Table of Contents

Introduction: How the Unreliable Narrator Warps the Story-world

Picture this: you trust someone completely, only to discover they’ve been weaving lies into every conversation. That unsettling feeling mirrors what happens when readers encounter an Unreliable Narrator. This storytelling technique doesn’t just present false information—it fundamentally alters how we perceive reality within a narrative.

The Unreliable Narrator stands as one of literature’s most powerful and frequently employed devices. Writers across cultures have wielded this technique to challenge readers’ assumptions and create stories that linger long after the final page. From Akutagawa’s conflicting testimonies in “In a Grove” to the delusional perspectives in Nabokov’s “Lolita,” these unreliable narrators force us to question everything we think we know.

What makes the Unreliable Narrator so compelling is its ability to mirror our own flawed perceptions. Just as we filter experiences through personal biases and incomplete memories, these narrators present distorted versions of truth. They don’t simply lie—they reveal how subjective all storytelling really is.

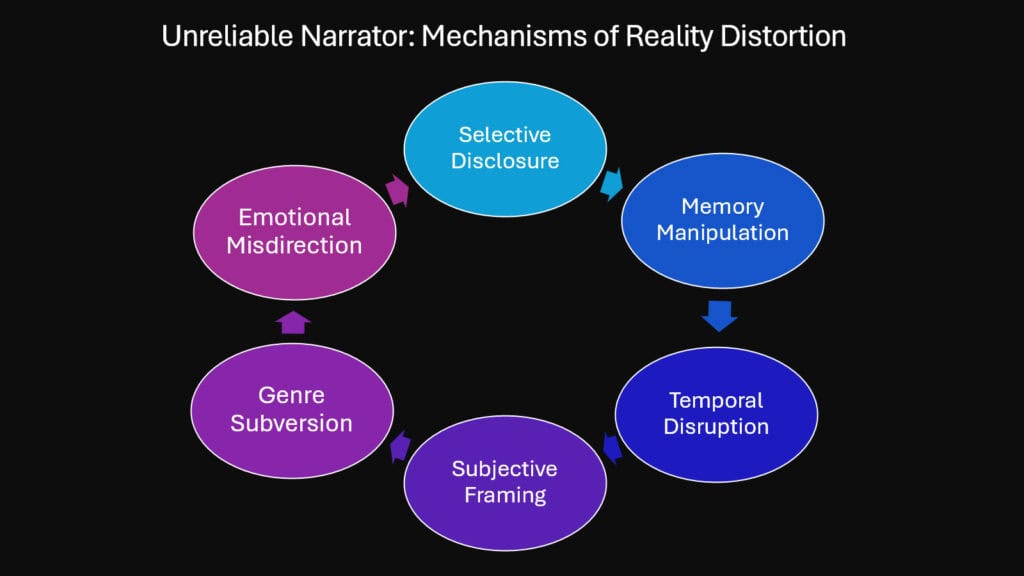

This narrative technique operates through six distinct mechanisms that fracture conventional storytelling. These methods range from manipulating temporal structure to exploiting reader psychology. Each approach demonstrates how the Unreliable Narrator doesn’t just tell false stories—it breaks the very foundations of narrative reality.

The power of this technique extends beyond mere deception. It creates stories where truth becomes negotiable, where facts bend to perspective, and where readers must actively participate in constructing meaning. These narrators don’t just unreliable—they’re revolutionary.

Understanding how Unreliable Narrators function reveals something profound about storytelling itself. They show us that every narrative is subjective, every perspective limited, and every truth partial. In doing so, they create some of literature’s most haunting and memorable experiences.

| Traditional Narrative Elements | How Unreliable Narrators Distort Them |

|---|---|

| Linear chronology | Fragmented or non-linear time sequences |

| Objective facts | Subjective interpretations presented as truth |

| Clear cause and effect | Ambiguous or manipulated causal relationships |

| Reliable exposition | Information filtered through bias or delusion |

| Consistent character portrayal | Shifting or contradictory characterizations |

1. The Unreliable Narrator as the Master of False Beginnings

The concept of In Medias Res traditionally plunges readers into the middle of action, but Unreliable Narrators twist this technique into something far more sinister. They don’t just start in the middle of events—they begin in the middle of deceptions. This creates an immediate disorientation that colors everything that follows.

Japanese literature offers another striking example in Kobo Abe’s “The Woman in the Dunes.” The narrator presents his predicament matter-of-factly, as if his entrapment is simply another life experience. This false beginning disguises the horror of his situation behind mundane observations and rational explanations.

The power of false beginnings lies in their ability to establish trust before betraying it. Unreliable Narrators often present themselves as reasonable, articulate voices that readers naturally want to believe. They create an illusion of honesty through detailed observations and seemingly candid admissions.

Russian literature demonstrates this technique masterfully in Dostoevsky’s “Notes from Underground.” The narrator immediately declares himself a spiteful man, yet this apparent honesty becomes its own form of manipulation. His self-deprecation serves to disarm readers while concealing deeper layers of self-deception.

These false beginnings don’t just mislead—they actively shape how readers interpret subsequent events. Once we accept the narrator’s initial framework, we unconsciously filter new information through their distorted lens. This makes later revelations all the more shocking when the foundation crumbles.

| In Medias Res Technique | Traditional Use | Unreliable Narrator’s Distortion |

|---|---|---|

| Opening with action | Creates immediate engagement | Creates immediate deception |

| Establishing urgency | Builds narrative tension | Builds false trust |

| Providing context later | Reveals background gradually | Reveals lies gradually |

| Setting tone | Establishes genre expectations | Establishes false reality |

| Character introduction | Shows protagonists in crisis | Shows narrators as victims |

2. The Unreliable Narrator and the Illusion of Emotional Honesty

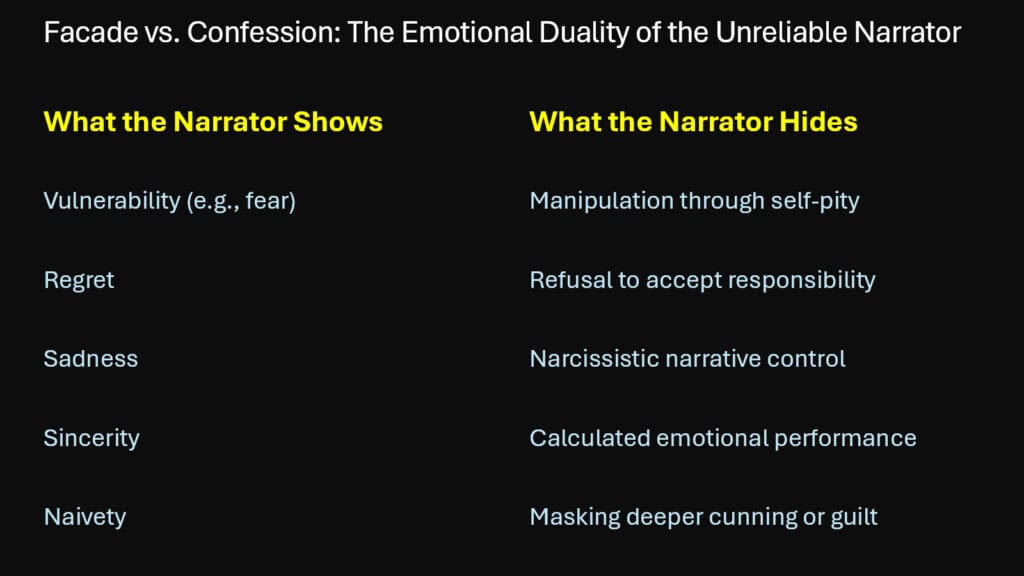

Emotional vulnerability creates powerful connections between narrators and readers. Unreliable Narrators exploit this psychological principle by offering selective confessions that feel deeply personal while concealing crucial truths. Their emotional honesty becomes a smokescreen for factual deception.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie explores this dynamic in “Purple Hibiscus,” where the young narrator Kambili’s innocent perspective initially masks the full horror of her family’s dysfunction. Her emotional truth—the fear, confusion, and love she feels—remains genuine even as her understanding of events proves incomplete. This partial honesty makes her eventual revelations more devastating.

Latin American literature provides another compelling example in Laura Esquivel’s “Like Water for Chocolate.” Tita’s passionate narration feels emotionally authentic, yet her magical realist perspective blurs the line between metaphor and reality. Her feelings are real, but her interpretation of cause and effect becomes questionable.

The technique works because emotional truth often feels more authentic than factual accuracy. When narrators share their deepest fears, regrets, or desires, readers instinctively empathize. This emotional connection creates a blind spot that Unreliable Narrators ruthlessly exploit.

Consider how Ian McEwan’s Briony in “Atonement” shares her guilt and shame with brutal honesty. Her emotional journey feels genuine and compelling, which makes her manipulation of facts all the more shocking. She uses her pain as currency to purchase reader sympathy while concealing her active role in creating that pain.

Australian literature offers another perspective in Tim Winton’s works, where narrators often share childhood traumas with raw honesty. Yet their adult interpretations of these events may be colored by years of rationalization and self-justification. The emotional scars are real, but the explanations become suspect.

| Emotional Honesty Elements | Reader Response | Narrative Function |

|---|---|---|

| Vulnerability and confession | Increased empathy | Builds false trust |

| Shared trauma or pain | Protective instincts | Deflects suspicion |

| Self-doubt and uncertainty | Perception of authenticity | Masks deliberate deception |

| Intense feelings | Emotional investment | Creates reader bias |

| Personal revelations | Sense of intimacy | Facilitates manipulation |

3. The Unreliable Narrator and Memory Distortion in Narrative Time

Stream of Consciousness technique traditionally captures the natural flow of human thought, but Unreliable Narrators weaponize this narrative style to present distorted memories as authentic experiences. Their consciousness becomes a funhouse mirror reflecting fractured versions of reality.

Haruki Murakami’s narrators exemplify this approach, particularly in “Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World.” The protagonist’s memories feel genuine and detailed, yet they’re literally manufactured by external forces. The Stream of Consciousness style makes these artificial memories feel as real as authentic experiences.

Virginia Woolf pioneered this technique in “Mrs. Dalloway,” where Clarissa’s consciousness flows between past and present. While Woolf’s narrator remains reliable, later writers learned to corrupt this technique. The natural wandering of memory becomes a perfect vehicle for introducing false or distorted recollections.

The strength of memory distortion is rooted in its psychological authenticity. Real memories often feel fragmented, emotionally charged, and subjectively colored. Unreliable Narrators exploit this by presenting fabricated memories that feel more “real” than actual events might.

Chinese literature demonstrates this in Mo Yan’s “Red Sorghum,” where the narrator presents family legends as personal memories. The Stream of Consciousness technique blurs the line between inherited stories and lived experiences, creating a narrative where truth becomes collectively constructed rather than individually witnessed.

Memory’s natural unreliability provides perfect cover for narrative deception. Since readers accept that memory can be flawed, they’re more likely to trust narrators who acknowledge their limitations while secretly exploiting them.

| Stream of Consciousness Elements | Traditional Function | Unreliable Narrator’s Manipulation |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal fluidity | Shows natural thought patterns | Disguises chronological deception |

| Associative leaps | Reveals character psychology | Introduces false connections |

| Emotional intensity | Creates intimate reader experience | Overwhelms rational analysis |

| Fragmented structure | Mirrors actual consciousness | Hides logical inconsistencies |

| Sensory details | Enhances realism | Makes false memories convincing |

4. The Unreliable Narrator as a Manipulative Architect of Plot Twists

Some Unreliable Narrators transcend mere confusion or self-deception to become conscious architects of narrative surprise. These calculating storytellers deliberately plant false clues, misdirect reader attention, and engineer revelations that reframe everything that came before.

Agatha Christie’s “The Murder of Roger Ackroyd” revolutionized detective fiction by making the narrator himself the murderer. Dr. Sheppard carefully omits crucial information while appearing to provide complete accounts. His manipulation is so subtle that readers only recognize it in retrospect, when Christie reveals the careful architecture of deception.

Korean literature offers another sophisticated example in Kim Young-ha’s “I Have the Right to Destroy Myself.” The narrator presents himself as a passive observer of others’ destructive behaviors, yet gradually reveals his active role in orchestrating these tragedies. His apparent detachment masks deliberate manipulation.

These narrators function as literary magicians, directing reader attention away from crucial elements while appearing transparent. They understand that successful deception requires not just lies but strategic truth-telling that supports their false narrative.

African literature provides compelling examples in Chinua Achebe’s “Things Fall Apart,” where Okonkwo’s perspective shapes how readers initially view colonialism and cultural change. While not deliberately deceptive, his limited viewpoint creates blind spots that later revelations expose.

The creation of plot twists necessitates that narrators possess a profound understanding of reader psychology. They must anticipate how audiences will interpret information, then craft revelations that exploit these assumptions. This makes them active collaborators in their own story’s construction.

Russian literature demonstrates this in Nikolai Gogol’s “The Overcoat,” where the narrator’s seemingly sympathetic portrayal of Akaky Akakievich gradually reveals itself as subtly mocking. The apparent compassion masks a more complex attitude that only becomes clear through careful rereading.

| Plot Engineering Techniques | Purpose | Reader Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic omission | Hide crucial information | Creates false confidence |

| Red herring details | Misdirect attention | Builds wrong assumptions |

| Selective revelation | Control information flow | Manipulates emotional response |

| False emphasis | Highlight unimportant elements | Obscures real significance |

| Gradual disclosure | Build false narrative foundation | Makes revelations more shocking |

5. The Unreliable Narrator as a Mirror of Reader Bias

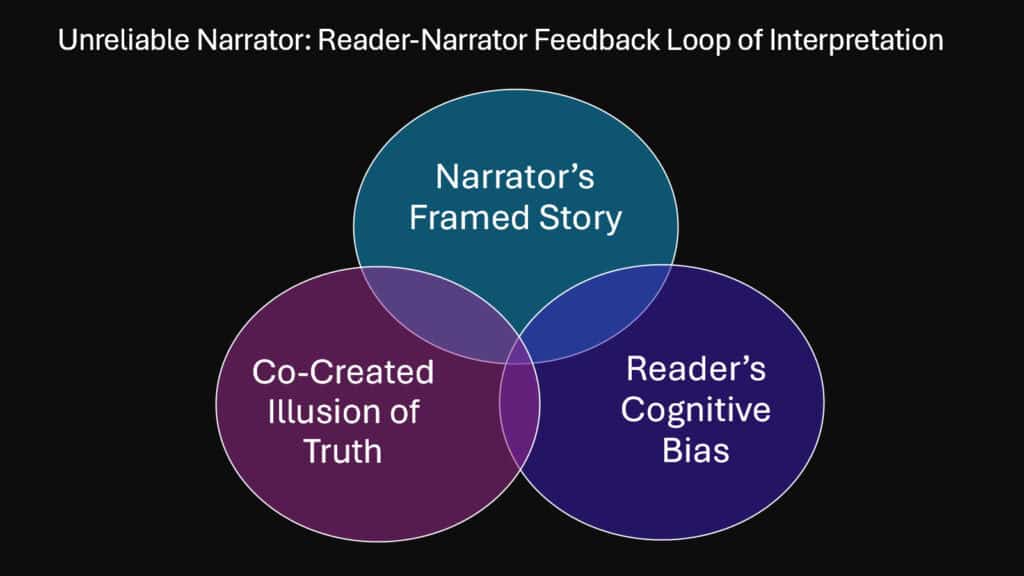

Reader-Response Theory suggests that meaning emerges from the interaction between text and reader, but Unreliable Narrators exploit this collaborative process by feeding audiences exactly what they want to believe. They transform readers from passive recipients into active accomplices in narrative deception.

Nabokov’s “Lolita” provides perhaps the most disturbing example of this technique. Humbert Humbert’s eloquent, cultured voice appeals to readers’ literary sensibilities while describing horrific acts. His sophisticated language and cultural references create a false intimacy that some readers find seductive, despite the moral horror of his actions.

European literature offers another perspective in Kazuo Ishiguro’s “The Remains of the Day.” Stevens the butler presents himself as the epitome of professional dignity, appealing to readers’ respect for duty and service. Yet his apparent nobility masks willful blindness to his employer’s Nazi sympathies and his own emotional cowardice.

These narrators succeed by identifying what readers want to believe about themselves and their world. They offer flattering mirrors that reflect audience prejudices and desires back in appealing forms. This psychological manipulation proves far more effective than simple lies.

South Korean cinema and literature demonstrate this in works like “Parasite,” where class perspectives shape how audiences initially sympathize with different characters. The narrative deliberately plays with viewer biases about poverty, wealth, and moral responsibility.

Reader-Response Theory reveals how audiences actively construct meaning from textual cues. Unreliable Narrators weaponize this process by providing cues that encourage specific interpretations while concealing alternative readings. They involve readers in their own deception.

The mirror effect becomes particularly powerful when narrators embody reader fantasies or fears. They present exaggerated versions of audience desires—sophistication, victimhood, moral superiority—that feel too appealing to question critically.

| Reader-Response Elements | Traditional Function | Unreliable Narrator’s Exploitation |

|---|---|---|

| Active interpretation | Creates personal meaning | Encourages biased reading |

| Gap-filling | Completes narrative understanding | Introduces false assumptions |

| Emotional identification | Builds character connection | Creates protective blindness |

| Cultural recognition | Establishes common ground | Exploits shared prejudices |

| Value projection | Finds personal relevance | Manipulates moral judgment |

6. The Unreliable Narrator and Genre-Bending Reality Loops

When narrative genres blur and overlap, Unreliable Narrators find their most fertile ground. These boundary-crossing stories create spaces where normal rules don’t apply, allowing narrators to manipulate not just facts but the very logic that governs their fictional worlds.

Jorge Luis Borges mastered this technique in stories like “The Garden of Forking Paths,” where the narrator exists simultaneously in multiple realities. The story operates as detective fiction, philosophical meditation, and metafictional experiment, creating a space where traditional narrative rules become meaningless.

Japanese literature offers another striking example in Kobo Abe’s “The Face of Another,” where psychological realism gradually shifts into surreal territory. The narrator’s transformation through plastic surgery becomes both literal medical procedure and metaphysical identity crisis, blurring the line between external change and internal dissolution.

Genre-bending allows Unreliable Narrators to exploit reader expectations about how different types of stories should work. A mystery creates certain assumptions about clues and solutions, while horror establishes different rules about cause and effect. Narrators who operate between genres can violate these expectations without appearing to break narrative logic.

Contemporary African literature demonstrates this in works like Amos Tutuola’s “The Palm-Wine Drinkard,” where folktale logic intersects with modern narrative techniques. The narrator’s journey operates simultaneously as spiritual quest, adventure story, and cultural preservation, creating a reality where impossible events feel perfectly natural.

These reality loops often emerge when narrators exist in multiple fictional frameworks simultaneously. They might be both detective and suspect, both victim and perpetrator, both human and something else entirely. This multiplicity generates recursive narratives in which cause and effect become circular.

The power of genre-bending lies in its ability to make the impossible feel inevitable. When story logic itself becomes unreliable, readers lose their anchor points for distinguishing truth from fiction, reality from delusion.

| Genre-Bending Elements | Traditional Boundaries | Unreliable Narrator’s Disruption |

|---|---|---|

| Mystery conventions | Clear clues and solutions | Contradictory evidence patterns |

| Realist expectations | Consistent cause and effect | Impossible events treated normally |

| Horror logic | Supernatural follows rules | Rules change mid-narrative |

| Fantasy frameworks | Magic has limitations | Limitations prove illusory |

| Historical accuracy | Facts remain constant | Facts shift with perspective |

Conclusion: Why the Unreliable Narrator Feels More Real Than Truth

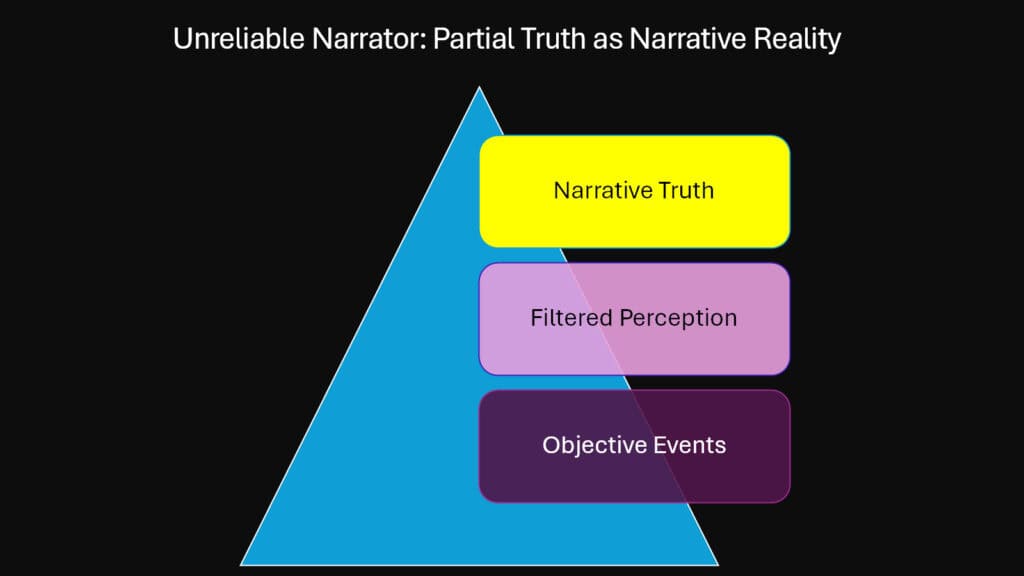

The Unreliable Narrator endures across cultures and centuries because it captures something essential about human experience. We all live inside partial truths, filtered through personal biases, incomplete memories, and self-serving interpretations. These narrators don’t just tell lies—they reveal how all perspective is inherently subjective.

The six techniques explored here demonstrate how Unreliable Narrators operate at every level of storytelling. They manipulate beginnings to establish false foundations, exploit emotional connections to build trust, corrupt memory to distort chronology, engineer surprises to control revelation, mirror reader biases to ensure complicity, and bend genre rules to escape logical constraints.

What makes these techniques so powerful is their basis in psychological reality. Authentic memory can be inconsistent, genuine emotions can obscure judgment, true perspective is constrained, and actual truth is frequently subjective. Unreliable Narrators simply exaggerate tendencies that already exist in human consciousness.

The global examples examined here reveal how different cultures have embraced this technique while adapting it to local concerns. Whether addressing historical trauma, social inequality, personal identity, or metaphysical questions, writers worldwide have found the Unreliable Narrator an invaluable tool for exploring complex truths.

In our contemporary world of competing narratives and alternative facts, the Unreliable Narrator feels more relevant than ever. These fictional voices prepare us for a reality where truth itself has become contested territory. They teach us to question not just what we’re told, but how our own biases shape what we’re willing to believe.

Perhaps the most unsettling aspect of Unreliable Narrators is how familiar they feel. Their voices echo our own internal monologues—self-justifying, selective, emotionally driven, and absolutely convinced of their own authenticity. In recognizing their deceptions, we glimpse the possibility of our own.

The enduring power of this technique lies in its fundamental honesty about dishonesty. By showing us how easily truth can be manipulated, Unreliable Narrators paradoxically reveal deeper truths about the nature of consciousness, memory, and human relationship to reality itself.

| Narrative Truth Types | Reliability Level | Reader Recognition |

|---|---|---|

| Factual accuracy | Completely unreliable | Often obvious |

| Emotional authenticity | Partially reliable | Difficult to detect |

| Psychological insight | Sometimes reliable | Requires careful analysis |

| Cultural perspective | Culturally relative | Depends on reader background |

| Philosophical implications | Ultimately reliable | Only clear in retrospect |