Table of Contents

Introduction: How the Graphic Narrative Quietly Shatters Us

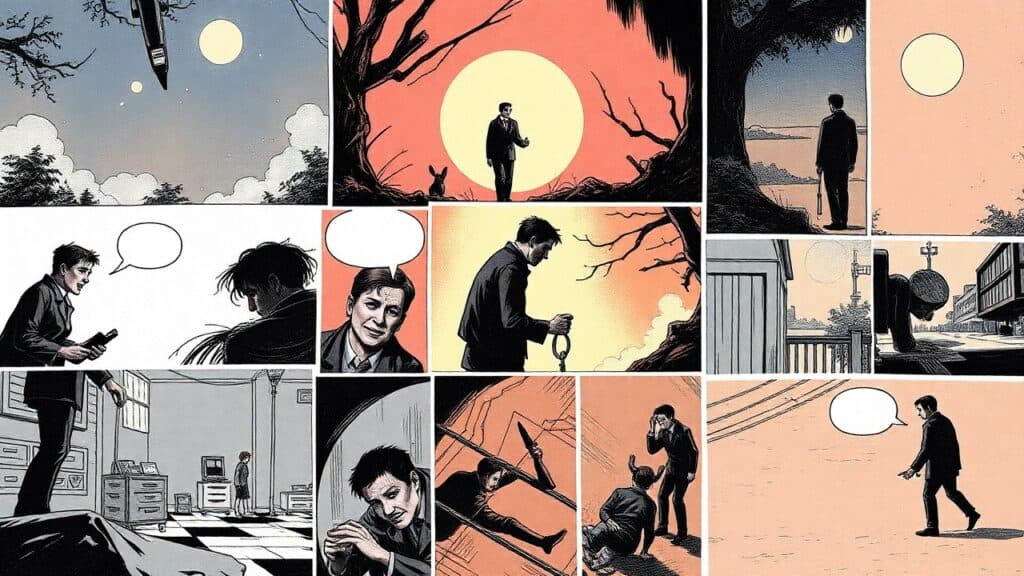

In the quiet corners of bookstores, graphic narratives wait like patient witnesses. They hold stories that refuse to be told in ordinary ways. Art Spiegelman’s Maus does not shout about the Holocaust—it whispers through mice and cats, through panels that break and reform like memory itself. These visual stories have become one of the most powerful and essential storytelling formats of our time, offering what traditional narratives sometimes cannot: a way to hold trauma without crushing it.

The graphic narrative stands apart from other storytelling forms through its unique marriage of image and text. Where prose builds meaning through words alone, and poetry distills emotion into concentrated language, graphic stories create meaning in the spaces between panels. Unlike oral storytelling that depends on voice and presence, or dramatic scripts that require performance, graphic narratives exist in stillness. They invite readers to move at their own pace through visual landscapes that mirror the fractured nature of traumatic memory.

This visual medium has proven particularly adept at expressing what cannot be easily spoken. Through its combination of sequential art, textual elements, and deliberate use of space, the graphic narrative creates room for silence to breathe. It acknowledges that some experiences resist straightforward narration, requiring instead the kind of fragmented, non-linear approach that graphic storytelling naturally provides.

The six ways explored in this article reveal how graphic narratives transform silence into story, absence into presence, and individual pain into collective understanding. These methods work together to create a storytelling form that honors both the complexity of trauma and the resilience of those who survive it.

| Storytelling Format | Primary Method | Approach to Trauma |

|---|---|---|

| Graphic Narrative | Visual-textual synthesis | Fragmented, spatial |

| Prose | Narrative description | Linear, explanatory |

| Poetry | Concentrated language | Metaphorical, rhythmic |

| Oral Storytelling | Voice and presence | Immediate, communal |

| Dramatic Scripts | Performance-based | Dialogue-driven, temporal |

1. Graphic Narrative as Visual Testimony of Silence

The graphic narrative transforms silence into witness through its ability to document what words cannot capture. Visual memory works differently than linguistic memory—it holds fragments, impressions, and emotional textures that resist translation into language. When trauma occurs, the mind often stores experiences as disconnected images, sounds, and sensations rather than coherent narratives. Graphic narratives honor this fragmented nature of traumatic memory by refusing to impose false coherence on experiences that defy linear understanding.

Cathy Caruth’s trauma theory provides a framework for understanding how graphic narratives function as vessels for untellable stories. According to Caruth, trauma exists in a state of temporal disruption—it is simultaneously too present and impossibly absent, too immediate and forever deferred. This paradox finds perfect expression in the graphic narrative’s ability to present and withhold simultaneously. A panel might show a character’s face in shadow, suggesting depths of experience while acknowledging the limits of representation.

The visual testimony of graphic narratives often manifests through repetition and variation. A traumatic image might appear across multiple panels, each iteration slightly different, creating a sense of memory’s unstable nature. This technique appears in works like Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, where certain images—bombs falling, faces of the disappeared—return throughout the narrative like haunting refrains. The graphic narrative becomes a form of visual archaeology, excavating buried memories and presenting them as fragments rather than complete reconstructions.

The power of visual testimony lies in its ability to bypass language’s inadequacies. When words fail to capture the full weight of experience, images step forward to bear witness. Yet these images do not claim to represent trauma completely—they acknowledge their own limitations, creating space for readers to fill in what cannot be shown. This collaborative aspect of meaning-making between creator and reader mirrors the way trauma survivors often need others to help them piece together their experiences.

| Trauma Theory Element | Application | Visual Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal disruption | Non-linear panel sequences | Fragmented timelines |

| Repetition compulsion | Recurring visual motifs | Echoing images |

| Dissociation | Separated text and image | Disconnected elements |

| Witnessing | Reader as co-creator | Interpretive gaps |

| Unspeakability | Visual metaphor | Symbolic representation |

2. Graphic Narrative and the Gutter Between Pain

The gutter—that white space between panels—serves as the graphic narrative’s most powerful tool for containing the uncontainable. Comics theorist Scott McCloud identified the gutter as the space where reader imagination transforms two static images into a flowing narrative. In trauma narratives, however, the gutter becomes something more profound: a repository for experiences too overwhelming to be directly represented. It is where the unspeakable lives, where pain finds refuge in absence rather than presence.

The graphic narrative’s relationship with gutters creates a unique form of reader participation. Unlike other storytelling techniques that guide readers through predetermined emotional landscapes, graphic narratives require readers to fill in the gaps. This collaborative act of meaning-making can be both powerful and challenging when dealing with traumatic content. Readers must actively engage with difficult material, constructing bridges between panels that may span years of suffering or moments of unbearable intensity.

The strategic use of gutter space allows graphic narratives to address trauma’s temporal complexity. Time moves differently in the aftermath of trauma—moments can stretch into eternities, while years can collapse into single, overwhelming instants. The gutter accommodates this distorted temporality by allowing creators to juxtapose moments from different time periods without explanation. A panel showing a child’s face might be followed by one showing the same person decades later, with the gutter containing all the unspoken years of processing and healing.

The emotional significance of gutter space frequently surpasses that of the panels themselves. What happens between the frames—the violence implied but not shown, the words spoken but not recorded, the healing that occurs in private moments—carries tremendous narrative force. This technique appears powerfully in works like Maus, where the most devastating revelations often occur in the spaces between panels, requiring readers to confront their own assumptions about what they think they know about historical trauma.

| Gutter Function | Trauma Application | Reader Experience |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal transition | Time distortion | Disorientation |

| Spatial separation | Emotional distance | Protective buffering |

| Narrative gap | Unspeakable content | Active interpretation |

| Rhythmic pause | Processing time | Reflective space |

| Conceptual bridge | Meaning construction | Collaborative creation |

3. Graphic Narrative as Fragmented Consciousness

The postmodern understanding of fragmentation finds its most literal expression in graphic narratives, where the very structure of the page mirrors the fractured nature of consciousness under duress. Traditional narrative forms impose a linear progression that can feel false when dealing with trauma, which rarely unfolds in neat, chronological sequences. Graphic narratives embrace fragmentation as both technique and theme, using broken panels, interrupted sequences, and non-linear layouts to reflect the mind’s response to overwhelming experience.

Postmodern fragmentation theory suggests that contemporary experience is characterized by discontinuity, multiplicity, and the breakdown of grand narratives. Graphic narratives embody these concepts through their formal properties. A single page might contain panels of different sizes, irregular shapes, and varying temporal relationships. This visual fragmentation mirrors the way traumatic memories often exist as isolated fragments rather than coherent stories. The mind under stress does not organize experience into neat categories—it preserves what it can and discards what it cannot process.

The layout of graphic narrative pages becomes a psychological map of trauma’s impact. Panels might shrink to claustrophobic squares when depicting moments of intense fear, or expand to full-page spreads when showing overwhelming emotions. Some panels might lack borders entirely, allowing their contents to bleed into neighboring spaces, suggesting the way trauma disrupts normal boundaries between past and present, self and other, safety and danger. These formal choices create reading experiences that mirror the disorientation of traumatic memory.

The fragmented consciousness depicted in graphic narratives often reflects broader social and political fragmentations. Individual trauma frequently connects to collective experiences of displacement, violence, oppression, or conflict. The broken panels and disrupted sequences that characterize these narratives acknowledge that personal healing cannot be separated from larger social healing. The form itself becomes a statement about the need to piece together not just individual stories, but entire communities’ experiences of loss and recovery.

| Fragmentation Element | Psychological Function | Narrative Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Irregular panel shapes | Distorted perception | Disorienting reading |

| Size variations | Emotional intensity | Rhythmic emphasis |

| Broken borders | Boundary dissolution | Bleeding content |

| Non-linear sequences | Memory disruption | Temporal confusion |

| Multiple perspectives | Fractured identity | Complex viewpoints |

4. Graphic Narrative and the Body in Stillness

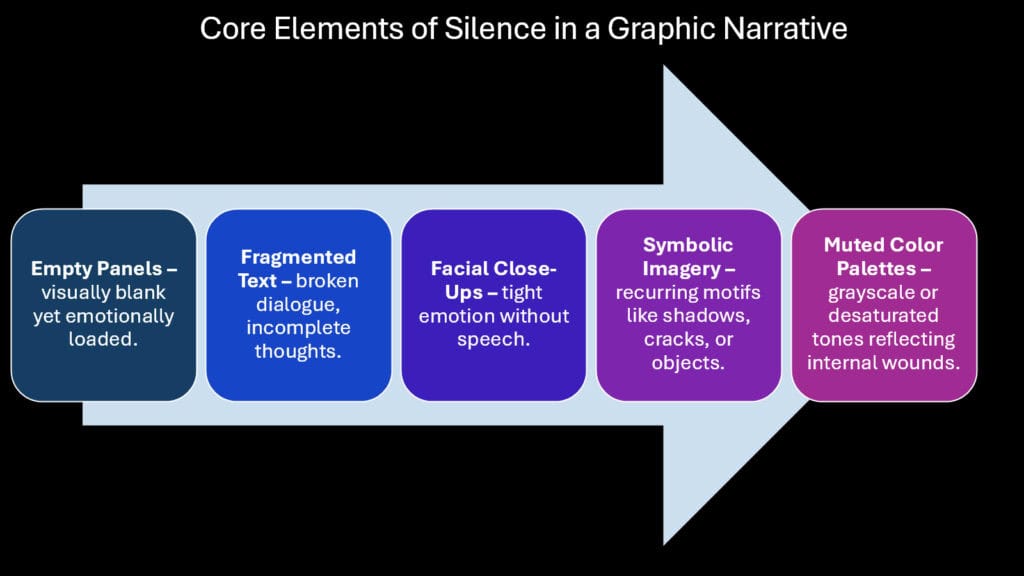

The graphic narrative’s relationship with stillness creates a unique space for trauma to be witnessed without being exploited. Unlike film or other moving media, graphic narratives exist in a state of permanent pause, allowing readers to spend as much time as needed with difficult images. This stillness serves multiple functions in trauma narratives: it provides safety for both creators and readers, it mirrors the frozen quality of traumatic memory, and it creates space for contemplation rather than consumption.

The body in graphic narratives often communicates what words cannot express. A character’s posture, the set of their shoulders, the way they hold their hands—these visual elements carry enormous emotional weight. Trauma frequently manifests through the body before it can be articulated through language. The graphics capture these physical manifestations of pain with particular effectiveness, freezing moments of bodily expression that might be missed in other media.

The stillness of graphic narratives allows for a different kind of witnessing than what is possible in dynamic media. Readers can return to particularly powerful images, studying them for details that might have been missed on first viewing. This capacity for extended contemplation creates opportunities for deeper understanding and empathy. The frozen gesture becomes a meditation on suffering, inviting readers to sit with difficult emotions rather than rushing past them.

The interplay between stillness and movement in graphic narratives creates a unique temporal experience. While individual panels remain static, the sequence of panels creates movement through time and space. This combination allows creators to show both the frozen quality of traumatic moments and the slow process of healing and change. A character might appear identical across multiple panels, with only subtle changes in expression or posture indicating the passage of time and the gradual process of recovery.

| Stillness Element | Trauma Function | Reader Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Frozen gesture | Captured pain | Extended witness |

| Static expression | Emotional suspension | Contemplative viewing |

| Repeated poses | Temporal compression | Meditative effect |

| Unchanging backgrounds | Psychological stasis | Focused attention |

| Suspended action | Arrested development | Reflective pause |

5. Graphic Narrative as Visual Absence and Erasure

Roland Barthes’ semiotics provides a framework for understanding how graphic narratives create meaning through absence as much as presence. In Barthes’ terms, every image contains both denotative elements (what is literally shown) and connotative elements (what is suggested or implied). Graphic narratives dealing with trauma often derive their power from connotative absence—from what is deliberately not shown, not said, not resolved. These strategic omissions create spaces where readers must confront their own assumptions and fill in gaps with their own understanding.

The technique of visual erasure in graphic narratives serves multiple functions. It can protect survivors by not exposing them to explicit recreations of their trauma, while simultaneously acknowledging the reality of their experiences. A face might be shown only in shadow, suggesting the presence of a person while maintaining their anonymity. A traumatic event might be depicted through its aftermath rather than its occurrence, allowing readers to understand its impact without being subjected to its violence.

Empty word balloons represent one of the most powerful tools in the graphic narrative’s arsenal of absence. These hollow spaces acknowledge that some experiences resist language entirely. They suggest the presence of communication while admitting its impossibility. The empty balloon becomes a visual metaphor for the silence that often surrounds trauma, the words that cannot be spoken, the stories that cannot be told in conventional ways.

The strategic use of blurred or obscured images reflects the way memory itself functions in the aftermath of trauma. Details may be lost or distorted, faces may become unrecognizable, and events may blur together. Rather than trying to impose false clarity on these unclear memories, graphic narratives can embrace the uncertainty and partial knowledge that characterizes traumatic experience. This approach honors the reality of survivors’ experiences while acknowledging the limitations of any attempt to represent trauma fully.

| Absence Technique | Semiotic Function | Trauma Application |

|---|---|---|

| Obscured faces | Denotative protection | Survivor anonymity |

| Empty word balloons | Connotative silence | Unspeakable experience |

| Blurred images | Uncertain memory | Fragmented recall |

| Missing panels | Temporal gaps | Lost time |

| Void spaces | Emotional emptiness | Psychological numbing |

6. Graphic Narrative as a Private Witness for Collective Pain

The intimate format of the graphic narrative establishes a distinctive environment in which personal trauma can shed light on wider social and political realities. Unlike public memorials or historical documents, graphic narratives invite readers into private spaces where individual experiences of pain connect to collective histories of suffering. This intimate witnessing allows for a form of understanding that is both personal and political, individual and communal.

The graphic narrative’s ability to blend the private and public stems from its format’s inherent intimacy. Reading a graphic narrative is typically a solitary activity, creating a sense of private communion between the reader and the story. This intimacy allows for the kind of vulnerable sharing that might be difficult in more public forums. The reader observes individual suffering, yet this observation holds wider significance for comprehending shared trauma.

The visual language of graphic narratives often employs universal symbols and metaphors that allow individual stories to speak for broader experiences. A single figure walking through a devastated landscape might represent not just one person’s journey, but the experience of all refugees, all survivors, all those displaced by violence or oppression. Its combination of specific detail and universal symbol creates stories that are simultaneously personal and collective.

The format’s accessibility also contributes to its effectiveness as a vehicle for collective witness. Graphic narratives can reach audiences who might not engage with more academic or formal presentations of traumatic history. The combination of visual and textual elements creates multiple entry points for understanding, allowing readers with different learning styles and backgrounds to engage with difficult material. This accessibility serves the broader goal of creating shared understanding about collective trauma.

| Witness Function | Individual Level | Collective Level |

|---|---|---|

| Intimate sharing | Personal testimony | Community healing |

| Universal symbols | Specific experience | Shared understanding |

| Accessible format | Individual processing | Broader education |

| Visual metaphor | Personal meaning | Cultural significance |

| Empathetic connection | Private communion | Social solidarity |

Conclusion: Why the Graphic Narrative Hears What We Can’t Say

The graphic narrative succeeds where other forms might fail because it does not demand that trauma be translated into language that was never designed to hold such weight. Instead, it creates new languages—visual, spatial, temporal—that can accommodate the contradictions and complexities of traumatic experience. Through its unique combination of image and text, presence and absence, showing and withholding, the graphic narrative offers a form of witness that is both protective and revealing.

The six approaches explored in this article work together to create a storytelling medium that honors the full complexity of trauma while maintaining respect for those who have survived it. Visual testimony creates space for memory’s fragments without demanding false coherence. The space between the panels recognizes that certain experiences cannot be directly represented. Fragmented consciousness reflects the reality of minds under stress. Stillness allows for contemplation rather than consumption. Absence creates meaning through what is not shown. And private witness connects individual pain to collective understanding.

The graphic narrative’s power lies in its ability to hold contradictions without resolving them. It can be simultaneously universal and specific, intimate and political, present and absent. This capacity for contradiction mirrors trauma’s own contradictory nature—the way it can be both overwhelmingly present and impossibly distant, both deeply personal and broadly shared. The graphic narrative does not try to solve these contradictions but rather creates space for them to coexist.

As our understanding of trauma continues to evolve, the graphic narrative offers a format that can evolve with it. Its flexibility allows for new approaches to representing difficult experiences while maintaining the core commitment to witness and understanding. In a world where traditional narratives often fail to capture the complexity of contemporary experience, the graphic narrative provides a way forward—not through shouting, but through the kind of quiet listening that allows truth to emerge in its own time and its own way.

| Graphic Narrative Strength | Traditional Narrative Limitation | Unique Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Visual-textual synthesis | Language-dependent | Multi-modal expression |

| Spatial flexibility | Linear progression | Non-linear exploration |

| Reader participation | Passive consumption | Active meaning-making |

| Fragmented structure | Imposed coherence | Authentic complexity |

| Contemplative stillness | Temporal pressure | Reflective witnessing |