Table of Contents

Introduction: In Medias Res and the Art of Falling Into Story

The renowned Roman poet Horace once recommended that writers dive directly into the core of the action. He called this technique In Medias Res, meaning “into the middle of things.” This storytelling technique doesn’t just begin a narrative in the middle—it creates an emotional freefall that rewires how we experience stories. When Homer opened The Odyssey with Odysseus stranded on Calypso’s island rather than departing from Troy, he established one of literature’s most powerful techniques.

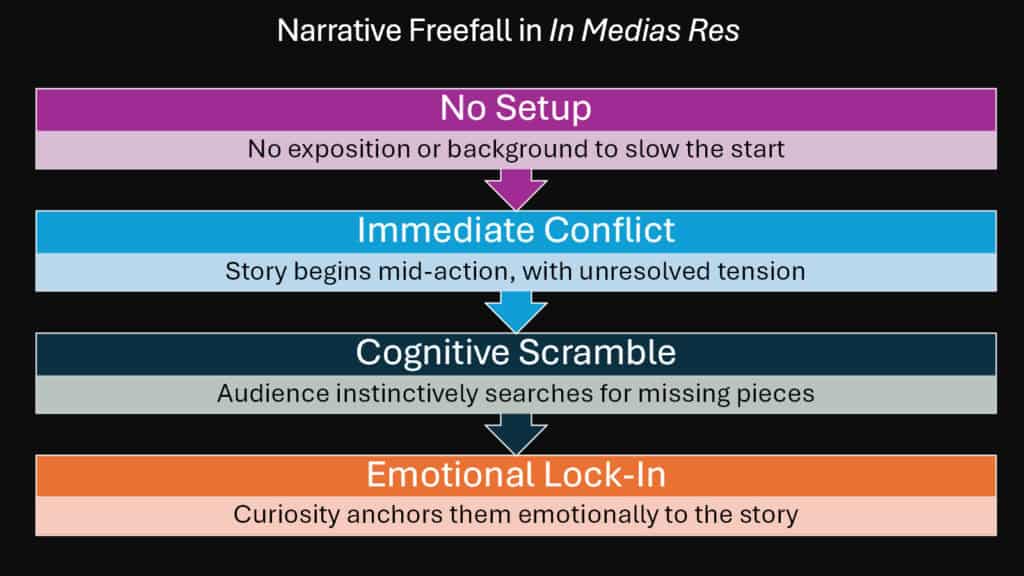

In Medias Res functions like a narrative trapdoor. Readers find themselves dropped into unfamiliar territory without warning or preparation. The technique abandons traditional exposition and throws audiences directly into crisis, conflict, or climactic moments. This approach fundamentally alters narrative gravity—the invisible force that pulls readers through a story’s progression.

Unlike conventional storytelling that builds momentum gradually, In Medias Res begins with maximum velocity. Readers must scramble to understand context while experiencing immediate emotional impact. This disorientation becomes a gravitational pull that keeps audiences anchored to the narrative. The technique appears across global literature, from ancient Sanskrit epics to contemporary African novels, proving its universal appeal and effectiveness.

The six ways In Medias Res rewires narrative gravity include triggering curiosity gaps, fracturing traditional time structures, creating new gravitational centers, delivering emotional shockwaves, deepening immersion through disorientation, and reshaping endings through return loops. Each method transforms how stories exert their pull on readers, making them more urgent, memorable, and emotionally resonant.

Understanding In Medias Res reveals why certain stories feel impossible to abandon while others struggle to maintain reader interest. This technique doesn’t merely rearrange narrative elements—it fundamentally changes the physics of storytelling itself.

| Classic In Medias Res Examples Across Cultures | Opening Context | Cultural Origin |

|---|---|---|

| The Odyssey (Homer) | Odysseus trapped on Calypso’s island | Ancient Greece |

| Ramayana (Valmiki) | Rama in exile, kingdom in turmoil | Ancient India |

| Things Fall Apart (Achebe) | Okonkwo’s established reputation and fear | Nigeria |

| One Hundred Years of Solitude (Márquez) | Colonel Aureliano facing firing squad | Colombia |

| The Tale of Genji (Murasaki) | Genji’s established court relationships | Japan |

1. In Medias Res and the Curiosity Gap That Pulls Us In

George Loewenstein’s Information Gap Theory explains why humans feel compelled to seek missing information. When we recognize a gap between what we know and what we want to know, curiosity becomes an almost physical force. In Medias Res weaponizes this psychological mechanism by deliberately withholding crucial backstory while presenting compelling present-moment drama.

Consider the opening of One Hundred Years of Solitude by García Márquez: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” This sentence creates multiple curiosity gaps simultaneously. Why is the colonel facing execution? What led to this moment? How does discovering ice connect to his current predicament?

The technique forces readers to become active investigators rather than passive recipients. Traditional storytelling provides context before conflict, but In Medias Res reverses this order. Readers must piece together background information while experiencing immediate dramatic tension. This cognitive juggling act creates what Loewenstein describes as the “itch” of curiosity—an uncomfortable mental state that demands resolution.

African literature demonstrates this principle powerfully. Chinua Achebe begins Things Fall Apart by establishing Okonkwo’s reputation and fears without explaining their origins. Readers immediately understand that this man’s strength masks deep anxieties, but the specific sources remain mysterious. This gap drives readers forward, seeking the experiences that shaped Okonkwo’s character.

Japanese literature employs similar techniques. Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji commences with the main character already situated at court, with his relationships and reputation firmly established. The reader enters an ongoing story, compelled to understand the complex web of connections that preceded this moment.

In Medias Res transforms curiosity from a gentle pull into gravitational force. The technique creates information vacuums that readers feel compelled to fill, ensuring continued engagement with the narrative.

| Information Gap Theory Applied to In Medias Res | Gap Type | Reader Response |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Gap | Missing backstory | Seeks character history |

| Causal Gap | Unexplained circumstances | Searches for cause-effect relationships |

| Emotional Gap | Unclear motivations | Investigates character psychology |

| Contextual Gap | Unknown setting details | Reconstructs world-building elements |

| Relational Gap | Unexplained connections | Maps character relationships |

2. In Medias Res and the Fracture of Traditional Time

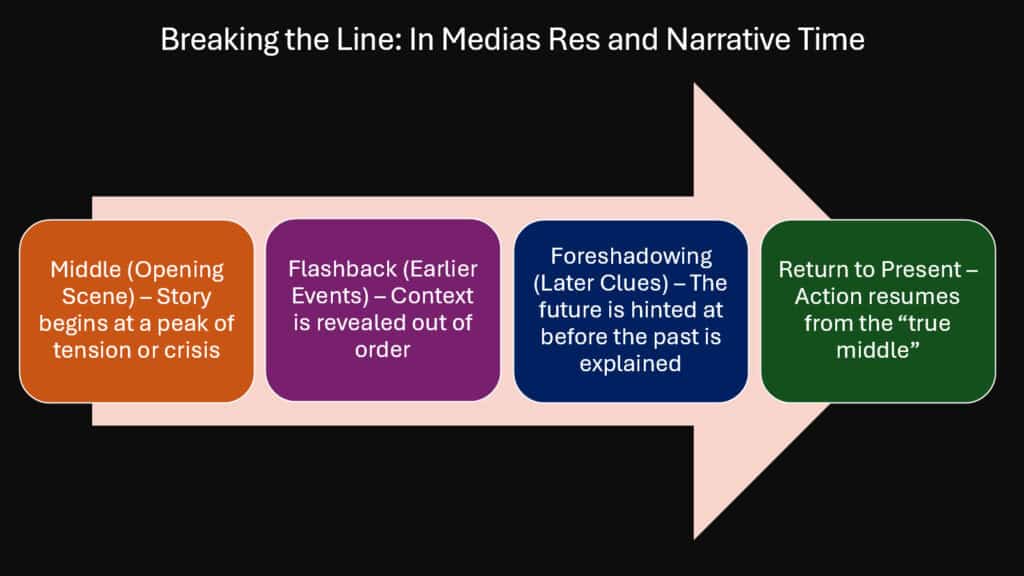

Traditional narratives follow chronological progression—beginning, middle, end—like travelers walking down a straight road. In Medias Res shatters this linear expectation, creating temporal fragments that readers must reassemble. This fracturing doesn’t merely rearrange events; it fundamentally alters how time feels within the narrative space.

Latin American literature exemplifies this temporal disruption. Isabel Allende’s The House of the Spirits begins with Clara’s prophetic abilities already established, then loops backward to reveal how she developed these powers. The narrative moves like a spiral rather than a line, circling back to illuminate earlier mysteries while pushing forward toward resolution.

Chinese literature employs similar techniques with different cultural resonances. Journey to the West begins with the Monkey King already possessing supernatural abilities, then reveals through flashbacks how he acquired his powers. This structure mirrors traditional Chinese storytelling, where the present moment contains echoes of past actions and future consequences.

European literature demonstrates the technique’s adaptability across cultural contexts. James Joyce’s Ulysses drops readers into Leopold Bloom’s day without preamble, forcing them to construct his character through accumulated moments rather than explicit exposition. The narrative refuses to explain itself, demanding active participation from readers.

Indigenous Australian storytelling traditions have long employed non-linear temporal structures. Contemporary Aboriginal authors like Alexis Wright use In Medias Res to reflect traditional Dreamtime narratives, where past, present, and future exist simultaneously rather than sequentially.

This temporal fracturing creates what theorists call “narrative archaeology.” Readers must excavate meaning from scattered fragments, reconstructing cause-and-effect relationships that traditional storytelling presents directly. The technique transforms reading from passive consumption into active construction, making readers collaborators in creating meaning.

| Temporal Disruption Techniques in Global Literature | Cultural Context | Narrative Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Spiral Structure | Latin American magical realism | Past and present interweave |

| Circular Time | Chinese classical literature | Events echo across time periods |

| Stream of Consciousness | European modernism | Mind’s non-linear processing |

| Dreamtime Narrative | Aboriginal Australian | All time exists simultaneously |

| Episodic Revelation | Indian epic tradition | Truth emerges through fragments |

3. In Medias Res and the Narrative Center of Gravity

Tzvetan Todorov’s structural analysis reveals that traditional narratives organize around equilibrium, disruption, and restoration. In Medias Res relocates this organizational center, often anchoring stories in crisis, trauma, or turning points rather than peaceful beginnings. This redistribution fundamentally changes how narrative weight gets distributed throughout the story.

Consider the structural differences between conventional and In Medias Res approaches. Traditional stories build toward climactic moments, accumulating dramatic weight gradually. In Medias Res begins with maximum dramatic intensity, then reveals the foundations that support this heightened state. The technique creates what structuralists call “inverted pyramids”—stories that begin at their widest dramatic point and narrow toward explanatory resolution.

Indian epic literature demonstrates this principle through the Mahabharata. The narrative begins with the great war already a certainty, the opposing armies assembled on Kurukshetra. Rather than building toward this conflict, the epic explores the complex relationships and moral dilemmas that made war inevitable. The gravitational center lies not in the future battle but in the present moment of choice.

African oral traditions employ similar structural inversions. Traditional praise poetry begins with the greatest accomplishment of a hero, then circles back to reveal the journey that made such an achievement possible. This structure reflects the cultural understanding that a person’s essence is best revealed through their defining moments rather than their origins.

European drama adapted this principle through techniques like the “German scene.” Playwrights would begin with characters in the midst of emotional crisis, then gradually reveal the circumstances that created such intensity. This approach concentrated dramatic energy at the narrative’s beginning rather than its climax.

The structural implications extend beyond individual scenes to entire narrative architectures. In Medias Res creates stories that feel top-heavy with meaning, requiring readers to provide gravitational balance through their interpretive engagement.

| Structural Analysis: Traditional vs. In Medias Res | Traditional Structure | In Medias Res Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Opening | Equilibrium/Peace | Crisis/Disruption |

| Development | Building tension | Revealing foundation |

| Climax | Maximum intensity | Understanding/Recognition |

| Resolution | Return to equilibrium | New equilibrium based on knowledge |

| Reader Role | Passive observer | Active interpreter |

4. In Medias Res and the Emotional Shockwave of Instant Action

When audiences encounter immediate conflict without preparation, their emotional engagement spikes dramatically. In Medias Res bypasses the traditional warming-up period, delivering what psychologists call “acute emotional activation.” This technique simulates real-life crisis experiences, where understanding follows rather than precedes emotional response.

Human brains process threatening or intense situations through the amygdala before higher cognitive functions engage. In Medias Res exploits this neurological sequence by presenting dramatic scenarios that trigger immediate emotional response while cognitive understanding remains incomplete. Readers feel first and understand second, mirroring how people actually experience crisis.

Brazilian literature demonstrates this principle through works like Jorge Amado’s novels, which often begin in the middle of passionate conflicts or celebrations. Readers find themselves emotionally engaged with characters before understanding their backgrounds or motivations. This emotional anchoring creates powerful connections that pure exposition cannot achieve.

Korean literature employs similar techniques through traditional pansori storytelling, which begins with the most emotionally intense moment of a character’s journey. Modern Korean writers such as Han Kang employ In Medias Res to establish an immediate connection with characters undergoing trauma or transformation.

Russian literature has long understood the power of emotional immediacy. Dostoyevsky frequently begins novels with characters in states of extreme psychological tension, forcing readers to experience their mental turmoil before understanding its sources. This technique creates empathy through shared disorientation rather than explained sympathy.

The emotional shockwave effect works because it mirrors authentic human experience. People rarely encounter life-changing events with complete preparation or understanding. In Medias Res replicates this authenticity, making fictional experiences feel more real than carefully explained narratives.

| Emotional Engagement Patterns in In Medias Res | Immediate Response | Delayed Understanding |

|---|---|---|

| Character Crisis | Empathetic concern | Causal comprehension |

| Action Sequences | Adrenaline response | Strategic analysis |

| Relationship Conflicts | Emotional investment | Relationship history |

| Moral Dilemmas | Instinctive judgment | Ethical complexity |

| Transformative Moments | Vicarious experience | Personal significance |

5. In Medias Res and the Disorientation That Deepens Immersion

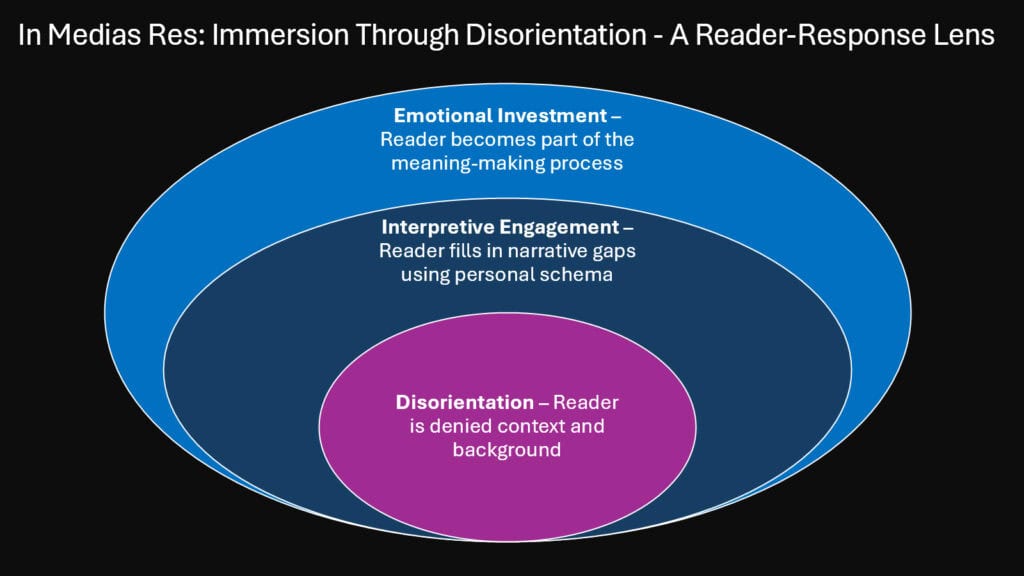

Stanley Fish’s Reader-Response Theory suggests that readers actively create meaning through their interpretive engagement with texts. In Medias Res amplifies this co-creative process by forcing readers to construct context from incomplete information. Paradoxically, this disorientation can deepen rather than diminish immersion, as readers become more actively involved in meaning-making.

When readers encounter unfamiliar narrative territory, they must draw upon their own experiences and knowledge to fill gaps. This process creates what Fish calls “interpretive communities”—shared approaches to understanding textual ambiguity. In Medias Res transforms readers from passive consumers into active collaborators, making them stakeholders in the narrative’s success.

Scandinavian literature demonstrates this principle through works like Knut Hamsun’s novels, which often begin with characters in states of psychological confusion or physical displacement. Readers must work alongside protagonists to understand their circumstances, creating shared experiences of discovery and recognition.

Middle Eastern literature employs similar techniques through traditional maqamat forms, which begin in the middle of elaborate scenarios requiring reader interpretation. Contemporary authors like Nawal El Saadawi use In Medias Res to challenge readers’ assumptions about character motivations and social contexts.

Canadian literature, particularly Indigenous authors like Thomas King, uses In Medias Res to reflect oral storytelling traditions where audiences are expected to contribute interpretive energy. Readers must engage actively with cultural contexts and narrative assumptions to fully understand the stories.

This interpretive collaboration creates stronger emotional bonds between readers and narratives. When people work to understand something, they become more invested in its outcome. In Medias Res utilizes this psychological concept, allowing readers to feel a sense of partial responsibility for the interpretation of the story’s meaning..

| Reader-Response Theory Applications in In Medias Res | Reader Activity | Narrative Result |

|---|---|---|

| Gap-Filling | Supplying missing context | Increased investment |

| Pattern Recognition | Identifying narrative clues | Enhanced engagement |

| Emotional Projection | Relating to character confusion | Deeper empathy |

| Cultural Translation | Applying personal knowledge | Personalized meaning |

| Collaborative Construction | Working with author intentions | Shared ownership |

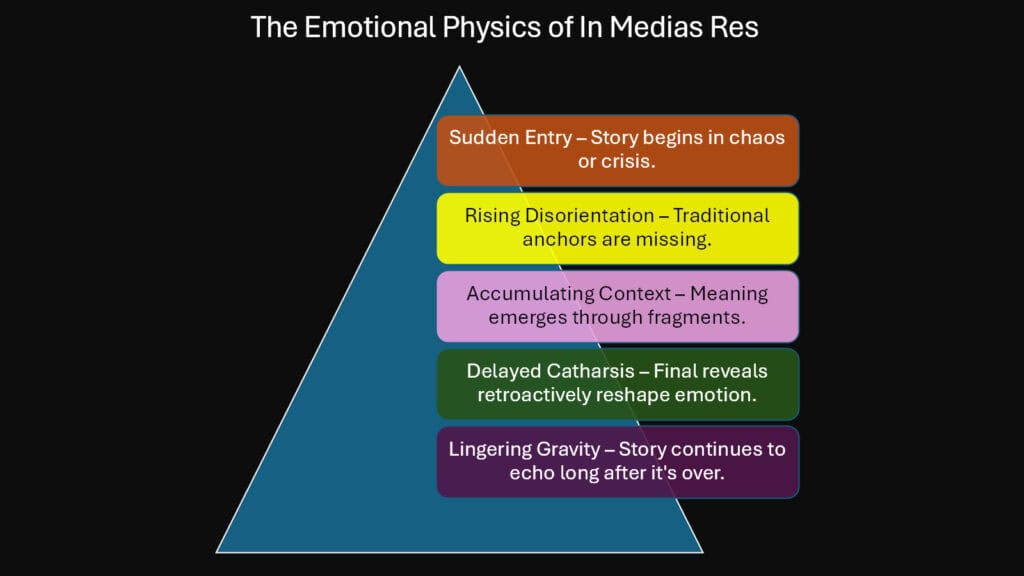

6. In Medias Res and the Return Loop: How Middles Reshape Endings

When stories begin in the middle, they create an obligation to circle back and reveal the hidden beginning. This return loop fundamentally alters how endings function, often creating delayed catharsis and intensifying closure. The technique transforms endings from simple resolutions into complex revelations that recontextualize everything readers thought they understood.

Traditional narratives build toward endings that feel inevitable once reached. In Medias Res creates endings that feel revelatory, providing missing pieces that complete puzzles readers didn’t know they were solving. This difference changes the emotional texture of closure from satisfaction to recognition.

Mexican literature exemplifies this principle through works like Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo, which begins with the protagonist’s journey to find his father, then gradually reveals that both the journey and the father exist in realms beyond conventional reality. The ending doesn’t conclude the story so much as illuminate its true nature.

Turkish literature employs similar return loops through authors like Orhan Pamuk, whose novels often begin with mysterious circumstances that only become clear when the narrative circles back to reveal hidden connections. The technique creates what readers experience as “inevitable surprises”—endings that feel both unexpected and perfectly logical.

Australian literature demonstrates the return loop through works like Peter Carey’s novels, which frequently begin with characters in unusual situations that only make sense when their complete histories emerge. The technique reflects the continent’s cultural emphasis on hidden histories and concealed connections.

The return loop effect intensifies because readers have been emotionally invested in characters and situations before understanding their complete contexts. When the hidden beginning finally emerges, it carries the weight of all the emotional engagement that preceded understanding. This delayed revelation creates more powerful catharsis than conventional story structures.

| Return Loop Mechanics in Global Literature | Initial Middle | Revealed Beginning | Transformed Ending |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mystery/Revelation | Character in crisis | Hidden past trauma | Recognition and healing |

| Quest/Discovery | Journey in progress | Forgotten motivation | Fulfilled purpose |

| Relationship/Conflict | Existing tension | Original connection | Renewed understanding |

| Transformation/Growth | Changed character | Catalytic event | Integrated identity |

| Social/Political | Current situation | Historical cause | Broader implications |

Conclusion: In Medias Res and the Gravity That Never Lets Go

The six ways In Medias Res rewires narrative gravity reveal why this ancient technique remains vital in contemporary storytelling. By triggering curiosity gaps, fracturing traditional time, relocating gravitational centers, delivering emotional shockwaves, deepening immersion through disorientation, and creating return loops, the technique fundamentally alters how stories exert their pull on readers.

In Medias Res doesn’t merely rearrange narrative elements—it changes the physics of storytelling itself. Stories that employ this technique fall faster into reader consciousness, pull harder on emotional engagement, and linger longer in memory. The technique creates what might be called “narrative black holes”—stories so dense with immediate meaning that readers cannot escape their gravitational pull.

The global prevalence of In Medias Res across cultures and centuries suggests something fundamental about human psychology and storytelling needs. People seem drawn to narratives that mirror the complexity and non-linearity of actual experience. Life rarely provides exposition before crisis, and In Medias Res acknowledges this reality by creating fictional experiences that feel authentically disorienting and immediately engaging.

Understanding these six mechanisms helps explain why certain stories feel impossible to abandon while others struggle to maintain interest. The technique doesn’t guarantee narrative success, but it creates structural conditions that favor deep reader engagement. When executed skillfully, In Medias Res transforms reading from passive entertainment into active collaboration.

The gravitational metaphor proves apt because gravity is invisible yet undeniable, gentle yet inescapable. In Medias Res creates similar forces within narrative space—subtle influences that profoundly shape reader experience. Starting in the middle may feel chaotic, but chaos often contains the seeds of the most memorable order.

| Cumulative Effects of In Medias Res Techniques | Immediate Impact | Lasting Influence |

|---|---|---|

| Curiosity Gaps | Compulsive reading | Memorable uncertainty |

| Temporal Fracture | Active interpretation | Complex understanding |

| Gravitational Shift | Intense engagement | Structural appreciation |

| Emotional Shockwave | Immediate connection | Authentic empathy |

| Disorienting Immersion | Collaborative meaning-making | Personal investment |

| Return Loops | Delayed catharsis | Recontextualized experience |