning-Making

| Human Need | Psychological Challenge | How God Concepts Address It |

|---|---|---|

| Existential Coherence | Making sense of why we exist and what life is for | Provide origin stories and cosmic purpose for human existence |

| Mortality Management | Coping with awareness of inevitable death | Offer frameworks for afterlife, legacy, or transcendence beyond death |

| Suffering Explanation | Finding reason for pain, loss, and hardship | Frame difficulties as tests, growth opportunities, or part of divine plan |

| Cosmic Significance | Feeling meaningful in vast, impersonal universe | Assert that human consciousness and choices matter to higher powers |

| Moral Framework | Determining right and wrong without arbitrary rules | Establish ethical codes grounded in divine will or cosmic order |

| Community Connection | Finding belonging and shared purpose with others | Create bonds through common beliefs, rituals, and collective identity |

God and the Human Journey: A Conclusion Grounded in Science and Wonder

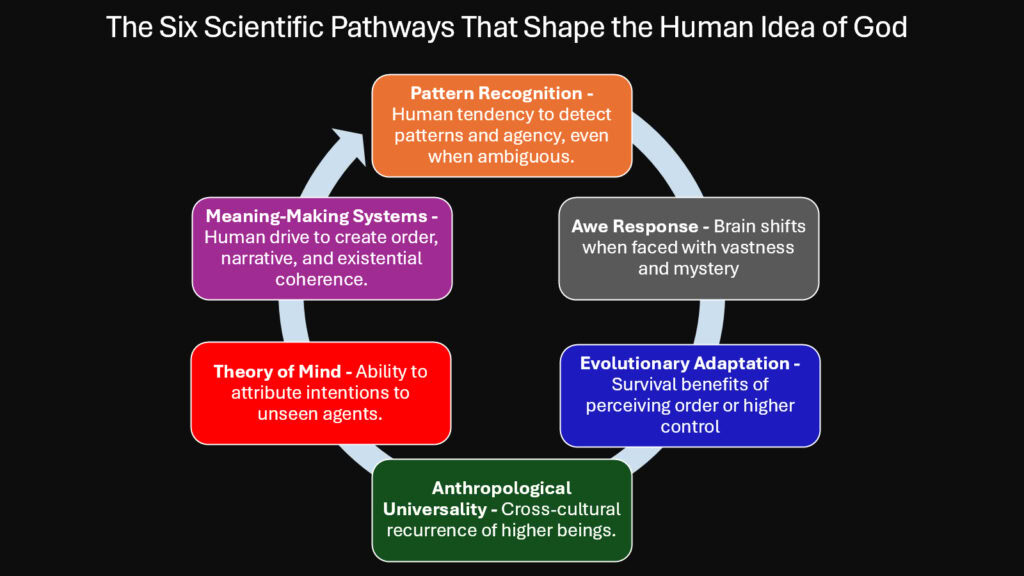

Six scientific insights illuminate why the God concept appears universally across human cultures. Pattern recognition makes minds interpret events as intentional actions. Awe responses to vastness naturally produce thoughts of transcendence. Evolutionary pressures favored groups with shared beliefs that enhanced cooperation. Anthropological evidence shows independent emergence of higher power concepts across continents.

These insights do not prove or disprove God’s existence. They reveal something equally profound: that human minds are structured in ways that naturally generate ideas about higher powers. This universal tendency reflects cognitive architecture shared by all people. It connects ancient cave painters to modern city dwellers through fundamental features of consciousness.

The human journey continues. We probe the origins of the cosmos with telescopes and particle accelerators. We map the brain with unprecedented precision. We uncover the deep history of our species through genetics and archaeology. Each discovery adds layers to our self-understanding. Studying why humans imagine God reveals as much about consciousness as about belief. It shows us what we are: meaning-seeking, pattern-finding, awe-capable beings trying to comprehend our place in a vast cosmos.

Integration of Scientific Perspectives on God

| Scientific Lens | Central Question | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroscience | How does the brain generate religious experiences? | Specific neural networks create sense of transcendence and connection to something greater |

| Evolutionary Psychology | Why did belief systems persist across human evolution? | Shared beliefs enhanced group cooperation, reduced anxiety, and improved survival outcomes |

| Anthropology | Why do God concepts appear in all human societies? | Universal cognitive architecture generates similar frameworks for understanding existence |

| Cognitive Science | What mental processes create ideas about divine agency? | Pattern recognition and theory of mind naturally extend to imagining supernatural agents |

| Developmental Psychology | How do children acquire beliefs about higher powers? | Young minds readily accept God concepts through same processes that develop social cognition |

| Existential Psychology | What functions do beliefs about God serve for individuals? | Provide meaning, reduce death anxiety, and create coherent narratives about life purpose |

Read More Science Related Articles

- Anthropomorphism: 6 Brilliant Benefits and Risks in AI

- AI and Consciousness: 8 Exciting Concepts Driving Research

- Black Hole Singularity: 6 Mind-Blowing Truths Explained

- 6 Incredible Ways Missiles Obey The Laws of Physics

- Millisecond Pulsars: 6 Incredible Insights Driving Science

- Human Cell Secrets: 6 Powerful Insights Shaping Life

Disclaimer: This article explores the concept of God through scientific disciplines such as neuroscience, psychology, anthropology, cosmology, and evolutionary biology. It does not seek to question, disprove, or challenge any religious belief. The discussion focuses on cognitive and cultural perspectives without taking a position on God’s existence or promoting any religious or non-religious viewpoint. It is intended to provide a respectful, science-based analysis that acknowledges and honors diverse faiths and worldviews. The article does not intend to hurt anyone’s religious or spiritual sentiments.